Hindutva, as a socio-political ideology, promotes an exclusionary narrative that frames Indian civilisation as solely and purely Hindu in nature and character. Much like gerrymandering, which manipulates electoral boundaries for political gains, Hindutva seeks to distort, fabricate, and cherry-pick Indian history, sacrificing historical accuracy and pluralism to advocate Hindu nationalism and cultural supremacy. This very notion amounting to the civilisational Gerrymandering of Indian History’ serves as a foundation to argue how Hindutva fails the scrutiny of the Subcontinent’s rich history and academic evaluation of what constitutes Indian civilisation.

Also See: Hindutva: India’s Dangerous Export to the World

What is Hindutva? Its Definition and Genesis as a Socio-Political Ideology

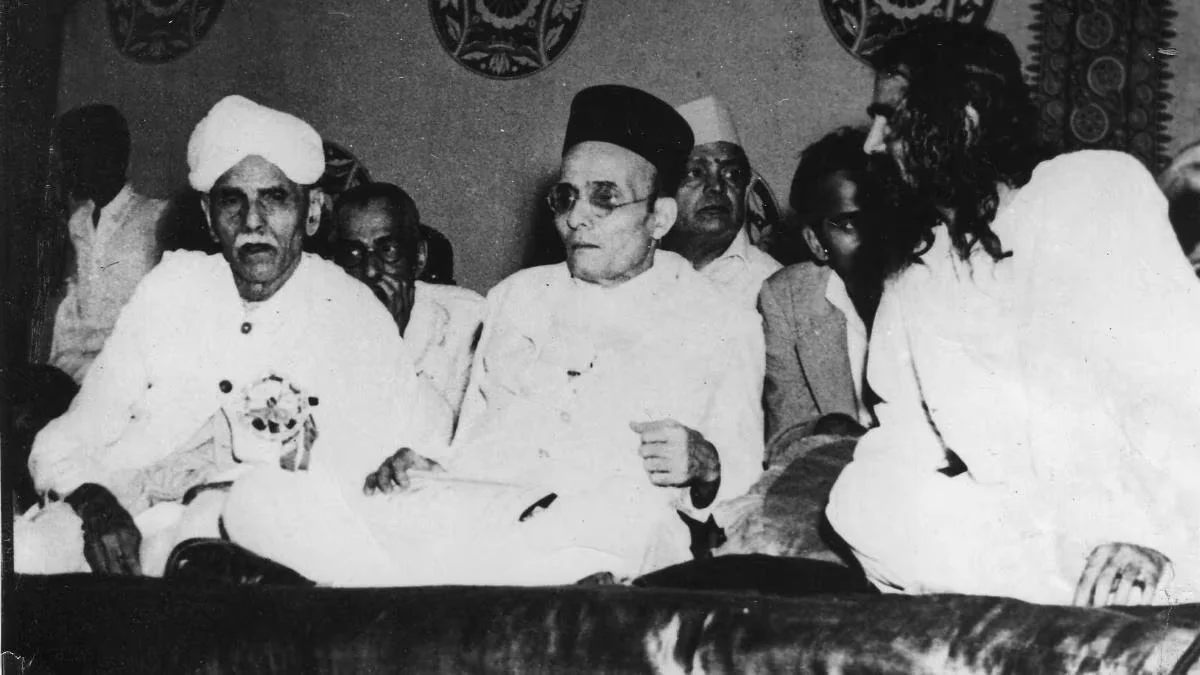

Hindutva, unlike Hinduism as a vibrant and inclusive religion, is a socio-political movement rooted in cultural nationalism and the Hindu-dominant identity of the Subcontinent. Emerging in the early 20th century, it was primarily shaped by the works of V.D. Savarkar and M.S. Golwalkar.

Savarkar’s seminal book, Hindutva: Who is Hindu? (1923), laid the ideological groundwork for the movement. Golwalkar expanded on this framework in his book We or Our Nationhood Defined (1939), further embedding Hindutva’s theoretical structure.

