Afghanistan has been in a constant state of war for most of its known history but the last 50 years have been truly devastating for Afghanistan specifically and the region in general. A lot of misconceptions stemming both from a genuine lack of knowledge of Pak-Afghan history and deliberate propaganda can be seen flowing around. The most common being; Pakistan destroyed Afghanistan with proxy wars.

The Historical Roots of Conflict (1947-1979)

Most of these versions of the history of Pakistan’s “predatory” Afghan policy start from 1979, completely skipping the 1947–1979 part which was foundational in setting the direction of Pak-Afghan relations.

Let us go back even further to the mid-1940s when the Afghan Government started to plead and request the British Raj to transfer North-West-Frontier-Province (NWFP) or at least FATA to Afghanistan before leaving the region and granting freedom to Pakistan and India.

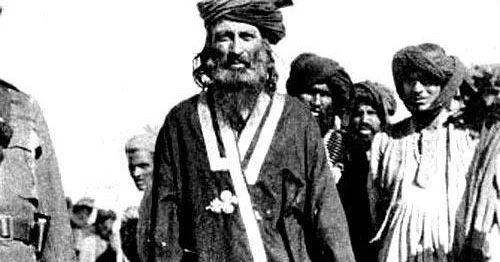

This demand was supported by local political leaders like Bacha Khan “The frontier Gandhi” and militant leaders like Faqir of ipi, Great Grandfather of TTP leader Hafiz Gul Bahadur. British did not heed the irredentist claims of the Afghan government due to their wider geo-strategic vision, with the ever-expansionist Soviet Union being a significant factor.

Many in the Western camp viewed Pakistan as a future ally in South Asia and as a containing force against creeping communist influence. NWFP after a referendum which was boycotted by the red-shirts of Bacha Khan was transferred to Pakistan in 1947. In a knee-jerk reaction, Faqir of Ipi announced a rebellion against Pakistan with the backing of the Afghan Government, and the Free State of Pashtunistan was announced in 1948–49.

The lack of widespread support for the Faqir of Ipi’s Pashtunistan Plan in the Tribal areas, coupled with the state’s focus on pressing issues such as the Kashmir conflict, refugee settlement, and the establishment of a new government, allowed the Waziristan rebellion to persist for several years. It wasn’t until 1953–54 that the Pakistani military initiated a significant response. This included heavy aerial bombardment of the Faqir of Ipi’s headquarters in Gurwek, marking the first military operation in Waziristan, ultimately resulting in his defeat.

Afghanistan also went the extra mile to stall Pakistan’s bid for membership in the United Nations in 1948.

Full-blown diplomatic offensive and occasional attacks on border posts continued from Afghanistan for the next two decades, with the biggest taking place in 1961 in Bajaur after which Pakistan Air Force bombed Afghan positions in Khost, and trade ties remained suspended for years between Pakistan and Afghanistan.

President Daud Khan’s irredentist dreams became his obsession and he diverted the complete economic resources of Afghanistan towards opposing Pakistan. During this time Pashtunistan and enmity with Pakistan were the cornerstones of Afghan foreign policy and domestic politics. In opposition to USA-allied Pakistan, Afghanistan also formally joined the Soviet camp and allowed Soviet military instructors and advisors in Afghanistan. A decision that proved fatal for Sardar Dawood Khan and Afghanistan a few years later.

Soviet Influence and the Rise of Afghan Islamists

The Afghan government in the 1970s carried out a bloody clampdown against Afghan Islamists of both traditional and Ikhwani streams. Thousand died and many were forced to find refuge in neighbouring Pakistan, which was reeling after the dismemberment of East Pakistan at that time. This was the first time when Pakistan reviewed its policy of half-hearted defensive measures against Afghanistan and adopted a more rigorous forward posture. This change of policy stemmed mainly from Pakistan’s fear of losing NWFP to another Bengal/East-Pakistan-type insurrection supported by regional rivals.

1974 was the year when Pakistan decided to support Afghan Islamist rebels to punish Dawood Khan for his Pashtunistan policy and Afghan rebels under the command of leaders like Gulbuddin Hikmatyar and Ahmad Shah Massoud carried out their first attacks in Panjshir and Ghazni.

