As early as the 1990s, western powers have been involved in offensive cyberespionage. Analysing the interstate engagements of cyber operation, the article determines the anticipated global future of cyber-security and warfare.

Historically, the content and disposition of armies can largely determine the progress of a civilization. From standing armies to capturing territories, armies and warfare have evolved with the passage of time by incorporating new technologies and developments. One such area which has emerged as a new domain of warfare is cyber operations. In the past two decades, cyber operations have emerged as a key statecraft tool for several countries. This analytical piece explains how cyber operations have been integrated with conflicts and how cyber operations are likely to transform the overall landscape of warfare in the future. This analysis only covers the state to state engagements within the cyber domain.

Defining Cyber Operation

This piece relies on the definition of cyber operation presented by the Council of Foreign Relations’ Cyber Operations Tracker. It defines cyber operations as ‘all instances of publicly known state-sponsored cyber activity which include the following seven types:

- Data Destruction

- Defacement

- Distributed Denial of Service

- Doxing

- Espionage

- Financial Theft

- Sabotage

Since 2005, 34 countries are suspected of launching at least 510 publically known cyber operations. Several factors have motivated these states to launch such attacks. The primary motivating factor for states to launch cyber operations is acquiring espionage, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 – Breakdown of Types of State-Sponsored Cyber Operations since 2005 (Source – Council on Foreign Relations’ Cyber Operations Tracker)

Belfer National Cyber Power Index has determined that there are seven national objectives that a state attempts to pursue through cyber operations. These objectives are as follows:

- Surveilling and Monitoring Domestic Groups

- Strengthening and Enhancing National Cyber Defenses

- Controlling and Manipulating the Information Environment

- Foreign Intelligence Collection for National Security

- Commercial Gain or Enhancing Domestic Industry Growth

- Destroying or Disabling an Adversary’s Infrastructure and Capabilities

- Defining International Cyber Norms and Technical Standards.

