On the morning of August 9, authorities found Moumita Debnath, a trainee doctor at R. G. Kar Medical College in Kolkata, India, dead in a seminar room on campus. The previous night, she had dinner with her colleagues and then retired in a seminar hall after a 36-hour shift in the hospital. College authorities initially informed her family that she had committed suicide. However, the semi-nude state in which they discovered her, with her eyes, mouth, and genitals bleeding, highlighted a disturbing aspect of rape culture in India. The autopsy report later confirmed this suspicion: someone had raped and sexually assaulted Moumita before murdering her.

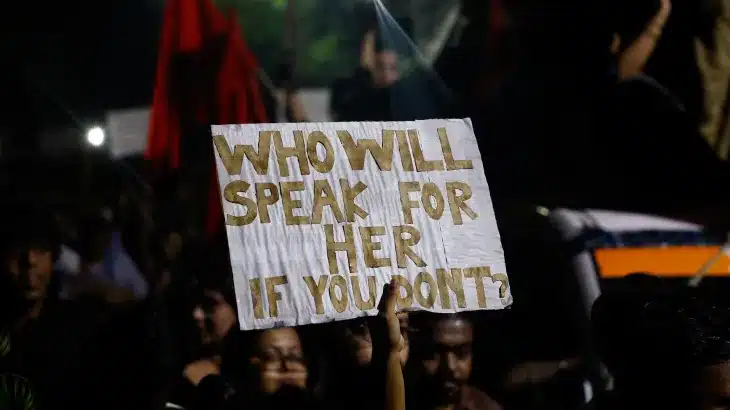

The incident has since brought into focus the safety of women and doctors in India. It has sparked considerable outrage and nationwide protests. More importantly, it has established itself as a microcosm of a severe and pervasive issue in the country: sexual violence.

The Rape Culture in India: Statistics and Trends

Rape happens to be the fourth most common crime against women in India. The 2021 annual report of the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) revealed that authorities registered 31,677 rape cases across the country, averaging 86 cases per day and marking an increase from 28,046 cases in 2020. Perpetrators known to the victim committed 28,147 (almost 89%) of these 31,677 rape cases. Furthermore, 10% of the victims were minors or below 18 years of age, which is the legal age of consent.

Thus, like many cases preceding it, Moumita’s case demonstrates a deeply entrenched rape culture in India. This culture encompasses societal norms and practices that trivialize, normalize, or excuse sexual violence and harassment. A complex interplay of historical legacies, cultural norms, and systemic failures influences this culture, making India one of the countries with the lowest per capita rates of rape. Therefore, understanding the pervasive nature of rape culture in India requires examining its historical underpinnings and how these influences have permeated societal norms and legal systems.

![Protestors demonstrate against rape culture in India [Reuters]](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/60555372_605.webp)

History, Society, and Culture

The historical roots of rape culture in India originate from the British colonial era and the traditional patriarchal norms that have long governed Indian society. Starting in the 18th century, colonial rulers implemented legal systems heavily influenced by Victorian morality. This moral framework placed a high value on women’s honor and reputation, deeply influencing British legal principles of the time. Lawmakers formulated laws to preserve social order and protect family honor. They often viewed women primarily in terms of their sexual purity and social worth.

The Indian Penal Code

As a matter of fact, the Indian Penal Code (IPC) of 1860, drafted by Thomas Babington Macaulay, is one of the most enduring legacies of British rule. While the IPC codified laws in India, colonial authorities shaped its approach to sexual violence by prioritizing the protection of women’s chastity over their autonomy. This code primarily viewed rape as an offense against a woman’s honor and, by extension, her male guardians. It did not recognize rape as a violation of a woman’s bodily integrity and personal agency. This perspective laid the groundwork for a legal framework that, even after independence, struggled to fully recognize and address the complexities of sexual violence.