- Savarkar defined Hindutva not as a religion but as the “essence of being Hindu,” describing India as a Pitribhoomi (Fatherland) and Punyabhoomi (Sacred Land) for Hindus, united by common ancestry, geography, and culture. His writings present a narrow view of India’s diversity, as reflected in this quote:

“India, that is Bharat, has always been a land of Hindus. Its unity transcends political borders and is rooted in the sacred geography and culture of Hindutva.” - Golwalkar went further to argue that only Hindus constitute the “national race” of India, deeming Muslims and Christians as “foreign elements” due to their religious roots outside India. In We or Our Nationhood Defined, he wrote:

“The foreign races in Hindustan must either adopt the Hindu culture and language… or may stay in the country wholly subordinated to the Hindu nation.”

This ideology disregards the historical pluralism and syncretism of Indian society. Golwalkar also rejected the Congress Party’s vision of a united, inclusive Indian nation, discrediting it as an idea that does not “hold water.”

The Institutionalisation of Hindutva

Following the publication of Savarkar’s work, K.B. Hedgewar institutionalised Hindutva by founding the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) in 1925.

Today, Hindutva operates under the auspices of the Sangh Parivar 1, an umbrella organisation spearheaded by RSS and including entities like Bajrang Dal, Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

The BJP, an ideological offspring of the RSS, officially adopted Hindutva in its 1996 political manifesto. The rise of Narendra Modi in 2014 has marked a turning point, with Hindutva making irreversible inroads into Indian polity.

Hindutva: Roots in Colonialism and Misappropriation of Sociocultural Movements

The historical roots of Hindutva lie in colonial-era narratives and the rise of ultra-nationalism in 20th-century Europe.

Colonial writers2, in their narrow interpretation of Indian history, posited that India was a “Hindu society” before the Muslim invasions, which they claimed brought forced conversions. This narrative fostered a victimhood mentality among Hindus and ignored the cultural fluidity that characterised pre-colonial Indian society3. Prashant Waikar notes:

“Colonial history deepened communal schisms by failing to acknowledge the inherent syncretism of Indian culture.”

Hindutva ideology also draws inspiration from European ultra-nationalism, particularly German Nazism. Golwalkar controversially praised Hitler’s racial purity policies:

“To keep the purity of the race and its culture, Germany shocked the world by her purging of Semitic races—the Jews… a good lesson for us in Hindustan to learn and profit by.”

Additionally, Hindutva misappropriates the socio-cultural reform movements of 19th-century India, such as the Bengali Renaissance and Brahmo Samaj.

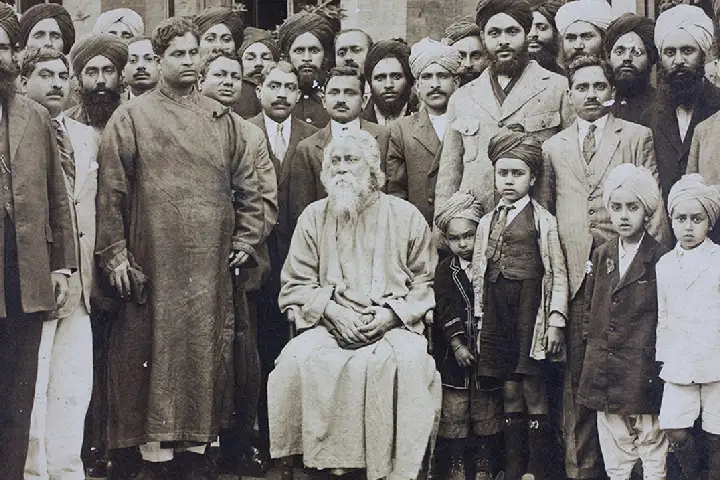

- The Bengali Renaissance, led by thinkers like Raja Ram Mohan Roy and Rabindranath Tagore, aimed at reform and modernity while celebrating inclusivity and progressiveness. Hindutva ideologues, however, distort these movements to fit their agenda of cultural dominance, ignoring their pluralistic ideals.

