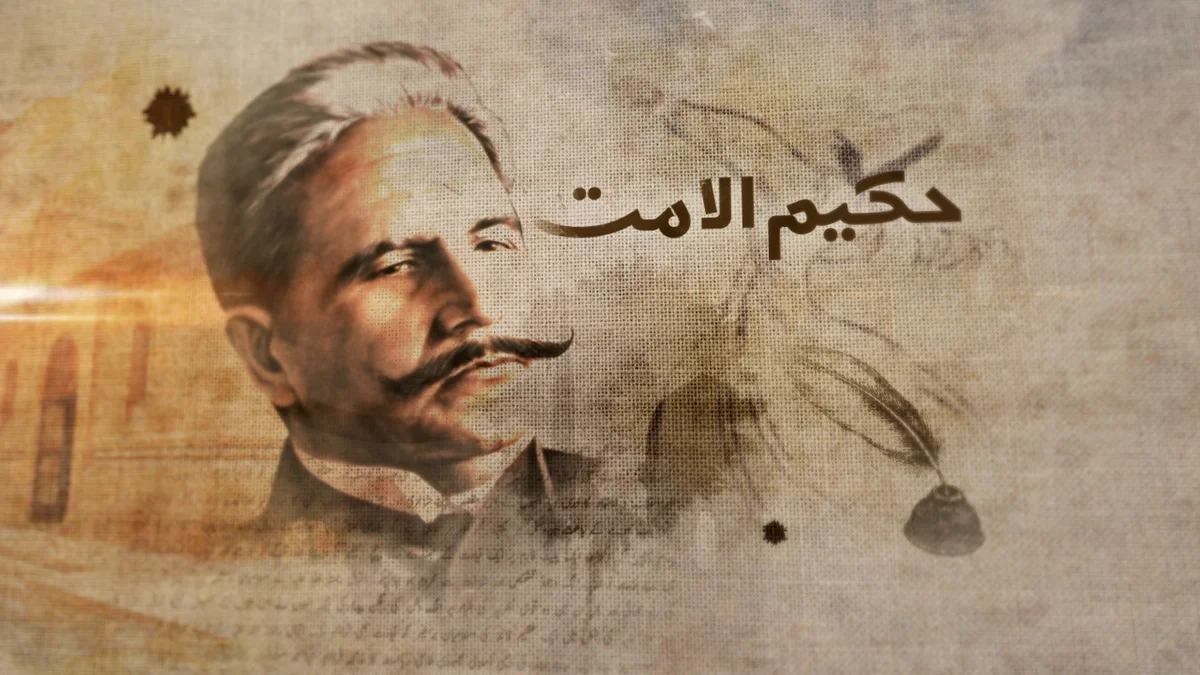

Allama Mohammed Iqbal (1877-1938), a poet and philosopher from the modernist trend of Islam is perhaps the most prominent Islamic visionary of the 20th century. Earlier in his life he was a committed Indian Nationalist with work romantically political. However, 1920s onwards Iqbal’s work became more reflective – as a philosopher-guide (nasih) to young Indian Muslims in an attempt to revitalize the fundamentals of Islam in the context of modern thought, and the challenges of the time. Mainly, the theological interpretation of God, Islam, the Universe, and Man’s purpose and place in connection with the Islamic fundamentals provided a whole new dimension to understanding religion as a code of life for the Muslims.

Islam to Iqbal was a philosophical ethos, more than a mere religion confined to the individual sphere. Thus, he spoke both in terms of the individual and the collective – framed in the concept of the Ummah.

For Iqbal, Man’s ultimate purpose on this earth was to shape it in Allah’s image (as His Vice-regent), from whose Infinite Ego comes Man’s own ego. In order to comprehend ‘God’s image’, Man must train and develop his ego to come into the closest contact with the Infinite Ego – working towards (what is also the quasi-Nietzschean) concept of the Perfect Man, embodied in the person of the Prophet Muhammad PBUH – who perfectly combines instinct/faith/love (ishq) with reason/science (aql), and can then manifest (show jalwat) his perfection into collective human action. Thus, in his writings, Iqbal emphasizes the building of one’s self (khudi), through various imagery – most prominently the soaring shaheen. Prayer, prominently Salah, is the best method towards the building and bettering of the ego.