![Thomas Babington Macaulay who introduced English and western concepts to education in India [Getty Images]](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Thomas-Babington-Macaulay.webp)

Traditional Norms: Patriarchy and Women’s Subordination

Traditional Indian norms, deeply rooted in religious and cultural practices, have reinforced patriarchal values. These values position women as subordinate to men, viewing them as the property of their male relatives. This framework ties a woman’s virtue closely to her family’s honor and dictates that her male relatives must guard her sexuality. As a result, society primarily views women through the lens of their relationship with men, rather than recognizing them as autonomous individuals.

Systemic Gender Inequality and Its Manifestations in India

Systemic gender inequality in the country manifests in various forms, including dowry, female infanticide, and child marriage. These practices not only reflect the low value society places on women but also lay the foundation for normalizing violence against them.

Dowry System: A Cultural Legacy of Violence Against Women

For example, the dowry system, although officially illegal, continues to thrive in many parts of India, leading to violence against women who are unable to meet dowry demands.

Case Study: Nidhi’s Tragic Story

Authorities found 31-year-old Nidhi dead in her home in the early hours of August 24 in Greater Noida’s Jaganpur village. This incident marks the most recently reported case in this regard. Upon arrival at the scene, the police discovered Nidhi lying in a pool of blood with a bullet wound to her neck. Her father, Chaudhary Harveer Singh, who reported the crime, revealed a history of dowry harassment by her husband and in-laws. According to an officer investigating the case, Nidhi left home multiple times due to the abuse but always returned. Tragically, someone cut her life so brutally short. In the larger scheme of things, this grueling act has emerged as a consequence of deep-rooted cultural norms that view women as commodities. It serves as a stark reminder of the continued impact of the dowry system on women’s lives in India.

![Image of Dowry at the wedding of the Imam of Delhi [Wikimedia Commons]](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/1200px-India_-_Delhi_wedding_-_5438.webp)

The Pervasiveness of Dowry-Related Violence

Various research studies and reports show that dowry-related violence often links to domestic abuse. Society and law enforcement frequently overlook or inadequately address this issue. In this case, as in many others similar to it, the perpetrators initially evaded significant consequences. This evasion occurred due to the pervasive nature of dowry-related violence and the societal norms that often condone and protect such practices.

Female Infanticide and Gender-Selective Abortions

Similarly, female infanticide and gender-selective abortions continue to be a grave issue. The Haryana and Punjab regions in India have seen alarming rates of female infanticide due to a strong cultural preference for sons. Reports indicate that the sex ratio in these areas is skewed due to the illegal practice of sex-selective abortion, reflecting the low value placed on female children.

Child Marriage: A Continuing Challenge

Child marriage is another prevalent practice despite legal prohibitions. The Rajasthan region, for instance, has high rates of child marriages, often justified by traditional norms. The devaluation of women, rooted in these cultural practices, not only undermines women’s education and autonomy but also creates an environment where sexual violence is more likely to occur and less likely to be condemned.

![Students performing a play named "Child Marriage" [UNICEF]](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Student-perfoming-play-named-child-marriage-1.JPG.webp)

Honor, Shame, and the Stigmatization of Survivors of Sexual Violence

This systemic devaluation, in turn, intertwines with broader cultural factors, such as the concept of honor (izzat) and shame (sharam), which significantly influence how sexual violence is perceived and addressed in Indian society.

In this context, honor is often tied to the control of women’s sexuality, and a woman’s “purity” is seen as a reflection of her family’s societal reputation. Consequently, survivors of rape and sexual violence are frequently stigmatized, blamed, and ostracized rather than supported. As a matter of fact, this stigmatization discourages many survivors from reporting sexual violence, fearing social repercussions more than the violence itself.

Nirbhaya Case: A National Reflection on Honor and Sexual Violence

Even in the aftermath of the horrific 2012 Nirbhaya gang rape, the discussion around her “honor” and “purity” was pervasive. Some even questioned her decision to be out late at night. Her family’s societal reputation was also a significant concern. This underscores how deeply ingrained notions of honor and shame impact the perception of sexual violence in India.