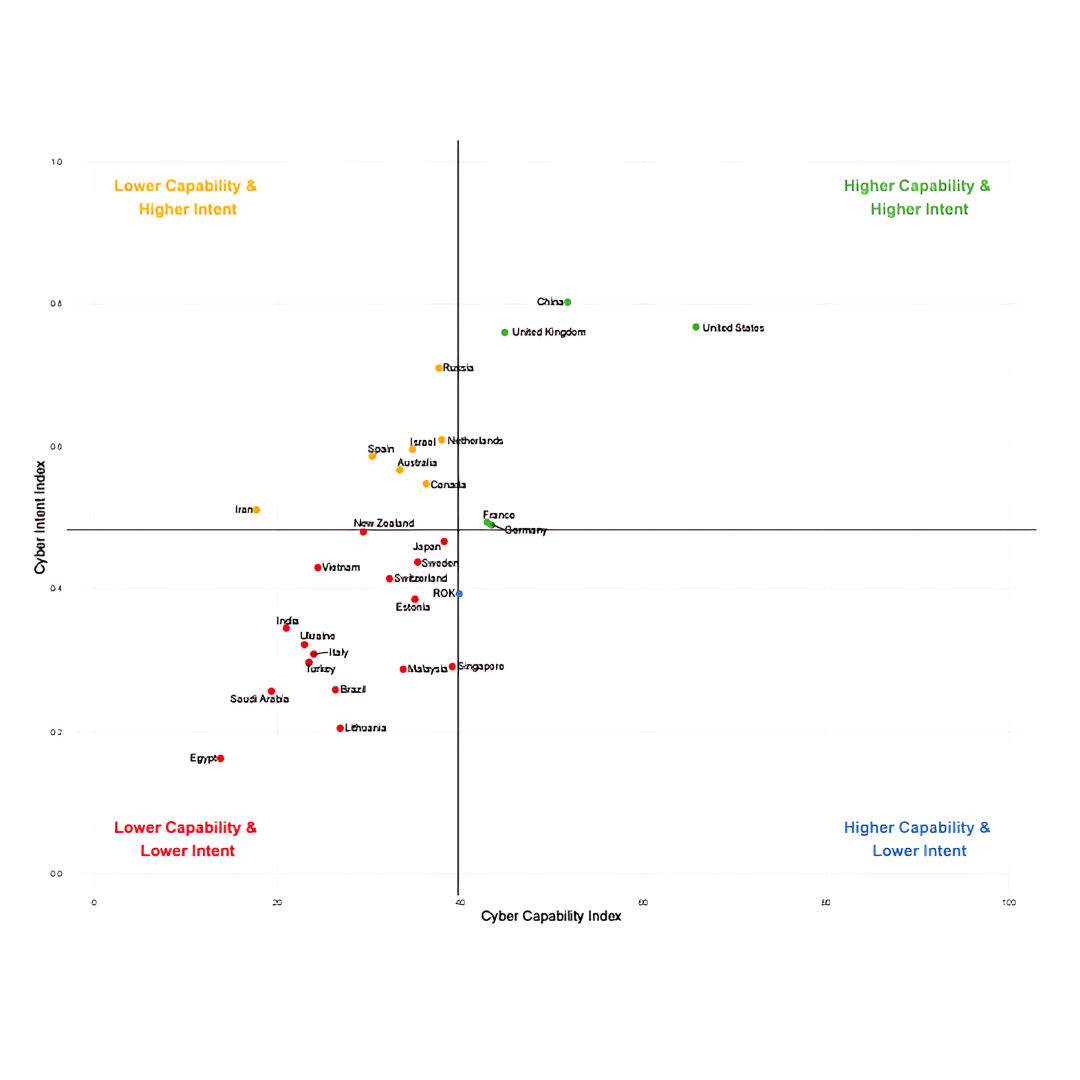

The current global cyber landscape categorizes countries into four groupings based on their higher/lower capabilities and higher/lower intent to achieve national objectives in the cyber domain. Figure 1 shows these groupings plotted on a graph.

Figure 1 – Plot of Cyber Power Rankings across Capability and Intent (Source – National Cyber Power Index 2020)

Major Cyber Conflicts

The 1999 Kosovo conflict was one of the major conflicts in which cyber operations were launched by warring parties for strategic advantages. However, several Western governments have been involved in offensive cyberespionage since the early 1990s. Prior to the American invasion of Iraq in 2003, the United States crippled the Iraqi government and military communication systems.

During the targeting of a suspected nuclear site in Syria’s Diaya-al-Sahar in 2007, Israel disabled and spoofed the Syrian Air Defence System. Stuxnet, which is regarded as the first high-profile cyber weapon, was jointly launched by the United States and Israel to specifically target Iran’s Natanz nuclear enrichment facility. To sabotage North Korean missile programs’ test launches, US President Barack Obama ordered cyber operations in early 2014. In May 2019, Israeli Defense Forces targeted a building in Gaza in an attempt to stop a suspected cyber operation by Hamas. This was the first instance in which to stop a cyber operation, a state military retaliated with physical violence.

Cyber Conflicts and Vulnerabilities

Despite the increasing integration of cyber operations in battlefields in the past two decades, no cyber operation has led to conflict escalation. Moreover, the majority does not consider cyber operations to cause an existential threat. This is due to the fact that states avoid crossing an implicit use-of-force threshold.

Scholars are skeptical about the future battlefields. However, some tentative conclusions and generalizations have been made. This allows us the opportunity to do scenario-building about the future.

The massive availability of quantum computing during the 2030s and 2040s will trigger advanced forms of cyber intrusions, rapid rolling out of newer digital platforms to avoid exploitation of vulnerabilities and escalation of cyber conflicts.

There are four possible scenarios, which are likely to shape the future of cybersecurity. The first scenario, also known as the ‘Gold Cage’ refers to states that will remain in a position of readiness with respect to adversaries and existing threats. Non-state actors will be the major threat in such a scenario. Secondly, in the ‘Protect Yourself’ scenario, cybersecurity is restricted to small thematic islands of security. The failure of the public sector to provide security has normalized cyber self-regulation and the use of cyber mercenaries.

Moreover, there is the presence of extensive cyber reconnaissance troops and cyber task forces. Likewise, within the gated communities ‘Cyber Darwinism’ projects a situation where there are small islands of high-level cybersecurity. Cyber warlords rule over individual territories along with gaining power by non-state and quasi-state actors. Lastly, in the ‘Cyber Oligarchy’ scenario, the concept of the state in dealing with cybersecurity-related matters is eroding. Hence, the private sector has taken lead in the enforcement of cybersecurity in accordance with the ‘laws of the jungle’.

The Future of Cyber Operations

In future, high military spending within militaries with respect to cyber operations is likely to negatively influence the economic performance of countries owing to increasing military-related expenditures.

To tackle such a situation, it is important that countries should focus on creating a favourable environment for hi-tech entrepreneurship. Coupled with cross-fertilization of military expertise, such an entrepreneurship ecosystem will contribute towards national economic growth.

A case in point is Israel where high military spending is positively contributing towards national economic growth. However, the underlying factor is that the governmental support of cybersecurity will highly determine the success of this approach.

Realizing the future need for a workforce proficient in various aspects of cybersecurity, it is important to impart cyber and STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) knowledge in the national security workforce. Experts have recommended that new promotion pathways should be created so that young officers who are fluent in new technologies are better able to familiarize themselves with the modern weapon systems and military doctrines which are rooted in current and future technological advancements. In the years to come, states will continue to view cyber operations as an attractive tool. This is due to greater independencies across networks, systems and infrastructure sectors.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of the South Asia Times.

![Ukrainian and Russian flags with soldier silhouettes representing ongoing conflict. [Image via Atlantic Council].](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/2022-02-09T000000Z_1319661209_MT1NURPHO000HXCNME_RTRMADP_3_UKRAINE-CONFLICT-STOCK-PICTURES-scaled-e1661353077377.jpg)