The Re-Emergence of Terror: Afghanistan as a Global Terrorist Hub

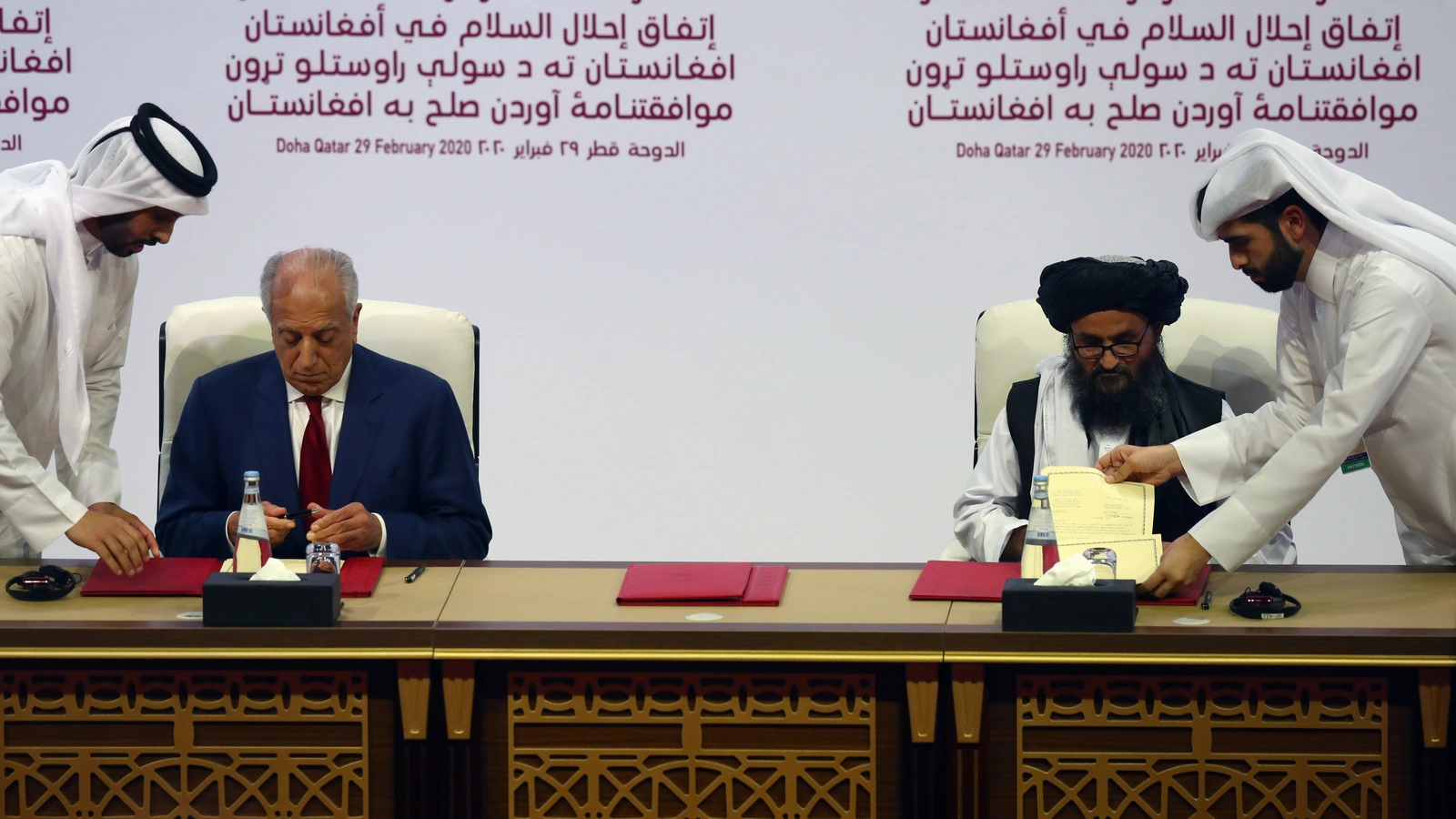

The Taliban’s return to power has revived Afghanistan’s role as a global Terrorist hub. Despite pledges under the 2020 Doha Agreement, the regime continues to shelter and enable groups such as Al-Qaeda, TTP, and ETIM, creating a volatile nexus of terrorism that threatens regional stability and global security. As internal conflicts deepen and governance collapses, Afghanistan’s transformation into an ideological sanctuary ensures a cycle of chaos and suffering that primarily victimizes its own people.