The building of khudi is also why Iqbal advocated a return to ijtehad, rather than blind faith in taqlid.

Iqbal believed that the practice of ijtehad was a constant evolution for the better. Iqbal lamented the loss of ijtehad (legal advance) in the Islamic world through the early political triumph of conservative Ulama over the Mu’tazila, the perversion of Sufism into asceticism, and the destruction of Baghdad by the Mongols. He greatly admired personalities such as ibn Taymiyyah, Abd al Wahhab, Shah Waliullah, and Syed Ahmed Khan, and the modernists, who were trying to bring back such ijtehad, which contextualized Islamic law according to new challenges and discoveries, without retreating from the core spirit of Islam (quite apart from modern extremist takfiri interpretations of such individuals). Rejecting both the ‘narrow, medieval, aesthetic dogma’ of the contemporary Ulama, and the ‘mystic, monkish and ascetic’ trends which had developed in contemporary Sufism, Iqbal saw Islam as the birth of inductive intellect.

This dynamic world view of Islam and Islamic development leads to a rejection of static and deterministic trends in Islam by Iqbal, who in turn advocates the full immersion of Islam and Muslims into modernity. Though very critical of the moral decline of Western civilization (which had spurred the current modernity), he praises its scientific advancements. Western democracy though, Iqbal believed, was plutocratic (having no religious or moral moorings), and closely tied to greed in capitalism. The East, he thought, has remained lofty in its imagination whilst ignoring the real world; the West has reached such heights in this world. But the West has become ‘selfish, crafty and unscrupulous’ in pursuit of this – throttled by the coils of standalone reason – and the East is only adopting the superficial ‘glitter’ of the west without adopting the very institutions and energies of scientific creativity which have made them prosper and advance.

Rejecting both the ‘narrow, medieval, aesthetic dogma’ of the contemporary Ulama, and the ‘mystic, monkish and ascetic’ trends which had developed in contemporary Sufism, Iqbal saw Islam as the birth of inductive intellect.

Intuition therefore, is the higher form of intellect from which derives religion and faith. Human intellect is always outgrowing time, space, causality and moving towards intuition. Both are complimentary, not opposed. The prophetic message according to Iqbal has always been to re-establish moral contact between Man and God for the organization of human society, by regulating through morality the conduct and limits of humans, without which there would be oppression and slavery of man.

This emphasis on change, on action in support of thought, and of Islam and God as constantly evolving and always living (rather than merely as prima causa), places a heavy burden of introspection, reformation and revivalism on Indian Muslims. [Revivalism, to Iqbal, is not the same as the conservation of traditions and practices. For instance, Muslims should not look back to the glory of Baghdad, but forward to a new glory, responding to the challenges of the time]. To be able to move towards such lofty heights, they would need power, as love (religion) without power is insufficient for Iqbal. Therefore, he was of the firm opinion, especially after the breakdown of the Congress-Muslim league consensus, and the intensification of communalism, that Indian Muslims could not have the space or power to accomplish any of these missions whilst living as a minority in a united India.

After the failure of the Khilafat movement (1919-1924), and the abolition of the Ottoman Caliphate, Iqbal argued that although the Caliphate would always remain the ideal, it was not feasible at the time due to pressures from nationalism and the political weakness of the Muslims at large.

Iqbal’s version of pan-Islamism was not a narrow cultural or ethnic nationalism, neither a worldwide caliphate, but a kind of ‘Islamic league of nations’ – a multi-national neo-pan-Islamism.

His call in 1930, to the Muslim League session, for a separate and autonomous North-Western Muslim majority quasi-state (which later became a call for a fully independent Pakistan) can thus be understood as a stop-gap measure to allow Indian Muslims the space and power to understand their purpose, and eventually move towards Khilafat.

Iqbal’s concept of revivalism, is not the same as the conservation of traditions and practices; Muslims should not look back to the glory of Baghdad, but forward to a new glory, responding to the challenges of the time.

Iqbal joined the political arena rather late in his life (1927), but made a lasting impact on Indian Muslim political and social thought, most specifically in his encounters with the Quaid-e-Azam Mohammed Ali Jinnah (1876-1948).

Iqbal’s idea to dissociate politics from nationalism and to correlate it with religion and culture – means a rejection of secularism as well.

As per Iqbal’s vision, Islam is not only a religion, it is way of life – you cannot separate God and science (universe), spirit and matter, ‘church’ and state – these are organic to one another.

