Based on the thread initiated by Dr. Hassaan Bokhari (@shbokhari13), we are presenting the subject matter in its more expansive format. Enjoy reading!

Mujib had won an outright majority (160/300) in the elections, but he was still insecure and apprehensive. He feared that the military would somehow conspire to keep him out of power. Yahya had lost his political game, and now instead of a hung parliament, he had to deal with and transfer power to the Awami League, but he was still thinking of ways to thwart Mujib. He found a useful ally in the megalomaniac Bhutto. Bhutto had won a majority in the west wing (81/138). He hadn’t even put up a single candidate in East Pakistan. He was probably planning to use the army against Mujib after the elections to clear the way for himself to ascend to power. Otherwise, his strategy of only focusing on the minority wing while still loudly declaring his ambition to lead the whole country would appear nonsensical. Following the elections, all three felt insecure. Yahya suspected that if he obliged Mujib now, he would be toppled by the military junta. Bhutto and Mujib both thought that if they would even budge an inch from their pre-election rhetoric, their following might fragment, and they might lose their MNAs to another bidder or possibly the establishment. So, an already polarized atmosphere (due to the winning of the elections by each party in only one wing) became more charged. Bhutto fired the first salvos and bluntly declared that he was the sole representative of West Pakistan and that no government could form or function without his participation. The Awami League’s Tajuddin coldly reminded him that the Awami League commanded an absolute majority and had no need for Bhutto. Thus, Bhutto turned all his attention towards wooing the establishment through hopes and fears. After Yahya’s visit to Dhaka (in which an outward amiability was maintained), the deadlock over the six points and government formation remained unresolved. Yahya asked Mujib to soften his stance on the six points and take Bhutto on board. Mujib refused; he went straight to Larkana. Then Foreign Secretary Sultan Khan writes, “From sketchy accounts of this meeting, which are supported by subsequent events, Bhutto succeeded in convincing Yahya Khan that Mujib as prime minister would be a disaster for Pakistan.” He would abandon Kashmir, reduce military expenditure, raise an East Pakistan militia, transfer the capital to Dhaka, and generally dictate terms to West Pakistan. From then on, Bhutto frequently met Yahya Khan, and the more they met, the greater were the suspicions in East Pakistan. Yahya was already amenable to using Bhutto as a way to thwart Mujib. So, for the time being, both have renewed the “alliance” that was formed two years ago to depose Ayub Khan. At the end of January, Bhutto visited Mujib in Dhaka. Instead of negotiating constitutional issues like the Six Points, Bhutto only focused on the PPP’s participation in government. He brashly demanded 40% of the cabinet’s slots and the dual posts of deputy PM and foreign minister for himself. Mujib flatly refused. At this juncture, Bhutto shrewdly told Mujib that the military would never let a Bengali like him assume absolute executive power over all of Pakistan. Bhutto reiterated that only by making Bhutto a partner could Mujib thwart the military. Mujib remained unmoved but became deeply troubled.

Bhutto, the master politician, knew about the insecurities of both Yahya and Mujib. He wanted power at all costs and had swiftly recognized after the elections that he could only get power if Mujib and Yahya were to somehow finish each other off. So, on the one hand, he told Yahya that Mujib would curb the army, and on the other hand, he told Mujib that the army would never hand over power to him. The goodwill seen between Yahya and Mujib during the former’s visit to Dhaka evaporated. Mujib tried to contact the USA and India to inquire whether they would help him if he pursued secession. He received a positive response to the letter. In early February 1971, Mujib asked his cohorts Dr. Kamal Hossein and Tajuddin to draft a declaration of independence. The Mukti Bahini under Colonel Osmany was also alerted to the possibility of a conflict breaking out soon.