Partha Chatterjee4 aptly summarises this misappropriation:

“While the Bengali Renaissance was about reform and modernity, Hindutva distorts its focus into a conservative, narrow version of Hinduism.”

Similarly, the Brahmo Samaj is often co-opted by Hindutva to align with its monolithic and nationalist vision, disregarding its inclusive principles. Christophe Jaffrelot5 highlights:

“The Brahmo Samaj, though progressive in its reform, is misappropriated by Hindu thinkers to bolster a Hindu-only narrative.”

Mechanism of Gerrymandering Project: Hindutva Ideologues and Civilisational Gerrymanderingof India

Hindutva ideologues, the Civilisational Gerrymanderers of Indian history, execute their agenda by first espousing a flawed conception of civilisations as insular and compact blocks. They view syncretism between different cultures, ethos, and ideologies as a historical aberration requiring redressal and purification.

Redefining Civilisation

For instance, Gowalker’s insistence on only Hindus constituting the “national race” with a common ancestry and pure Sanskriti (culture) reveals how gerrymandering begins with redefining civilisation itself.

Sanskritisation and Erasure of Composite Culture

Secondly, Hindutva ideologues aim to Sanskritise Indian culture by erasing symbols reflective of its composite nature. Renaming cities like Allahabad to Prayagraj and Mughal Gardens to Amrit Udyan exemplifies their goal to purge Indian soil6 of symbols deemed representative of “foreign rule”.

Manipulation of Curricula

The third mechanism involves altering educational curricula, downplaying contributions by non-Hindus at the expense of academic integrity and historical authenticity.

Exclusionary Legislation

Exclusionary legislation, such as the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) of 20197, offers citizenship to all migrants except Muslims. This aligns with Hindutva’s goal of defining citizenship based on Hindu identity. Similarly, the revocation of Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir in 20198 and the inauguration of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya further illustrate Hindutva-driven mechanisms.

Misappropriation of Historical Narratives

Lastly, the Hindutva project involves misappropriating India’s past empires as exclusively Hindu. For example, the Gupta dynasty (320-550 CE) is touted as the “Golden Period of Hinduism,” disregarding its pluralistic ethos.

Critiquing the Gerrymandering Project

India’s historical development is marked by civilisational syncretism, beginning with the Indus Valley Civilisation (3300-1300 BCE). Historians like Kenoyer (1998)9 argue that sacred symbols such as Proto-Shiva and Swastika reflect spiritual practices later incorporated into Hinduism. Romila Thapar10 (2002) highlights the synthesis of Aryan and non-Aryan traditions during the Rigvedic period (1500-500 BCE), resulting in a multifaceted Hinduism.

Reformist Movements: Buddhism and Jainism

The rise of Buddhism and Jainism in the 6th century BCE as reformist movements against Vedic orthodoxy ushered in an era emphasizing Ahimsa (non-violence) and spiritual equality. These movements left lasting imprints on Indian art, society, and statecraft. For instance, Jain traditions shaped early Mauryan policies of non-violence.

Mauryan Empire: A Pluralistic Foundation

The Maurya Empire (321-185 BCE), established by Chandragupta Maurya, exemplified political pluralism and pragmatism. Emperor Ashoka’s conversion to Buddhism after the Kalinga war led to secular governance and economic integration, as noted by Romila Thapar11:

“The Bhudist Sangha acted as nodes of commerce, linking traders and merchants across regions, thereby fostering economic integration”. In the same vein, writers Kulke and Ruthermond, (2004) note that “Ashoka’s Dhamma was a secular policy that promoted ethical governance beyond the bounds of religion”.

Similarly, “the Ghandara School of Art, blending Greco-Roman and Indian influences” notes Behl (1998) “emerged under Bhudist patronage, illustrating the syncretic nature of Indian culture”.

Contributions of Other Religions

Writing about the contributions of Sikhism in Indian civilisation Grewal notes: “ The Sikh resistance redefined the politics of equality and justice in early modern India”.