Sardar Dawood’s rule came to a bloodied end in 1978 when he and his whole family were murdered by soviet soldiers and members of the Afghan communist, People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). Soviet Union’s 40th Army was deployed to prop up a pliant communist regime in Afghanistan.

![In 1974, Pakistan backed Afghan Islamist rebels to counter Dawood Khan's Pashtunistan policy. Rebels like Hikmatyar and Massoud initiated attacks [Image Credits: AP]](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/thediplomat-2020-07-17-6.webp)

Pakistan’s Pragmatic Response to the Soviet Invasion (1979-1989)

The Soviet Union, in its essence, was an expansionist political entity, with the export of communist revolution as its basic goal and it was very logical to assume that the Soviet Union was going to target Pakistan next. Moreover, the history of Soviet-Indian cooperation in the 1971 Indo-Pak war, and the Indo–Soviet Treaty of Peace, Friendship, and Cooperation of 1971, which played an important part in Soviet support for India in the 1971 war, also made Pakistani leaders nervous and wary of the looming danger of joint invasion from both the western and eastern borders.

Pakistan secured the involvement of the United States and other Western allies, significantly increasing its support for Afghan resistance groups fighting the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. Billions of dollars in financial aid and weaponry were funneled to the Afghan resistance through Pakistan, ultimately leading to the Soviet withdrawal in 1989.

Pakistan’s policy of supporting Afghan Islamists was more pragmatic than ideological and given the separatist movement in NWFP, the presence of nuclear-armed India on its eastern and Soviet armies on its western flank supporting Afghan resistance was probably the only viable option Pakistan had at that time.

The 1992 Peshawar Accords aimed to bring together disparate Afghan armed groups. Pakistan, through a combination of persuasion and pressure, attempted to broker a power-sharing agreement. However, this fragile peace proved short-lived. Regional powers saw an opportunity to exert influence by backing rival Afghan factions, further fueling the flames of conflict.

The battle for Kabul descended into a brutal civil war. Two main camps emerged: Jamiat-e-Islami led by Massoud and Rabbani, and Hizb-e-Islami Gulbuddin led by Hekmatyar. The ensuing struggle devastated Kabul, reducing parts of the city to rubble.

Pakistan, burdened by hosting millions of Afghan refugees and facing the consequences of a destabilized border, desperately sought an end to the bloodshed. In 1993, they brokered the Islamabad Accords, another attempt to establish a power-sharing arrangement. Unfortunately, this effort too proved unsuccessful, and the war in Kabul raged on.

Given the disastrous state of Afghanistan, Pakistan saw a glimmer of hope with the rise of the Taliban in the South. The Taliban’s swift military gains against the warring factions offered a potential path to ending the violence. In the hope of achieving regional stability, Pakistan made the strategic decision to support the Taliban.

Understanding Pakistan’s Afghan Policy

To truly understand Pakistan’s Afghan policy, we need to look beyond simplistic narratives and dig into the long, intertwined history of the two nations.

The unresolved border dispute, the Cold War’s influence that pushed Pakistan to back the Mujahideen against the Soviets, and the resulting power vacuum that birthed the Taliban – all these factors paint a complex picture.

Also Read: Afghanistan and Pakistan: The Road to Prosperity

Pakistan’s actions, while sometimes misguided, were largely driven by a desire for security in the face of a volatile Afghanistan and a looming Soviet threat. However, the unintended consequences of these interventions, coupled with the involvement of other regional powers with their agendas, significantly contributed to Afghanistan’s instability. Moving forward, a nuanced understanding of the past is vital. Regional cooperation, respect for Afghan self-determination, and addressing historical issues like the Durand Line – present time Pak-Afghan border dispute are all crucial for achieving lasting peace and stability in Afghanistan.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own. They do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of the South Asia Times.

Usama Khan, an IR graduate from Exeter, now resides in Lahore, teaching at a private university. His research focuses on South Asian history, politics, militancy, and civil conflicts.

![Pakistan's Afghan policy: People crossing into Pakistan from Afghanistan are making their way through the Friendship Gate in Chaman [Image via Reuters].](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/2021-08-15T143158Z_1093398639_RC2Q5P9W5VTP_RTRMADP_3_AFGHANISTAN-CONFLICT-PAKISTAN.webp)

Add a Comment