The situation was further aggravated when Mujib rudely turned down President Yahya’s invitation to visit West Pakistan in early February. A major complaint of Mujib at this point was that Yahya was reluctant to give a date for the new assembly session. He thought that Yahya was using delaying tactics so that he could buy off Awami League members and somehow erode its majority. But on February 13, 1971, Yahya declared that the National Assembly would meet in Dhaka on March 3, 1971. This brought some hope to Mujib, who again began thinking of becoming Pakistan’s PM and temporarily put his secessionist activities on hold. Yahya renewed his invitation to Mujib to visit West Pakistan. This time, Mujib seemed willing, but Bhutto was livid at this change in the state of affairs. In a fiery speech on February 17, he said that he wouldn’t go to Dhaka for the assembly session. He termed the Dhaka assembly hall a slaughterhouse. This incensed Mujib, who retorted that if Dhaka was a slaughterhouse for Bhutto, then all of West Pakistan was a slaughterhouse for him. Once again, he refused to come to West Pakistan. A leader who was the President-elect of Pakistan was refusing to even visit the wing where 47% of the country’s population lived and which encompassed about 80% of the total area of the country!

This fresh snub from Mujib again made Yahya deeply resentful and suspicious of Mujib. On February 22, in a meeting attended by all the imp generals, Yahya declared that he would indefinitely postpone the national assembly session. Governor of East Pakistan (Admiral Ahsan), and Chief Martial-Law Administrator of East Pakistan (General Yaqub) protested and said that such a decision would ultimately lead to civil war and Pakistan’s disintegration, but they were ridiculed and called cowards by some generals stationed safely in West Pakistan. During these turbulent times, Maj. Gen. Rao Farman Ali (who had been stationed in East Pakistan for a long time and had close ties with all Bengali politicians, including Mujib, as the head of the political affairs wing of the martial-law government in East Pakistan) proposed a novel approach. He advised in favor of allowing Mujib to take power because he could do no harm and would become the most unpopular man in East Pakistan within six months. He would endeavor to centralize power in his hands and would find the six points alien to his style and unworkable. Yahya emphatically rejected this scenario. Events from 1972 to 1975 (when Mujib was brutally murdered by his own men as a result of his corruption and despotism) proved Gen. Farman correct. But Yahya was more interested in clinging on to power, and thus he rejected all suggestions from the officers stationed in East Pakistan. Admiral Ahsan and Rao Farman Ali also met with Bhutto on February 25 and convinced him to back down for Pakistan’s sake. This appeal also fell on deaf ears. Bhutto, the socialist “expert”, ridiculed their fear of civil war and said that the Awami League was just a bourgeois party that could never conduct and sustain a civil war! On February 28, Bhutto demonstrated extreme belligerence once more. He threatened to break the legs of any PPP member who would dare to go to Dhaka. He also threatened any other MNAs from West Pakistan who would go to Dhaka. He also threatened Yahya that if he didn’t postpone the assembly session, he would launch another protest movement like the one against Ayub Khan, which would set the whole of West Pakistan from Khyber to Karachi ablaze! Yahya, unbeknownst to Bhutto, had already decided on a postponement. On February 28, he rejected Admiral Ahsan’s plea to reconsider. But he ordered Ahsan to meet Mujib that night and inform him beforehand of this decision (which was to be announced on national television on the 1st of March). Thus, Mujib came to know of Yahya’s decision a day before its announcement, which gave him time to organize a massive response the next day.

On March 1, when the announcement was made, the whole of Dhaka erupted in protest. Mujib and his cohorts (who knew of the decision in advance) acted as if they had received the surprise of their lives in public in order to further inflame the public. Awami League goons took over the streets and started terrorizing the non-Bengalis. An orgy of rape, loot, and murder enveloped East Pakistan. Sadly, the flames would keep on dancing for a long time.