Christianity

Christianity entered India in the first century through St. Thomas, the apostle and later through European missionaries.

Susan Bayley (1989)12. believes that the social reforms in India were “pionered by early Christian Missons” and they also played an instrumental role in opposing caste discriminations in India.

Frykenberg (2008) writes “Christian missions were among the first to question the entrenched caste hierarchies in colonial India”. Moreover, Christianity has also played a key role in India’s education, literature and architecture.

Sikhism

Sikh resistance redefined equality and justice in early modern India. Writing about the contributions of Sikhism in Indian civilisation Grewal notes: “The Sikh resistance redefined the politics of equality and justice in early modern India” 13.

Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrians played a cardinal role in philanthropy and Industrialization. Parsi Industrialists like J.N. Tata laid the foundation for India’s modern industries14.

Islam

Islam’s advent in India began in the 7th century through trade and later through conquests. Islam has ever since left indelible imprints on Indian ethos, statecraft, culture, and literature. The Mughul empire and Delhi sultanate introduced centralised governance, judicial system, and revenue reforms.

“Akbar’s policy of Sulh-i-kul (global tolerance)” writes Richard’s (1993) “exemplified a sophisticated governance model based on Pluralism”.

The Bakhti and Sufi movements paved the way for interfaith dialogue. These dialogues between Bakhts and Sufis “enriched India’s sipirtual tradition” observed Amartya Sen, (2005 “creating shared spaces for coexistence”.

The development of coastal hubs like Surat and Calicut happened through Muslim merchants as Irfan Habib (1999) notes: “The Islamic period saw a flourishing of inland and maritime trade, connecting South Asia to global markets. Art and architecture under Mughul patronage achieved great sophistication and grandeur. Qutub Minar, Taj Mahal and Red fort stand out as paragons of architectural grandeur and are reflective of Indias syncretism civilisation”. Moreover, Amartya Sen testified: “The interaction of Islamic rulers and Indian traditions produced rich syncretic cultures” (2005).

British Colonial Legacy

The British rule from 1757 to 1947 introduced modern institutions such as bureaucracy, parliamentary democracy, and judiciary. While exploitative, these projects along with the modern education system, they served to modernise Indian society. Bipan Chandra (1989) writes: “The British laid the foundations of a centralised state, albeit for colonial exploitation”15.

In short, the Indian civilisation didn’t evolve in an insulated civilisational block free from all non-Hindu influences.

![An Indian Grandee of the East India Company depicted riding in the Indian procession, 1825-1839. [Photograph: Getty Images].](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/5055.webp)

Civilisation: Definitions and Hindutva’s Flawed Ideology

Now if we turn to some of the highly regarded anthropologist and historians and their definitions of civilisations we will see that how their idea of civilisation is not even remotely in sync with the ideology of Hindutva.

Moreover, the definitions they offer counter Hindutva’s narrow interpretation of civilisation:

- Edward Burnett Taylor for instance, looks at civilisation as “the complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society”16.

- For Will Durant, civilisation is “social order promoting cultural creation”.

- Emile Durkheim views it as a “set of shared moral and cultural frameworks”17.

- Max Weber sees civilisation through the prism of “material and immaterial achievements embedded within institutions, laws and values.” 18.

India’s kaleidoscopic landscape, rich with myriad languages, religions, arts, sciences, and philosophies, owes its civilisational syncretism to the profound contributions of diverse religious identities, including Buddhists, Jains, Zoroastrians, Muslims, and Christians—an enduring legacy that stands in stark contrast to the exclusionary views of Hindutva.

Hinduism and Iconic Figures

Hindutva ideology is divorced from the understanding of Hinduism by figures of the late nineteenth and twentieth century, like Swami Vivekananda, Rabindranath Tagore, and Mahatma Gandhi.

Swami Vivekananda’s 1893 Chicago speech celebrated Hinduism’s universal tolerance. He declared, “I am proud to belong to a religion which has taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance. We believe not only in universal toleration, but we accept all religions as true.”