Legal Reforms and the Evolution of Laws on Sexual Violence

Cumulatively, all of these factors highlight societal attitudes that normalize control over women’s bodies. They also contribute to the acceptance of sexual violence. This acceptance is evidenced by the sluggish and often inadequate evolution of laws related to sexual violence in India.

The 2013 Criminal Law (Amendment) Act

The original provisions of the IPC regarding rape remained largely unchanged for over a century.

Significant legal reforms were not introduced until after the aforementioned Nirbhaya gang rape. These reforms came through the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act of 2013. This Act broadened the definition of rape to include various forms of non-consensual sexual acts. It established stricter punishments for perpetrators and introduced provisions for expedited trials in cases of sexual violence.

Although it expanded the scope of offenses related to sexual violence, including acid attacks and stalking, significant gaps still remain. For instance, marital rape is still not criminalized in India, reflecting the continued influence of patriarchal values that prioritize the sanctity of marriage over women’s rights.

Media and Rape Culture in India

As unfortunate as it is, the cultural and social norms that significantly influence how sexual violence is perceived and addressed are often mirrored and reinforced in media representations.

The media—ranging from Bollywood films to news outlets and social media platforms—plays a crucial role in reflecting and shaping societal attitudes. Unfortunately, much of the media in India has historically contributed to the normalization of rape culture. It often fortifies misogynistic mindsets and fails to address the root causes of sexual violence. Analyzing media portrayals helps us understand how these entrenched societal attitudes are reinforced and normalized through popular culture.

The Bollywood and The Portrayals of Women

Most prominently, Bollywood, India’s influential film industry, has long been criticized for its problematic portrayal of women. This portrayal plays a significant role in emboldening rape culture.

The glamorization of stalking, harassment, and non-consensual romantic advances is a recurring theme in Bollywood. This glamorization blurs the lines between acceptable and unacceptable conduct, depicting such behaviors as acceptable or even desirable forms of courtship.

Case Study: Animal and Kabir Singh

For instance, the film Animal, released last year, enjoyed considerable success despite its troubling depiction of male aggression and toxic masculinity. The movie presents the male lead’s violent and possessive behavior as a form of love. This portrayal normalizes harmful attitudes toward relationships and gender dynamics.

Similarly, the movie Kabir Singh became the second highest-grossing Bollywood film of 2019. It faced criticism for portraying male leads who persistently pursue women despite initial rejections. The film frames this persistence as a romantic gesture rather than harassment. Such portrayals send dangerous messages to audiences, particularly young men. They suggest that controlling or coercive behavior is not only acceptable but also an expression of passionate love.

Moreover, item songs are musical numbers in Bollywood films that feature provocative dance sequences and objectify women. These songs further contribute to the normalization of rape culture. They often depict women as objects of male desire, reinforcing stereotypes that reduce women to mere commodities for male pleasure. Given the sexually suggestive content of item songs and their widespread popularity, they can perpetuate harmful attitudes. They desensitize viewers to the seriousness of sexual violence, thereby contributing to a broader culture that trivializes harassment and assault.

![Poster of movie "Kabir SIngh" [Twitter]](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/kabir-singh-twitter.webp)

News Media’s Role in Shaping Public Perception

Disappointingly, news media’s approach further compounds Bollywood’s portrayal of women, significantly shaping public discourse on sexual violence.

Indian news media often sensationalizes the coverage of rape cases, focusing on the lurid details of the crime rather than addressing the systemic issues that enable such violence.

For example, the 2012 Nirbhaya gang rape case received extensive media coverage, but much of it emphasized the brutality of the attack rather than the broader societal conditions that allowed it to happen.