Further, Muslims are held together by belief in tawhid, and externalization of this in the form of Ummah (brotherhood), represented for example by the Ka’aba (the cognizable center), which symbolizes the bringing together of different races and cultures under one banner, in equality. Along with a rejection of Western democracy as plutocratic, populist, and based on racial inequality and exploitation of the weak, he saw in socialist ideas the modern interpretation of Islamic political ideas – a rejection of monarchical, hereditary and oppressive institutions, and racialism. But he saw in communism/Marxism the same lack of God as in capitalism; that communism is good in that it rejects the old injustices (theلا in لا إله إلا الله), but fails on the affirmation of truth (إلا الله) – providing little to offer as an alternative. Thus, both capitalist-imperialist democracy and revolutionary communism are insufficient for the Islamic state. The ideal Islamic state has to be based on Islam itself. Ideally, it is the Qur’anic state, which has never been realized yet apart from the time of the Prophet and the Khulafāʾu ar-Rāshidūn – a multi-national state of conscience, where all sovereignty lies in God, and all laws emanate from the full understanding of the Qur’an and its messages, and where the Caliph (not a personal ruler) understands his role as servant of Allah through service of the people. But this, as stated before, especially in the time he was writing, was politically not possible.

Thus, leaving this to be an ideal of the future, he adapted his theory of ‘cognizable center’ to apply to the specific problem of Muslim India. These Muslims needed their own cognizable center where they were in a majority (North-West). Therefore, despite his reservations against regionalism, the only tangible form of political expression that pan-Islamism could take was that of multi-nationalism, realizing itself in regional national states, working towards the ideal united Islamic state when future conditions would allow it.

In this vision was also the basis of the Two-Nation concept, where respective Muslim and Hindu identity is not based on ethnicity or language – it is based on emotional and psychological identity and solidarity; in this case, of religion, but not that alone – where thus the Muslims of India have always been a separate nation, with them being historically separate from the Hindus. Muslims have religio-political solidarity with the Middle East, Hindus with the Eastern experience.

According to Iqbal, historical efforts at emotionally homogenizing India as a whole nation have failed; such a ‘nation’ does not exist in India, where there are separate nations.

This was not without historical evidence, as seen by the failed efforts of Emperor Akbar and the poet Kabir, and even more recently, as efforts at Hindu-Muslim political solidarity had failed miserably. Therefore, this separateness in India has to be recognized and both nations must move forward on this basis. Ignoring it or trying to merge the two will only lead to inner tensions. Only by recognizing this fact can cooperation occur on the basis of interest of the two nations.

Allama Iqbal’s carefulness to not to attribute historical baggage to the future political solidarity of Indian Muslims. Iqbal sees Islam as conceived as the legal basis of this future state, where it would get rid of the stamp of ‘Arabian imperialism’ and mobilize law, education, and culture to bring them closer to the original spirit, in the context of modernity. This vision he strongly contrasts both with a Turkey-like secular state and a religious theocracy, which to him connotes fanaticism.

Finally, Iqbal also rejects ijma as the exclusive privilege of the Ulama. He extends the principle to the greater populace in the form of parliamentary democracy. This guarantees legitimacy – the participation of all, and greater input, as those from all walks of life and intellectual fields will contribute to interpret, and make the most appropriate sub-laws.

It is this revivalist theologically-inspired vision that, from 1936-37, Allama Iqbal presses upon Quaid-e-Azam M.A. Jinnah. Iqbal, in letters to the Quaid, pushed for the need for a separate Muslim state where they were in a majority. He also addressed the problem of League representation, and Muslim poverty, pushing for the League to move forward from only representing the interests of the upper classes to the masses. Iqbal and Jinnah both began their separate journeys as Indian nationalists, but ended as advocates of a separate homeland for Muslims. It was Iqbal who blazed a trail that Jinnah followed. Iqbal conceived the idea of Pakistan, Jinnah realised it.

![Ukrainian and Russian flags with soldier silhouettes representing ongoing conflict. [Image via Atlantic Council].](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/2022-02-09T000000Z_1319661209_MT1NURPHO000HXCNME_RTRMADP_3_UKRAINE-CONFLICT-STOCK-PICTURES-scaled-e1661353077377.jpg)