ROLE OF BENGAL IN THE HISTORY OF INDIA AND PAKISTAN

To understand the role of Bengal in the history of India and Pakistan in general and in the independence movement in particular, it has to be understood that Bengal’s role has been greatly influenced by its unique geography, demography, cultural shifts, and history. The province remained immune from central authority emanating from the center (Delhi, Agra, etc.) through most of the medieval and early modern periods.

A great turning point in Bengal’s history came with the disastrous battle of Plassey (1757), which destroyed Muslim hegemony in Bengal and gave way to British rule. Before Plassey, Muslims used to dominate the culture and politics of Bengal. This changed radically. The Hindus of Bengal rose quickly to grasp the opportunities offered under British rule, whereas Muslims lagged due to a combination of hubris, a false superiority complex, and systematic British policy. The role that Sir Syed played decades later for Muslims was performed by the likes of Ram Mohan Roy and Dwarkanath Tagore for Hindus in general and Bengali Hindus in particular.

HINDUS & MUSLIMS OF BENGAL

As a result, the Hindus of Bengal cemented their status as the leading native group in Bengal. They dominated Bengal’s economic, cultural, and educational life from the 19th century until 1947. The Muslims of Bengal produced heroes like Titumir and Dadu Mian, but they were ruthlessly suppressed by a combination of the British and Bengali Hindus. Consequently, the Muslims of Bengal (who constituted a majority of 57% of the population) practically became the underlings of the British. This situation created ample space for the Hindu exploitation of Muslims. The Bengali land aristocracy, educated elite, and intelligentsia became almost exclusively Hindu clubs. This was the state of affairs at the turn of the century.

PARTITION OF BENGAL

1905 marks a watershed year for both India and Bengal. This year, Bengal was partitioned into two provinces: the Hindu-majority West Bengal (plus Bihar and Orissa) with Calcutta as the capital, and the Muslim-majority East Bengal (plus Assam) with Dhaka as the capital. The Muslims of Bengal and Assam supported the partition as it meant more opportunities and government tutelage for the severely neglected Muslims of this area. But the Hindus were livid at this decision. They decried it as a manifestation of the “divide-and-rule” policy by the British. The British merely described this step as an administrative measure to ease the management of the huge united Bengal Presidency. Interestingly, the roles of Hindus and Muslims regarding Bengal’s partition would be reversed 42 years later, but more on that later.

The Hindus showed great skill and determination in their efforts to undo the partition of Bengal. Intellectuals like Rabindranath Tagore, moderates like Gokhale, and extremists like Tilak united in their opposition and confronted the British with a multi-pronged synergistic strategy. The former two categories lobbied the British politely but incessantly, whereas the latter category tried its hand at vigorous (sometimes violent) protests and acts of terrorism

Indian Muslims Before Partition

The Muslims didn’t even have an all-India political organization in 1905. A major reason for the establishment of the All-India Muslim League in 1906 was to defend Bengal’s partition. It wasn’t a coincidence that the first meeting of AIML was held in Dhaka and presided over by the Nawab of Dhaka. The Muslims knew that they weren’t strong enough to counter the Hindus alone, so they sought British tutelage. The British also made solemn promises to never undo the partition of Bengal.

Nevertheless, it was the Hindus who succeeded in bending the British to their will. The partition of Bengal was annulled in 1911. The Muslims were taught a lesson: in dealing with colonial masters, power and organization are much better tools than servile loyalty. As a mollifying gesture, the colonial government announced plans to build a university in Dhaka, but even that was too much for the Hindus, who firmly wanted the Muslim majority of Bengal trampled. A delegation of the “secular” Indian National Congress went to the viceroy to convince him that building a university in Dhaka would only be a waste of precious resources!

The saga of Bengal’s partition catalyzed Muslim separatism in India. In these years, many (including Iqbal) came to realize that the Muslims could not expect fair treatment from either the British or the Hindus. For some people who believed fervently in a future utopian Hindu-Muslim joint front against the British, like M. A. Jinnah, the anti-British sentiment among Muslims after their broken promises presented an opportunity to unite Muslims and Hindus as Indian nationalists against the British Raj. Ignoring the Hindu role in the Bengal saga, they declared that it was the British “divide-and-rule” policy that was the real culprit. They were going to get a taste of the Hindu mentality at the all-India level in a few years.