Similarly, in the Unnao and Kathua cases, media coverage often focused on the political and communal aspects, overshadowing the gravity of the crimes and the suffering of the victims. This sensationalism can lead to a temporary public outcry, but it rarely translates into sustained pressure for meaningful societal or legal reforms. Moreover, by focusing primarily on extreme cases, the media often overlooks the more pervasive, everyday instances of sexual harassment and assault that countless women in India experience, thus failing to address the full scope of the issue.

![Protest for the Kathua and Unnao rape cases [Wikimedia Commons]](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/1280px-Protests_for_the_Kathua_Unnao_Rape_cases.webp)

Social Media: A Double-Edged Sword

In stark contrast with mainstream media, though, social media has emerged as a powerful tool in both challenging and perpetuating rape culture. On one hand, platforms like Twitter and Facebook have given voice to survivors and activists, enabling movements like #MeToo to gain traction in India. The case of journalist Priya Ramani, who accused former minister M.J. Akbar of sexual harassment, is a prominent example. Social media widely shared Ramani’s allegations, sparking widespread support and eventually leading to a landmark court case in which the court dismissed Akbar’s defamation suit against her. This dismissal marked a significant victory for the #MeToo movement in India. Notably, this case emerged as a powerful example of how activists can use social media to raise awareness, mobilize public opinion, and hold powerful figures accountable.

Yet, the same platforms that amplify survivors’ voices can also perpetuate rape culture through online harassment, trolling, and victim-blaming. Survivors who speak out about their experiences often face brutal backlash. This backlash includes threats of violence, character assassination, and attempts to discredit their stories.

For example, during the #MeToo movement in India, several women who came forward with allegations of sexual harassment faced intense online abuse. Many were accused of seeking attention or fabricating their stories for personal gain.

This online abuse reflects and reinforces the same misogynistic attitudes that underpin rape culture in the offline world. It creates a hostile environment for those seeking justice and accountability.

Institutional Responses

While media representation significantly influences societal attitudes toward sexual violence, the role of institutions is equally critical. Institutions can either perpetuate or combat rape culture. The responses of institutions—including the police, judiciary, educational establishments, and government—play a pivotal role. These responses shape how society addresses incidents of sexual violence. Unfortunately, in India, these institutions frequently fall short, reflecting and reinforcing the broader societal issues that underpin rape culture.

Police and Judicial Failures in Addressing Sexual Violence

Critics have widely condemned the police and judicial system in the country for their handling of sexual violence cases. They point out that systemic inefficiencies often compound deeply ingrained patriarchal attitudes. A glaring example is the Bilkis Bano case, in which it took nearly 17 years for authorities to serve justice after someone gang-raped her during the 2002 Gujarat riots. The initial police response was dismissive, with officers refusing to register her complaint. This case brought to light a broader pattern within law enforcement. Corruption, lack of sensitivity training, and inherent biases lead to mishandled investigations and low conviction rates.

To make matters worse, a particularly troubling trend has emerged in recent years: authorities have released convicted rapists early or even celebrated them upon their release. For instance, in the Bilkis Bano case, authorities prematurely released 11 convicts in 2022, and some celebrated their release with garlands, sparking outrage and raising serious concerns about the judicial system’s commitment to justice for survivors.

The Role of Educational Institutions in Rape Culture

Furthermore, educational institutions, universities, and schools in India also play a critical role in either challenging or encouraging rape culture.

These institutions are often where young people first encounter discussions about gender and sexuality. However, they frequently fail to provide safe environments for these conversations. In particular, the 2018 protests at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) against the mishandling of sexual harassment cases underscore systemic issues within educational institutions. The university’s reluctance to take decisive action against the accused reflects a broader trend. This trend shows that institutions prioritize their reputation over student safety. Many schools and universities in India lack comprehensive policies to address sexual violence. Additionally, the absence of sex education exacerbates the problem by leaving students ill-equipped to understand and respect concepts of consent.