Sheikh Mujib declared an ostensible “non-violent” civil disobedience/non-cooperation movement. In reality, he practically took over East Pakistan, whereas the martial-law authorities retreated to the cantonments. Even within the military installations, Bengali personnel (at least some of whom were Mujib loyalists) outnumbered the West Pakistanis. The Awami League’s “non-cooperation” movement gathered momentum. The party issued a slew of “directives” drafted by Tajuddin, Kamal Hossain, and party whip Amirul Islam. The directives covered a swath of issues, including the timing of strikes, a “no tax” campaign, the functioning of offices, banks, and other economic agencies, and the regulation of medical and other public services. Bureaucrats and police officials, judges, and business leaders all began to liaise with the Awami League. The central authority in East Pakistan collapsed completely. On March 3, Governor East Pakistan (Ahsan had been unceremoniously dismissed 3 days earlier), Gen. Yaqub pleaded with Yahya to immediately come to Dhaka and start negotiations to put an end to the instability, but Yahya refused. Disgusted with his callousness, Yaqub resigned with this prophetic remark: “I am convinced there is no military solution that can make sense in the present situation.” “I am consequently unable to accept the responsibility for implementing a mission, namely, a military solution, that would mean civil war and large-scale killings of unarmed civilians and would achieve no sane aim.” It would have disastrous consequences.”

General Yaqub was replaced by General Tikka Khan. On March 6, Yahya Khan blamed the Awami League for the political impasse and violence in East Pakistan in a speech. He announced that the National Assembly session will be held on March 25. At the mass rally at the Ramna Race Course on March 7, the day after Yahya’s speech, Mujib gave a masterful demonstration of oratorical skill. He satisfied the crowd with his toughest public stand against the west and the unshakeable commitment of his party to the emancipation of the Bengali people. He declared that he would not attend the National Assembly on March 25 unless four demands were met by the martial law authorities. First, martial law had to be abrogated; second, the troops had to be returned to their barracks; third, an inquiry had to be launched into shootings by the police and army during the period since the postponement of the Assembly; and fourth, power had to be immediately transferred to elected representatives. But contrary to the expectations of many, he didn’t declare independence. The commander of Pakistani army troops in East Pakistan, Gen. Khadim, had threatened him that if he did this, the army would respond with all its might. Maybe that played a part here, but it is unlikely. A more plausible reason is given by Mujib’s confidant, Dr. Kamal Hossain: “It was decided (by Sheikh Mujib) that the position to be taken should not be an explicit declaration of independence.” To exert pressure on Yahya, specific demands should be made and the movement sustained in support of these demands, with independence as its ultimate goal. Maybe Mujib still hadn’t given up on his dream of becoming the Prime Minister of Pakistan, but in my opinion, the explanation given by Kamal Hossein is most likely the correct one.

On March 14, Bhutto gave an impolite speech in which he revealed his true colors. This was the speech labeled with the headline “Idhar hum, Udhar tum” by the press. According to Sisson and Rose, “In an address at a public meeting on March 14, much to the alarm of most other West Pakistani leaders, Bhutto announced that if there were to be a transfer of power before the framing of the constitution, it must be transferred to the Awami League in the east and to the People’s Party in the west, after which the majority parties would have to come to a consensus on the constitution.” Dr. Safdar Mehmood mentioned in his book “Pakistan Divided” that “it is, however, relevant to quote here another statement of Bhutto that Sheikh Mujib ur Rehman could become Prime Minister of East Pakistan and he would take over as Prime Minister of West Pakistan in a confederated scheme of things.”

If secessionism is enough to brand a person a traitor, then now Bhutto was also a traitor!

On March 15, Yahya belatedly arrived for talks with Mujib. Mujib welcomed him as “Bangladesh’s guest” and “graciously” removed armed Awami League posts that blocked the road between the Dhaka cantonment and the airport. From the start, the negotiations didn’t show much promise, as Mujib was now bent on having a confederation, i.e., two separate states. On March 17, Yahya Khan ordered Tikka Khan to start planning a military operation against the secessionists. Major General Khadim Raja (the GOC of the sole army division in East Pakistan) and Maj. Gen. Rao Farman Ali formulated the plan on March 18 and named it “Operation Searchlight.” The situation changed a bit during that day, though, and it seemed that some workable compromise might be reached between Mujib and Yahya. Yahya also called his legal experts from West Pakistan to negotiate the constitutional issue with Mujib’s advisors. But Bhutto again became incensed at this and released another belligerent statement. Yahya duly invited him to participate in the negotiating process by inviting him to Dhaka, much to the chagrin of Mujib. Bhutto’s arrival again sowed doubts in Mujib’s mind, and he hardened his stance. Bhutto also played no constructive role in Dhaka and just raised more issues, which complicated the negotiations even more.