FIRST HALF OF THE 20TH CENTURY

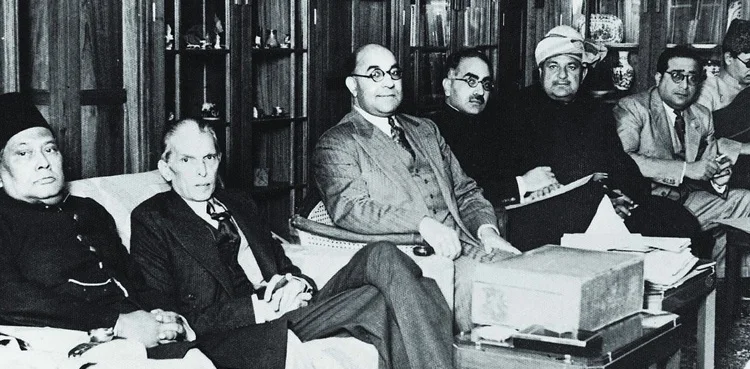

The first half of the 20th century brought a political awakening to the Bengali Muslims after a lull following the Faraizi movement. Three leaders signify 3 different streams here. A. K. Fazl-ul-Huq, H. S. Suhrawardy, and Khwaja Nazimuddin rose to become Prime Ministers of Bengal at various times under the British Raj. Fazl-ul-Huq represented the knee-jerk, erratic, irrational, wildly popular, and populist stream. He was well known for his frequent political somersaults. One day he would be an Islamic nationalist denouncing Bengali nationalism. The next year, he would come up with exactly the opposite notions. Then, he would go back the year after next. The only thread linking all his political somersaults seemed to be political opportunism (a notion supported by diverse historians from Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh like Rajmohan Gandhi, Badruddin Umar, and Safdar Mahmood, etc.). But Fazl-ul-Huq did a lot for the betterment of the common man in Bengal. And since it was the Muslims who were the poorest of the poor in Bengal, his politics brought a net benefit to Bengali Muslims.

Nazimuddin was the opposite of Fazl-ul Huq in many ways. His politics were conservative, pro-British, and pro-Islamic nationhood over Bengali nationalism. He was a Nawab who could never command or galvanize the crowd. But he was a loyal and reliable lieutenant to the Quaid-e-Azam in the battle for Pakistan.

Suhrawardy was the smartest of the trio. He also possessed a better vision and grasp of history. He was not erratic like Fazl ul Huq or quiescent like Nazimuddin. It was he who grasped very clearly the fact that the Muslims of Bengal had to join the struggle for Pakistan, for the sake of both Bengali and non-Bengali Muslims. Out of the 3, Suhrawardy rose the latest to prominence in the Pakistan movement but his impact was the most profound.

ELECTIONS IN BENGAL

In 1940, Fazl-ul-Huq (then Prime Minister of Bengal) presented the historic Lahore Resolution, which advocated the formation of independent Muslim states in the eastern and western zones of the subcontinent. But he soon fell out with the Muslim League and allied with the Congress and Hindu Mahasabha. Later, Quaid-e-Azam banned him from entering the AIML again. The tussle between Fazl ul Huq and the AIML led to a competition for Muslim votes between the former’s Krashak Paja Party and the AIML. In 1943, Fazl-ul-Huq’s government was dismissed by the British Governor, and Nazimuddin took over as PM. Nazimuddin’s rule was dependent on British goodwill, and little meaningful activity took place. In 1945, Nazimuddin’s government was replaced by the governor’s rule. Elections were scheduled for 1945–46. By this time, the Pakistan demand had become extremely popular all over Muslim India. Bengal was no exception. Quaid-e-Azam had finally and decisively become disillusioned with the Hindus after events like the Nehru Report (1928) and the obtuse behavior of Congress under J. N. Nehru after its victory in the 1937 elections. The Congress Ministries era (1937-39) and the accompanying Hindu chauvinism made it clear to the bulk of the Muslims that they had to unite otherwise Hindu majoritarian tyranny would gobble them up in a united India after the inevitable British withdrawal. Congress wanted to rule a united India but didn’t want to provide any meaningful rights or guarantees to the Muslim minority in a united India. Thus, it embarked on a strategy to split the Muslim vote by following a policy of neutrality or symbiosis against regional Muslim strongmen like Sikander Hayat and Khizar Hayat in Punjab and Fazl-ul-Huq in Bengal.

Against this backdrop, the election in Bengal for Muslim seats came down to a battle between Fazl-ul-Huq and the AIML, led by Suhrawardy. The charismatic Suhrawardy, armed with the popular dream of Pakistan, utterly defeated the erratic Fazl-ul-Huq, who appeared to be completely at sea. AIML won 113/119 Muslim seats in Bengal. AIML also secured huge victories in Punjab (73/82 Muslim seats), Sindh, Assam, and the Muslim minority provinces.

In April 1946, at the Delhi convention of AIML, Suhrawardy moved the resolution to amend the Lahore resolution and formulate the Muslim demand for a single Muslim state called Pakistan as opposed to the \”states\” mentioned in the original 1940 resolution. This was done to emphasize the unity and solidarity of Muslims behind the Pakistan demand. Bengal was especially important in this context, as it was widely interpreted that the original Lahore resolution meant the creation of a separate second Muslim state in Bengal or Assam. Thus, the amendment was necessary to avoid fissures within the Muslims at this stage because the establishment of Pakistan was by no means a forgone conclusion yet.

