Political Theology has recently generated a lot of discussions and debates in the Euro-America academy, exposing the theological underpinnings of modern state. Most often traced to the German theorist Carl Schmitt. In his influential work, “Political Theologies” Schmitt argues that:

“All significant concepts of the modern theory of the state are secularised theological concepts not only because of their historical development—in which they were transferred from theology to the theory of the state, whereby, for example, the omnipotent God became the omnipotent lawgiver—but also because of their systemic structure.”[1]

Theological Underpinnings of Modern Institutions

One way to engage with this category of Political Theology can be approached is to think about ways in which the modern institution, like the modern state, is indebted to the language of theology, even though the prevailing notion of liberal democracies claims that it has overcome religious theology. In other words, modern political logic is deeply indebted to the theological logics of operations. As argued by Graham and Lupton :

“The exchanges, pacts, and contests that obtain between religious and political life, especially the use of sacred narratives, motifs, and liturgical forms to establish, legitimate, and reflect upon the sovereignty of monarchs, corporations, and parliaments.”[2]

Political theology is not the same as religion.” Rather, political theology presents an important conceptual key to unlock the operations of secular power in such varied yet interconnected discursive avenues as religion, law, literature, politics, science, and economics.[3]

What is Sovereignty?

Sovereign is the one who can decide on the state of exception, the exception to the normal rule or normativity. The concept of sovereignty is one such form-property that remains, despite the changes of states and political orders in the last two centuries, one of its hallmarks. While all pre-modern rule was sustained by certain political and ideological structures, the modern state is unique in its impersonal character, an abstract concept that lies at the heart of its legitimacy.[4] The state is not the secular arrangement that purports it to be. Rather the sovereignty of the secular modern state is similar to divine sovereignty, hinging to the capacity to enact exceptions to the rule.[5]

Arguably this has generated a lot of attention to critically engage Schmitt to question the self-congratulating narrative of a secular modern break from previously theological political order. Before that, the modern state was considered natural and a continuation of the previous forms of governance and states that are disconnected from theology. Politically and ideologically, sovereignty is constructed around the concept of will to representation. To speak of the modern state is by necessity to include the form-property of sovereignty and in turn to include the “popular-will” as the master of one’s own collective destiny.

Sovereignty has two dimensions in modern sense.

- International

- Domestic

Internationally, sovereignty means that each state recognizes other state authority within their respective borders and it legitimately represents the “popular will” of the respective nation. The international arrangement, mapped out in principle in the aftermath of the so-called Peace of Westphalia (1648), is structurally connected with the domestic dimension. Within a nation’s borders there is no order higher than that of the state. Its law is the law of the land. It cannot be revoked and cannot as a law be appealed to any higher order. The fiction has proven so successful and powerful that even when everyone knows that a regime is unrepresentative and even oppressive, it is still deemed to speak legitimately on behalf of its citizen/nation. To come into existence, sovereignty needs not only a state but also the general prerequisite of an imagined construct.[6]

Carl Schmitt argued that, as a sovereign being, the state’s “decision has the quality of being something like a religious miracle: it has no reference except the fact that it is.”[7] The metaphysical image that a definite epoch forges of the world has the same structure as what the world immediately understands to be appropriate as a form of its political organization.[8]

Transition in Europe: From Transcendence to Immanence

![Canaletto’s "The Procession on the Feast Day of Saint Roch" illustrates 18th-century political theology, showing the union of church and state in Venice [Image via National Gallery, London].](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/BN-TL795_EYEWIT_750RV_20170516110958.webp)

The transition from transcendence to immanence is a key development in the history of European political theology from the early modern period. The pushing aside of the sovereign as the sole law-giver of his kingdom was replaced by radical democratic sovereignty replacing the previous monarchical one. Royalism came to an end because sovereignty no longer existed in the traditional sense and the 17th and 18th centuries were dominated by the idea of sole sovereign in the domain of politics and theology.[9]

In the early modern period, it was the time in Europe when a fundamental change in the view of nature occurred. Suddenly, nature acquires a new vision and a new meaning. Nature was no longer a kingdom of God but something instrumental at the disposal of humans. By the time Europeans started reformation movements they realised that they had to rethink their conception of nature, God, cosmology, and metaphysics.[10]

Modernity was a reaction to the political and religious abuses of the clergy in Europe.