March 23 proved to be a momentous day. 31 years earlier on this date, the resolution demanding Pakistan’s creation was put forward by Bengali politicians. In 1971, this date marked the end of a united Pakistan. According to G. W. Chaudhry, “On March 23, 1971, not only was the Pakistani flag not hoisted, it was burned and insulted, and the flag of Bangladesh flew everywhere.” Mujib took the salute at a march-past composed of Bengali paramilitary units at his residence; the flag of Bangladesh was hoisted with great pomp and grandeur as if the new nation of Bangladesh were already established. Mujib’s public statements were equally provocative and unfortunate. On this day, during negotiations, both the Awami League legal team and the political leaders told their West Pakistan counterparts that they wouldn’t accept anything less than a confederation. The West Pakistan team responded that this option was never even considered and that if the Awami League was adamant about this demand, future negotiations would be futile. They accused the Awami League of bad faith and deliberate deceptions; they were under the impression that the Awami League only wanted provincial autonomy, not secession. Nevertheless, Mujib refused to budge, and this stance was reiterated by his chief lieutenant Tajuddin on March 24, during what proved to be the last meeting between the two sides.

Yahya Khan ordered General Tikka Khan to launch Operation Searchlight on the night of March 25, 1971. Instead of commanding his troops in a civil war of his own making, he chose to flee to West Pakistan before the start of hostilities. Yahya Khan left Dhaka as the sun was setting on East Pakistan on the fateful evening of March 25. There was to be no dawn after this long, dark night that began that evening.

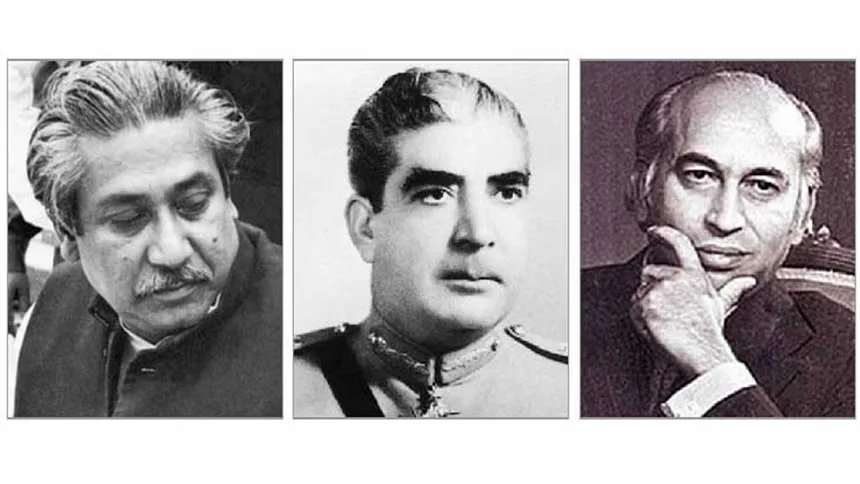

If the performance of the terrible trio of Yahya, Mujib, and Bhutto is analyzed during the period from December 1970 to March 1971, we can appreciate the massive villainy and incompetence at play.

Yahya and the generals underestimated the Bengalis and didn’t take adequate notice of the Indian threat. Their stupidity led to fratricide, defeat, and surrender.

Mujib underestimated the army and foolishly hoped that his ragtag militia would oust the Pakistan Army swiftly if push came to shove. He perceived the negotiations and concessions as weaknesses and thought that he might get away with a peaceful secession. His stupidity resulted in widespread destruction in East Pakistan.

Bhutto wanted a confrontation between the Awami League and the Pakistan Army. He knew that in the event of an agreement, Mujib might become prime minister. Even in the case of a peaceful separation, the army might blame him and refuse to relinquish office or power. He wanted Mujib destroyed and the army discredited. He got what he wanted.

Read more

Military Operation, Civil War, and Indian Meddling

Also See: ‘Last Nail in the Coffin?’ Modi Loses Elections to Mamta Banerjee in West Bengal