Based on the thread initiated by Dr. Hassaan Bokhari (@shbokhari13), we are presenting the subject matter in its more expansive format. Enjoy reading!

In 1947, Pakistan was truly a unique country whose two parts were separated by 1000 miles of hostile territory and whose eastern part (with the majority of its population) was almost completely surrounded by its hostile neighbor. It was crystal clear that extraordinary efforts and mechanisms would be needed to manage this geographically anomalous country. Aside from geography, there were important differences between East and West Pakistan related to culture, climate, economy, and security requirements. These differences between the two wings were a major cause of deadlock in the constitution-making process of the new state and eventually led to the First Martial Law. The first constitution of Pakistan could only be promulgated in 1956.

PAKISTANI POLITICS

By 1956, a large number of important events had altered the political landscape of Pakistan. In 1951, Prime Minister Liaqat Ali Khan was assassinated. Then Governor General Khwaja Nazimuddin had taken over as PM, and the bureaucrat Ghulam Mohammad had taken over the post of Governor-General. The ruling party, i.e., the Muslim League, did not have a proper grassroots organization before 1947, and its ranks were full of unscrupulous kleptocrats, former touts of the British government, and feudals. This ragtag bunch of politicians was not up to the task of running an independent country, and thus it had to rely heavily on the help of bureaucrats like Ghulam Mohammad. As a result, the bureaucrats of the Civil Service of Pakistan (CSPs) became the dominant political force in the country. The other organized force, i.e., the Army, was at this time operating from the shadows through its chief, General Ayub Khan.

The CSPs were used to the colonial style of governance with a centralized system. In economic management, they favored the British model of centralized capitalism. Similarly, the army followed British conventional models and racist practices like martial-race classification for recruitment. This hybrid CSP-Muslim League model of governance was very unpopular in East Pakistan, whose share of CSPs was less than 5% of the total at this stage. Besides, the Muslim League had also become unpopular following the food crisis and the language agitation. The rising resentment against the incumbent setup was vividly seen in the first provincial elections after independence in East Pakistan in March 1954. To counter the incumbent Muslim League, all opposition parties, including the Nizam-e-Islam Party, the Ganatantri Dal, the Awami League led by Suhrawardy, and the Krashik Saramik Party led by A. K. Fazl-ul-Huq, had formed an alliance called the United Front. The United Front wanted Bengali as a national language and complete autonomy for East Pakistan, leaving only defense, foreign affairs, and currency with the center. But the chief trump card for the United Front was the Muslim League’s unpopularity. Nevertheless, the results even shocked the victors when the United Front won 223 of 237 Muslim seats and the Muslim League won only 10. The incumbent Chief Minister, Nurul Amin, lost to a virtually unknown candidate. The United Front government could only survive for two months, though. Soon after the victory, serious fissures developed between the Chief Minister, Fazl-ul-Huq, and the Awami League. Fazl-ul-Huq didn’t even pick a single Awami Leaguer in his cabinet at first, despite the fact that the Awami League had won more seats than his Krashak Saramik Party. Then the bloody 1954 Karnaphuli Paper Mill and Adamjee Jute Mill riots which left hundreds dead raised huge question marks on his administration. Some argued that these riots were instigated by the center to use as a pretext to dismiss the United Front government, whereas others argued that the hate spewed by the United Front politicians during the election campaign had a pivotal role in precipitating the riots, which took the shape of Bengali versus Bihari refugee encounters. The reality was somewhat more complex than these simplistic narratives, but after these riots, Huq was dismissed and governor rule was imposed in the province. East Bengal wasn’t the first province in Pakistan to experience the undemocratic step of governor rule. Previously Punjab in 1949 and Sindh in 1951 had undergone the same. This practice was basically favored by the CSPs, who were more prone to rule by decree like the Gora Sahibs of the past than to follow democratic norms and procedures.