THE PARTITION 1947

This situation changed a year later. By April 1947, it was clear that Pakistan was coming into being. But it was also becoming evident now that Lord Mountbatten had acceded to Congress’s demand for the partition of Punjab and Bengal to keep the Muslim minority districts of these provinces inside India. Quaid-e-Azam reluctantly accepted this as the price for a sovereign Pakistan. The prospect of partition was even more distressing for Bengal than for Punjab. 95% of the industrial capacity of Bengal was confined to the Hindu majority areas in West Bengal (chiefly in Calcutta). AIML had advocated a plebiscite in Calcutta, which had a Muslim minority but whose scheduled castes were anti-Congress and might well have voted decisively for Pakistan, but the suggestion was vigorously opposed by Nehru and Vallabhai Patel of Congress. Lord Mountbatten’s well-known partiality towards Congress made it likely that a plebiscite in Calcutta would never be arranged and Calcutta would go with almost all the concentrated resources of Bengal to India. Only an impoverished East Bengal would come to Pakistan.

So, Suhrawardy came up with his United Bengal scheme at this point. He advocated for a third independent state, i.e., Bengal (with Assam included in all probability). Sarat Bose, the chief Congress leader in Bengal, also supported the United Bengal scheme. Bose’s brother Subhas Bose had been sidelined in the Congress despite being very popular through Gandhi’s backing of Nehru. Subhas had then gone on to create the Azad Hind army and join the Axis powers against the British in WW2. But the axis had been defeated, and Subhas died in 1946. His brother Sarat probably saw an independent Bengal as a way to thwart the Nehruvian hegemony in his homeland. Quaid-e-Azam supported Suhrawardy in his quest for a united Bengal despite the decision of the Delhi Convention in 1946. The reason was simple. Quaid thought that a Muslim-majority United Bengal would be a brotherly country for Pakistan and a subsidiary of Pakistan itself. Had he possessed an urge to “rule” at all costs, he would have insisted on partition and the inclusion of East Bengal in Pakistan. But Quaid-e-Azam had the best interest of Bengali Muslims at heart, and he knew that it was better to have an independent, united, democratic Bengal with a Muslim majority than to have an impoverished East Bengal as a part of Pakistan, which would be surrounded by hostile Indian territory and separated from the rest of Pakistan by a thousand miles.

The Hindu mentality can be gauged from Gandhi’s and Patel’s responses to the United Bengal Scheme. Gandhi insisted that in United Bengal, “every act of the government must carry with it the cooperation of at least two-thirds of the Hindu minority in the executive and the legislature.” Gandhi sought those safeguards for the Hindu minority in a united Bengal which he was never ready to extend to Muslims in a united India! Patel even went further. He wouldn’t even hear of a united Bengal. He thought that without Calcutta, East Bengal would be an unsustainable rump that would fall into India’s lap in a few months or years. Patel was also working very hard at that time to detach the NWFP (now KPK) from West Pakistan. His whole strategy was to make both wings of Pakistan stillborn. He envisioned that soon Pakistan would “beg” to be reincluded into the Indian union and then the dream of a united India/Akhand Bharat will be realized without giving any safeguards to the Muslims. Sarat Bose himself faced opposition from the Hindu MLAs of the Bengal Congress, whereas Suhrawardy was supported by the AIML. Ultimately, the united Bengal scheme was shelved due to Congress’s veto.

The United Bengal episode is ironic in the way that in 1905, the Muslims were the advocates of partition. The Hindus had even used terrorism as a tool to regain the unity of Bengal back then. Now, the shoe was on the other foot. Neither party can be termed a hypocrite, though. These stances and moves were all tactical adjustments within a cosmic and ancient conflict. Just like on the all-India scene, the primary tussle in Bengal was between Muslims and Hindus. Both sides had grievances; both didn’t trust each other, and hence, both wanted power at the expense of the other. Whether this main objective was supported by partition or otherwise didn’t matter for either side. In 1905, it was advantageous for Hindus to rule the roost in a united Bengal. With the advent of democracy by 1947, it was no longer possible for Hindus to dominate a united Bengal anymore unless that united Bengal be a part of a Hindu-majority India. Thus, the bulk of Bengali Hindus enthusiastically supported a partition. The Hindu leadership maliciously lobbied to rob East Bengal of Calcutta by scuttling the proposal of a fair plebiscite.

As a result, Pakistan received a populous but very impoverished and underdeveloped East Bengal, which was way behind West Pakistan. The roots of inter-wing disparity and rivalry were dug deep, and a factor of instability was injected into Pakistan even before it was born. After all, the cosmic conflict wouldn’t stop with partition. Like in 1905, Hindus again showed greater vision and took all measures to sow the seeds of future conflict within Pakistan. “Pakistan delenda est” was the Congress policy, and East Bengal was to be the Achilles heel of Pakistan, where suitable conditions for Pakistan’s destruction would be created. Unfortunately, the Hindus would find many unwitting partners in both East and West Pakistan for this dark enterprise.

READ MORE

Language Agitation in East Bengal

![Ukrainian and Russian flags with soldier silhouettes representing ongoing conflict. [Image via Atlantic Council].](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/2022-02-09T000000Z_1319661209_MT1NURPHO000HXCNME_RTRMADP_3_UKRAINE-CONFLICT-STOCK-PICTURES-scaled-e1661353077377.jpg)