In contrast, Gandhi’s principles of non-violence oppose Hindutva’s exclusionary stance, reflecting a broader, inclusive interpretation of Hinduism.

Hindutva’s Challenge to Civilisational Gerrymandering of India

India, as a rich and diverse civilisation, has always been a melting pot of cultural confluence, philosophical and traditional synthesis, and ideological assimilation. This fusion, unfolding over millennia, has shaped its unique civilisational syncretism. It has never been culturally insular, religiously compact, ideologically impermeable, or a racially Hindu civilisation, as the “Gerrymanders of Indian civilisation”—the ideologues of Hindutva—would have us believe.

The early Maurya and Gupta empires laid the foundation for its cultural and political structures. The Delhi Sultanate and local kingdoms facilitated the blending of diverse traditions and cultures. The Mughal period marked the zenith of cultural synthesis, architectural grandeur, and political pluralism. The British colonial era, while marked by economic exploitation, also introduced modern institutions and infrastructure.

This civilisational syncretism is evident today in India’s cuisine, languages, literature, architecture, festivals, and political and economic institutions. Contributions from people and kingdoms of various religious identities have created a civilisation so remarkable that even Winston Churchill described it as a “miracle.”

Ideologies like Hindutva not only made the partition of India historically inevitable but also pose a grave threat to the regional stability of South Asia today. By promoting the reprehensible concept of Akhand Bharat, which seeks to subsume much of South Asia under a single Hindu-only state, Hindutva undermines the pluralistic ethos of the region. The first step in countering such threats is to instil historical clarity in the minds and hearts of South Asian people—a clarity that can only be achieved through rigorous historical scrutiny and incisive academic evaluation of Hindutva ideology.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own. They do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of the South Asia Times.

- https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/On-the-Bajrang-Dals-borth-evolution-and-activity/article62116497.ece ↩︎

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.13169/islastudj.4.2.0161 ↩︎

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/42981698 ↩︎

- https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/128956?ln=en ↩︎

- https://archive.org/details/hindunationalist00chri ↩︎

- https://asiatimes.com/2021/05/hindutva-an-assault-on-indias-future/ ↩︎

- https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/03/india-citizenship-amendment-act-is-a-blow-to-indian-constitutional-values-and-international-standards/ ↩︎

- https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/kashmir-the-effects-of-revoking-article-370/ ↩︎

- Kenoyer, J. M. (1998). Ancient cities of the Indus valley civilization. Oxford University Press; American Institute of Pakistan Studies. ↩︎

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/24453059 ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Bayly, S. (1989). Saints, goddesses and kings: Muslims and Christians in South Indian society 1700-1900. Cambridge University Press. ↩︎

- Grewal, J. S. (1998). The Sikhs of the Punjab (Vol. 2). Cambridge University Press. ↩︎

- Luhrmann, T. M. (1996). The Good Parsi: The Fate of a Colonial Elite in a Postcolonial Society. Harvard UP. ↩︎

- Chandra, B. (1989). Study of the Indian national movement some problems and issues. Minamiajiakenkyu, 1989(1), 22-40. ↩︎

- Tylor, E. B. (2021). The science of culture [1873]. Readings for a history of anthropological theory, 19-31. ↩︎

- Durant, W. (2002). Heroes of history: A brief history of civilization from ancient times to the dawn of the modern age. Simon and Schuster. ↩︎

- Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology (Vol. 1). University of California press. ↩︎

![India’s history has always been diverse, yet Hindutva seeks to rewrite it through civilisational gerrymandering of India. [Image via Shutterstock]](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/SAT-Web-Banners-13.webp)

![Ukrainian and Russian flags with soldier silhouettes representing ongoing conflict. [Image via Atlantic Council].](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/2022-02-09T000000Z_1319661209_MT1NURPHO000HXCNME_RTRMADP_3_UKRAINE-CONFLICT-STOCK-PICTURES-scaled-e1661353077377.jpg)