These developments were directly tied to the changing and evolving conception of God, cosmology, and metaphysics in Europe which engendered a new conception of political and political theories. The decisive quality that distinguished this new consciousness of democracy from its older monarchical counterpart was its complete intolerance for the state of exception, which in theological terms signifies miracles and dogmas that transcend human comprehension and critical doubt.[11] Democracy is the expression of a political relativism that is liberated from miracles and dogma.[12]

Islamic World and Sovereignty in the Subcontinent

![Mughal King Akbar in the Darbar [Image via Almay].](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/1_gg_b375Gu3dkxjZrP23O5w.webp)

In the pre-modern Islamic world particularly in the Subcontinent, Mughal understandings of political sovereignty were premised on the conjunction of kingship and sainthood. The sovereignty of the king was organized and performed according to the logic and grammar of the Sufi saint’s charisma, suffused with millenarian authority and expectation. Kingship was interlocked with sainthood in a “mimetic embrace”.[13] These interconnected milieus offer an ideal window to explore and rethink the relationship between Muslim kingship and sainthood. For it was here that Muslim rulers came to express their sovereignty and embody their sacrality in the manner of Sufi saints and holy saviours.

The Mughal dynasty of the subcontinent (1526–1857) and the Safavid one of Iran (1501–1722) exemplified this mode of sacred kingship. Discipleship became a Mughal imperial institution under Akbar and evolved after him, and Shah Ismail became the hereditary leader of the Safavid Sufi order in northwestern Iran.[14] Akbar’s millennial project in India evoked comparisons with Shah Ismail’s militant messianism in Iran is indicative of a strong similarity between the two enduring Muslim empires of sixteenth-century Iran and India. It brings into focus the startling fact that both Islamic polities, in their formative phases, had seriously engaged with messianic and saintly forms of sovereignty.[15] As argued by Moiz:

“It was no accident that in both these polities a similar style of monarchy developed, in which claims of political power became inseparable from claims of saintly status… Unsurprisingly, then, the greatest of Muslim sovereigns of the time began to enjoy the miraculous reputations of the greatest of saints.”[16]

The “messianic” and “saintly” nature of their sovereignty was adduced by astrological calculations and mystical lore, embodied in court rituals and dress, visualised in painting, enshrined in architecture, and institutionalised in cults of devotion and bodily submission to the monarch as both saint and king.[17]

Transition from Mughal to British Empire: Concept of Sovereignty in Colonial Era Subcontinent