The politicians themselves were more interested in wealth and power than democratic norms or the country’s welfare, though. Horse-trading was endemic (Fazl-ul-Huq allegedly bought many Awami Leaguers after the election to strengthen his hand), and the politicians were only too glad to accept the patronage of figures like Ghulam Mohammad to further their chances of obtaining wealth and power. As Governor General, Ghulam Mohammad took full advantage of the weakness of politicians and trampled over any vestiges of democracy left in Pakistan. In 1953, he dismissed Khwaja Nazimuddin from the post of PM and appointed the pliant Mohammad Ali Bogra. A year later, he dissolved the first constituent assembly (abusing his emergency powers). He was replaced as Governor General by another bureaucrat, Iskander Mirza, who belonged to the family of Mir Jafar of Bengal (of Plassey fame). In August 1955, Iskander Mirza appointed another bureaucrat (but one who was known for his honesty and integrity), Chaudhry Mohammad Ali, as the PM whose coalition government was supported by the Muslim League, the Awami League, and Iskander Mirza’s own creation: the Republican Party (which was full of habitual turncoats and electables). Ch. Mohammad Ali prioritized the constitution-making process, and finally, the first constitution was promulgated in March 1956 after much compromise between both wings. East Pakistan wanted a unicameral legislature with 55% seats for East Pakistan, Bengali as a national language, joint electorates, and complete provincial autonomy. The demands regarding the Bengali language and joint electorates were accepted, but on the other two points, West Pakistan got its way. The 1956 Constitution postulated a unicameral legislature with a total parity of seats (150 each) between the two wings of the parliament. The constitution granted some powers to the provinces, but overall it espoused a centralized system. The four provinces of West Pakistan were merged into one unit, and the federation was composed of just two wings.

FIRST MARTIAL LAW

The 1956 Constitution was a flawed but pivotal document. It was the product of nine years of effort that had yielded a consensus after numerous compromises by both East and West Pakistan. Finally, it was hoped that Pakistan could now focus on its development after extricating itself from the constitutional quagmire. Sadly, it was not to be. The Governor General, Iskander Mirza, was fond of monarchies and wanted to rule Pakistan like a king. He never let niceties like democratic or constitutional principles hinder him in this quest. Iskander Mirza became Pakistan’s first president under the 1956 constitution. He stayed in this post for two and a half years. During these 30 months, he dismissed 4 prime ministers, 6 chief ministers of East Pakistan, and 3 chief ministers of West Pakistan. At the federal level and in West Pakistan, he used his Republican party to engineer or demolish governments. In East Pakistan, he used the rivalry between Fazl-ul-Huq (who served as Governor of East Pakistan under Mirza for 2 years) and the Awami League under Suhrawardy to dismiss chief ministers at will. Between 1956 and 1958, East Pakistani politics became a cynical dark comedy with shifting loyalties, open trading of posts for money, and startling corruption. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman also became a provincial minister during this era and greatly “improved” his financial status as a result. The East Pakistan governments of this era proved even more inept than the previous Muslim League government (1947–54), and as a result, the inter-wing disparity grew. Funds allocated by the federal government to East Pakistan either filled the ministers’ coffers or were left unused. This state of affairs suited Iskander Mirza, who didn’t want competent leadership to attain popularity and hence develop the strength to challenge his rule.

At the federal stage, Chaudhry Mohammad Ali was removed in September 1956, and Hussain Suhrawardy finally became the PM of Pakistan. Suhrawardy commanded huge popularity in East Pakistan and was also reasonably popular in West Pakistan. This made him a genuine all-Pakistan leader. He managed the economy well and tried to lead Pakistan towards a balanced foreign policy. Suhrawardy wanted Pakistan to establish close relations with both the USA and China, whereas the civil-military official duo of Iskander Mirza and General Ayub Khan wanted a fully pro-US foreign policy. In Suhrawardy’s tenure, East Pakistan enjoyed a real and equitable share of power at the national level, and this did ease the inter-wing polarization. Suhrawardy’s popularity ultimately made Iskander Mirza insecure, and he was forced to resign after the Republican Party took back its support in October 1957.

On September 23, 1958, an awful incident took place in the East Pakistan provincial assembly when a fight broke out between opposing groups of legislators. Deputy Speaker Shahid Ali was injured during the fight and died two days later. This incident signified the level of chaos that had become the hallmark of East Pakistani politics. A few days later, this incident was used by Iskander Mirza as one of the justifications for his proclamation of the First Martial Law in Pakistan.