![Student Protest at Jawaharlal Nehru University [Aljazeera]](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/90a52880a7f74039ac84191f4df08c7d_18.webp)

Government Policies and Legislative Reforms on Sexual Violence

Lastly, government policies and reforms serve as a vital component in shaping institutional responses to sexual violence. Although the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act of 2013 established stricter penalties for sexual offenses, it also set up fast-track courts to expedite rape cases. However, inconsistent implementation and a lack of resources have undermined the effectiveness of these measures. For instance, fast-track courts often fail to deliver swift justice as intended due to procedural delays and bureaucratic inefficiencies. Similarly, while the Protection of Children from Sexual Offenses (POCSO) Act represents a significant step forward in safeguarding minors, inadequate training and resources for enforcers limit its success.

At this juncture, it is worth noting that institutions play a crucial role in addressing sexual violence. However, intersecting factors such as caste, class, and regional differences often influence their effectiveness. Therefore, to develop a more comprehensive approach to tackling rape culture, it is vital to understand how these factors impact institutional responses.

Intersectionality in Rape Culture

Rape culture in India deeply intertwines with intersections of caste, class, religion, and regional disparities, compounding the vulnerability of certain groups to sexual violence. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality offers a framework for understanding how overlapping forms of discrimination shape the experiences of sexual violence survivors, revealing the complex nature of these issues.

![Kimberle Crenshaw, who coined the term "Intersectionality", speaks during the New York Women's Foundation's "Celebrating Women" breakfast in New York City [Getty Images]](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/equality-kimberle-crenshaw.webp)

Caste-Based Discrimination and Dalit Women’s Vulnerability

To begin with, Dalit women, situated at the lowest end of the caste hierarchy, face disproportionately high risks of sexual violence. The 2020 Hathras case starkly illustrates this intersectional oppression. It involved the brutal gang rape of a 19-year-old Dalit woman by four upper-caste men in Hathras district, Uttar Pradesh. The initial refusal of the police to properly document and investigate the crime underscores the systemic discrimination that Dalit victims face. Additionally, the manner in which they handled her body after her death highlights significant barriers to justice. The compounded disadvantage of economic class further exacerbates this issue. Women from economically deprived backgrounds often lack access to necessary legal resources and support services.

![Demonstration over the rape of Dalit woman [European Pressphoto Agency]](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/114723004_mediaitem114723002.jpg.webp)

Communal Violence and Sexual Exploitation of Religious Minorities

Religious and ethnic minorities, on the other hand, encounter their own set of challenges related to sexual violence. The Partition of India in 1947, for instance, marked a period of mass displacement and communal violence that resulted in widespread sexual violence against women, particularly from minority communities. During this tumultuous time, tens of thousands of women were abducted, raped, and subjected to brutal violence. This historical trauma has had a lasting impact on the affected communities, influencing contemporary experiences of sexual violence and emphasizing the intersection of gender-based violence with historical injustices.

In more recent times, the 2002 Gujarat riots provide a glaring example of how perpetrators systematically targeted Muslim women in acts of sexual violence.

The earlier-mentioned Bilkis Bano case highlights how individuals employed sexual violence as a tool of communal aggression. The subsequent legal process was fraught with delays and political interference, reflecting the broader issue of sexual violence against marginalized communities. This issue of communal violence persisted with the 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots, where reports indicated targeted sexual violence against Muslim women, illustrating how gender-based oppression intersects with communal conflict.

![A Hindu mob waves swords at an opposing Muslim crowd during street battles in Ahmedabad [AFP]](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/2c7d82_01b893dcde9b4120a22579687ec13080mv2.webp)

Regional Disparities and the Influence of Socioeconomic Class

Regional disparities have also had a part to play in shaping the experience of rape culture. In states like Haryana, where patriarchal norms and gender discrimination are deeply entrenched, women from disadvantaged backgrounds face increased risks. The 2017 Rohtak gang rape case, which occurred in a state with pronounced gender biases, reflects the severity of sexual violence in such regions. Conversely, while states like Kerala have higher literacy rates and more progressive gender norms, sexual violence remains a persistent issue, demonstrating that rape culture affects regions differently but remains widespread across the country.