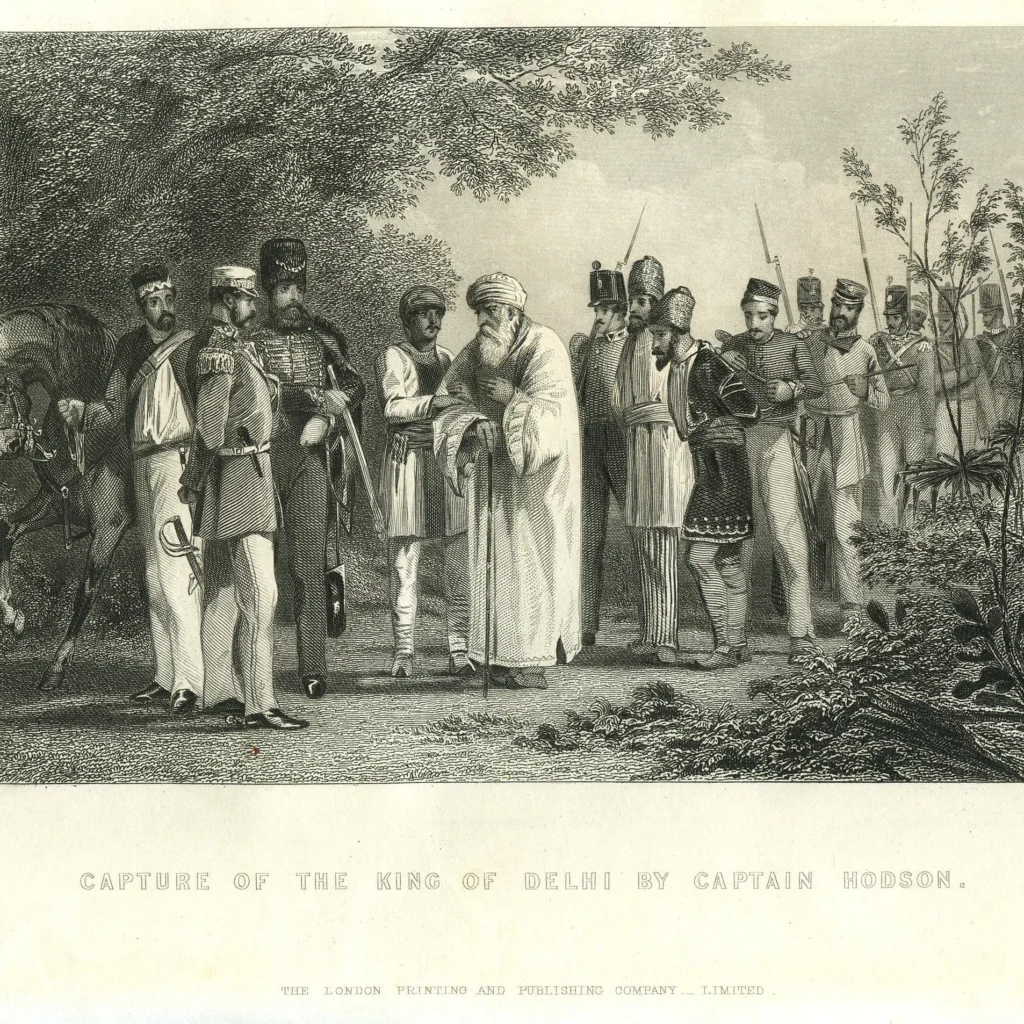

The Sufi sainthood and Kingship conjuncture sovereignty were ruptured only due to the onslaught of colonial modernity. The transition from the Mughal empire to the colonial state is categorised by Sudipta Kaviraja as one from subsidiarity to sovereignty. All states, according to Kaviraja, were subsidiaries before the coming of colonial modernity.[18] Subsidiary states are described as: they dominated society as a group of rulers distinct from the ordinary subjects. Their ability to affect the structure of society and everyday life rituals was seriously restricted. Such a subsidiary state was overturned in the aftermath of 1857 by the sovereign colonial state.

The idea of the sovereign state, with the capacity to actively regulate and make claims on the lives of its subjects, was thoroughly modern.[19] This inherent tension in the logic of British colonial rule remained unresolved until the peasant uprising of 1857, which saw a brutal suppression of the rebellion and the eventual trial and imprisonment (in exile) of the last Mughal king, Bahādur Shāh Ẓafar (d. 1862). After this watershed event, through the Government of India Act of 1858, the British firmly vested in their monarch the political sovereignty of India.

With the collapse of the Muslim political sovereignty, there was an increase in divine sovereignty. This was the political climate that led to the competing political theologies and rationalities. The homogenization of legal text and the essentialization of religion led to inter/intra-religious tensions. Whilst this, a growing middle-class of scholars also emerged and assumed morals and religious authority.

One important development that happened in this transition was, in Professor Tareen’s narrative, the reverse of Carl Schmitt. In which “political debates” entered the “theological” realm. The realisation of the impossibility of resurrecting Muslim political sovereign in the public sphere was seen as the sight of resurrecting that sovereign power. This is why there was a subsequent rise in the debates on public identity markers, and reform movements who wanted to reform the prevailing rituals, customs, and everyday life. In these seemingly theological debates where reform projects were articulated, political expression and anxieties were expressed. As Professor Tareen argued:

“The linchpin of political sovereignty lays its effects on the textual and rhythms of everyday devotional life. The realisation of the impossibility of Muslim political sovereignty in the post-1857 landscape only further intensified the focus on the realm of ritual life and the everyday as the site holding the promise of sovereign power.”[20]

The religious community was the only spoke-person, as custodians of the Muslim sovereignty, for colonial Muslims of the subcontinent. The rationalisation of the focus on the public sphere and ritual realm was to protect the social identity of the Muslims from encroaching on the colonial onslaught.