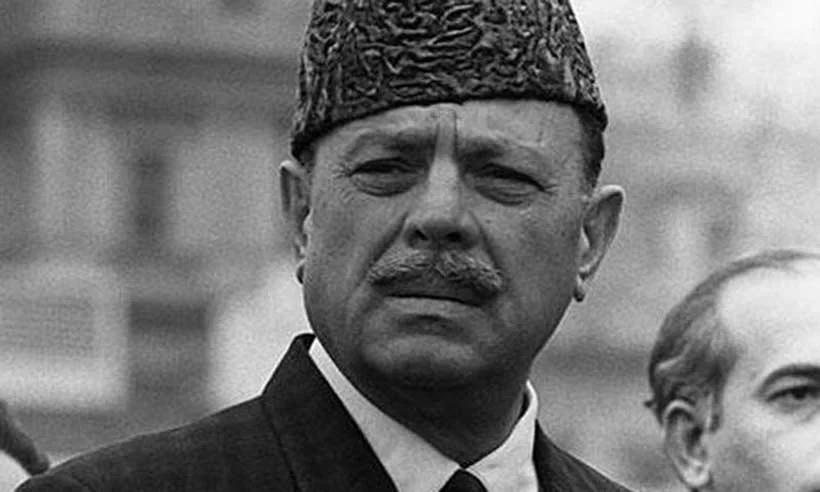

On October 7, 1958, President Iskander Mirza declared the First Martial Law in the country and abrogated the constitution with the help of his partner-in-crime, General Ayub Khan. The reasons given for this step were economic turmoil borne out of political instability, which in turn was the product of the “unworkable” and “dangerous” constitution hence leading to the First Martial Law. Thus, the consensus that took nine years to achieve was destroyed by an undemocratic and dictatorial act merely two and a half years later.

Here we might ask ourselves the question of whether the political stability was caused by a “flawed” constitution or by unscrupulous politicians, of whom Iskander Mirza was himself the foremost. Where was it written in the constitution that the President should make a king’s party through bribery and inducements and then use that party to demolish several central and provincial governments in order to further his own power? Why weren’t the elections scheduled for 1957–58 repeatedly delayed in contravention of the constitution? In reality, it was Iskander Mirza’s fervent desire to cling to power that brought on the martial law because he feared that his unpopularity would result in the end of his political career after the scheduled elections in early 1959. So, he abrogated the constitution. Nip the election in the bud!

Alas! Iskander Mirza ignored a critical point. With no constitution, there was no legal basis for the office of president either. He could only continue as president as long as General Ayub, the martial-law administrator, wished. That period turned out to span three weeks, and Mirza was packed up like used luggage and sent to London to live his life in exile.

General Ayub Khan had an epiphany one fine night in the Dorchester Hotel, London, that the politicians were the cause of all of Pakistan’s ills and only an honest military dictator could rescue the country. He even made the outline of a draft ideal constitution that fateful night. He bided his time for 4 years and cemented his own and the army’s position as a bedrock of stability amidst all the chaos on the political scene. Iskander Mirza provided him with the opportunity to put his vision into action. Ayub banned all the corrupt politicians from politics with ordinances like the EBDO and banned all political activity under martial law as well. He was received with much enthusiasm in West Pakistan. Even in East Pakistan, he was initially welcomed. He assembled a hand-picked cabinet composed of talented young men like Z. A. Bhutto and Manzur Qadir and his trusted military generals. The first “democratic” experiment in Pakistan had ended. It had delegitimized the politicians and utterly failed in providing good governance, justice, and opportunities to the people of Pakistan. It had miserably failed to establish Pakistan on the basis of the foundational ideology espoused by the likes of Iqbal.

At that point in time, the first experiment with military rule had begun.

Would the generals have succeeded where the politicians had failed so ignominiously

Your go-to editorial hub for policy perspectives and informed analysis on pressing regional and global issues.

Add a Comment