Moreover, recent high-profile cases like the Unnao and Kathua rapes further illustrate the intersectionality of rape culture.

The Unnao case of 2017 involved the gang rape of a young woman by the associates of Kuldeep Singh Sengar, a former Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA).

This case became a focal point for discussions on the intersection of political power and sexual violence. Despite the victim’s repeated pleas for justice, initial police inaction and political interference delayed legal proceedings. This reflected the complicity of institutional power in perpetuating rape culture. Similarly, the Kathua case of 2018 involved the abduction, rape, and murder of Asifa Bano, an eight-year-old Muslim girl in a predominantly Hindu area. This case illustrated how perpetrators can weaponize sexual violence in communal conflicts. The accused celebrated one another, further demonstrating the intersectionality of communal and gender-based violence.

Resistance and Activism

Although the preceding discussion paints a grim picture of India’s battle against such heinous crimes, various forces are indeed working to challenge systemic violence and advocate for justice through grassroots movements, social media activism, and international influence.

For instance, the Gulabi Gang, led by Sampat Pal Devi, focuses on empowering women and tackling issues like domestic violence and sexual harassment in Uttar Pradesh. The group has been instrumental in intervening directly in cases of violence, staging public protests, and pushing for women’s rights. Concurrently, Sayfty, a feminist organization, offers support services to survivors, including legal aid and counseling, while also conducting educational workshops on gender sensitivity. These grassroots efforts demonstrate how localized activism can drive meaningful change and provide crucial support to those affected by sexual violence.

![Picture of the Gulabi Gang [Aljazeera]](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/201422610285372734_20.webp)

The Impact of Social Media and Youth Activism

Moving beyond local initiatives, youth, and social media activism have emerged as powerful tools in the fight against rape culture. As discussed earlier, the #MeTooIndia movement, which drew inspiration from the global #MeToo campaign, has empowered countless individuals to speak out against sexual harassment and violence. This surge in personal testimonies and public discussions on social media platforms has led to increased scrutiny of public figures and institutions.

Alongside this, the Pinjra Tod movement, initiated by students in Delhi, challenges discriminatory rules imposed on female students in universities. This movement advocates for gender equality and the removal of oppressive policies, reflecting a broader push for systemic change.

The Verma Committee and Beyond

![Picture of Justice JS Verma who was part of submitting the report on amendment of criminal law surrounding rape in India [The Hindu]](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Verma_Committee.webp)

Meanwhile, international influence has also played a significant role in shaping India’s response to sexual violence. The global feminist movement has exerted pressure on Indian authorities to improve their handling of such cases. A notable example is the Verma Committee Report, which was commissioned following the 2012 Nirbhaya case. The report proposed several reforms, including the establishment of fast-track courts and stricter penalties for perpetrators. These recommendations were incorporated into the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act of 2013. This marked a significant step forward in addressing sexual violence. Challenges, of course, remain. However, endeavors such as these prove that change is possible. Achieving lasting change requires a sustained commitment to transforming the underlying attitudes, systems, and practices that normalize and perpetuate sexual violence.

Ultimately, dismantling rape culture in India demands a multifaceted strategy. This strategy includes persistent activism, comprehensive legal and institutional reforms, and a cultural shift towards gender equality. Through these concerted efforts, it is possible to build a more equitable and just society. In such a society, sexual violence is neither tolerated nor normalized.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own. They do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of the South Asia Times.

![Ukrainian and Russian flags with soldier silhouettes representing ongoing conflict. [Image via Atlantic Council].](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/2022-02-09T000000Z_1319661209_MT1NURPHO000HXCNME_RTRMADP_3_UKRAINE-CONFLICT-STOCK-PICTURES-scaled-e1661353077377.jpg)