Competing Political Theologies in the Subcontinent

In the debate between the two early modern scholars of subcontinent Shah Ismail Dhelvi and Fadl-e Haq Khairabadi, there was an implicit discourse of political theology and aspiration in their discussions. When Fadl-e-Haq Khairabadi defended shafa’at intercession (a hierarchical salvation), even the theological language in which he was articulating, was presuming the desirability of hierarchical political order which was the prevailing norm.[21] Fadl-e Haq Khairabadi’s hierarchical salvation corresponds with the competing theologies of that time, i-e

God → Prophet→ Sufi saint→ Ordinary People

King → Princes → Ministers → Advisors → Common People

On the other hand, Shah Ismail when criticised the hierarchical order because he had the conception of a divine-human relationship that is non-hierarchical but horizontal which is still thinkable in the modern moment as strict democratic and it was a new political rationality at that time.

The question of how Muslims should practise their faith and the cultivation of ethical subjects is in fact deeply political. To side-step and stereotype the Muslim intellect debate that it is disconnected from politics and politics is all about the modern state, law and nothing to do with religion cannot hold to scrutiny. Muslim intellectual debates did not explicitly articulate political theories as such but they carry a very sophisticated and complex understanding of politics. As Professor Ovamir Anjum argued, “the political domain of thinking in any thought-world is grounded in its fundamental commitments and often silent presuppositions. Modern scholars have often understood Islamic political thought through the study of classical treatises on the caliphate, but have largely ignored the theoretical underpinnings of political life in epistemology, theology, and legal theory”[22]

Lastly, political theology is not a cause and effect in which the condition of the society changes so the nature of theological debates but it is the intimate entanglement of theology and politics where you cannot separate the cause from effect. Therefore, politics and theology are inseparable. Liberal democracies and political logic are as much indebted to the logic of theology[23] as one that is deemed to be religious, in this Islamic political thought. How we understand God influences our relationship/behaviour with the social world. Paul Kahn has aptly argued that the sovereign state is “conceived as the efficient agency of its own construction . . . comparable to the divine Creation ex nihilo” and “capable of having or expressing such an act of will.”[24] In its full implications, sovereignty has in common with monotheism a host of attributes.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own. They do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of the South Asia Times.

References

[1] Carl Schmitt, Political Theology.

[2] Sherali Tareen, Defending Muhammad ﷺ in Modernity, page 42.

[3] Ibid 42.

[4] Wael Hallaq, Impossible State, page 25.

[5] Sherali Tareen, Defending Muhammad ﷺ in Modernity, page 42.

[6] Wael Hallaq, Impossible State, page 25.

[7] Carl Schmitt, Concept of Political.

[8] Sherali Tareen, Defending Muhammad ﷺ in Modernity, page 43.

[9] Ibid 43.

[10] Peter Frankopan, The Silk Roads; Jonathan Israel, Radical Enlightenment.

[11] Sherali Tareen, Defending Muhammad ﷺ in Modernity, page 43.

[12] Carl Schmitt, Political Theology, page 43.

[13] Sherali Tareen, Defending Muhammad ﷺ in Modernity, page 50.

[14] Moiz Azhar, The Millennial Sovereign, page 3

[15] Ibid 3.

[16] Ibid 3.

[17] Moiz Azhar, The Millennial Sovereign, page 3-4.

[18] Sherali Tareen, Defending Muhammad ﷺ in Modernity, page 45.

[19] Ibid 46.

[20] Prof Sherali Tareen, Perilous Intimacies, page 24.

[21] As previously mentioned, Mughal and Safavid sovereignty were closely tied to Sufi sainthood.

[22] Ovamir Anjum, Politics, Law, and Community in Islamic Thought: The Taymiyyan Moment, page 9.

[23] Even in liberal democracies and political thought, there is a certain relation and status of God in relation to humans which cannot be undermined.

[24] Wael Hallaq, The Impossible State, page 27.