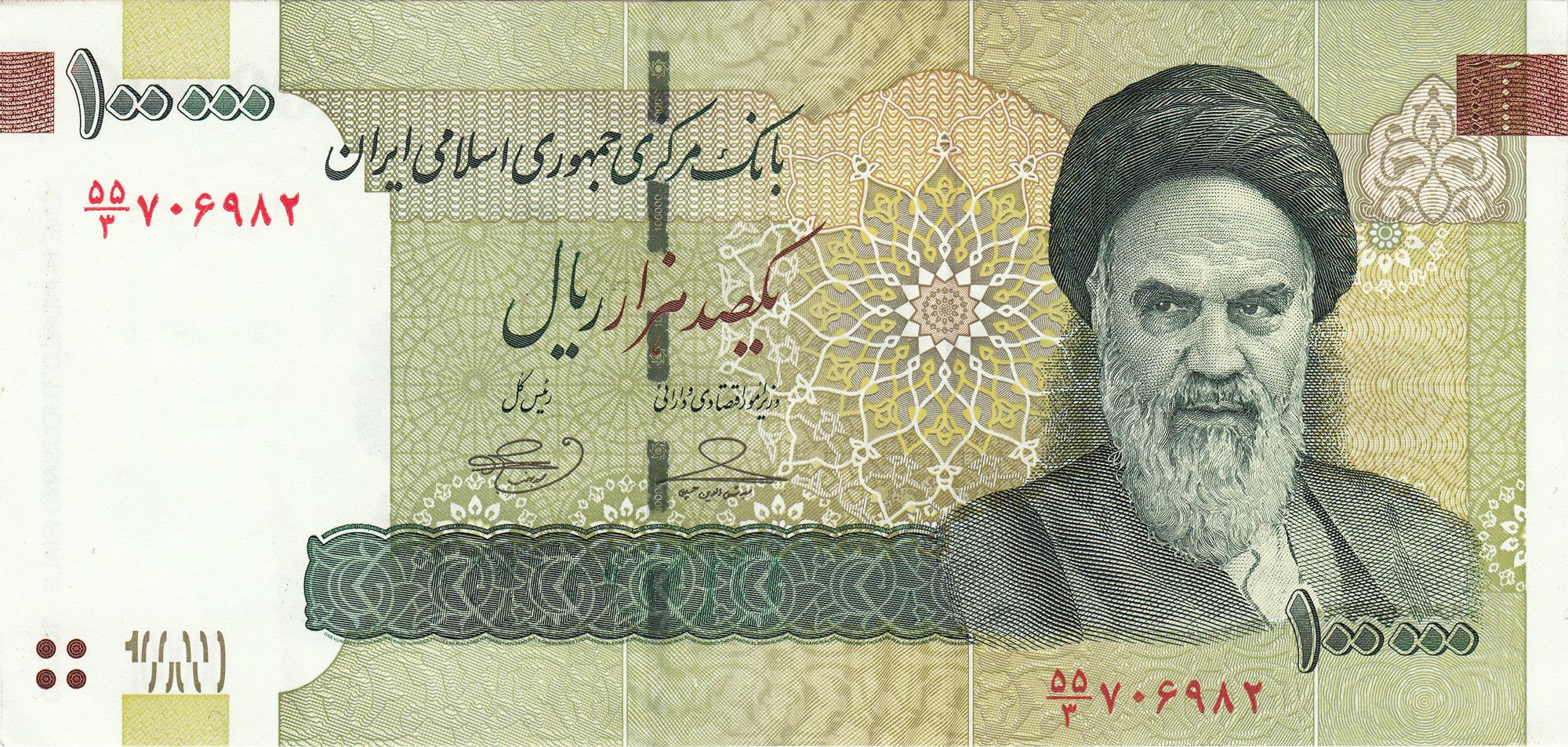

In the opening weeks of 2026, the global financial community watched with a sense of grim inevitability as the Iranian Rial (IRR) breached the psychological barrier of 1.4 million per U.S. Dollar on the open market. While currency volatility has been a hallmark of the Iranian economy for decades, this specific plunge followed the June 2025 escalation of regional hostilities and the subsequent snapback of comprehensive United Nations sanctions.

A currency is more than a medium of exchange. It is a barometer of state capacity and a quantification of international trust. When a currency crashes suddenly, it signals that the state’s ability to project power, maintain the social contract, and interface with the global order has reached a terminal point of friction. The Iranian crisis serves as a contemporary laboratory for understanding how long-term institutional decay and geopolitical isolation eventually manifest as a total monetary breakdown.

To analyze why a currency evaporates in value overnight, we must look beyond simple supply and demand. In political economy, we often categorize these events through generational models of currency crises.

First-generation models, pioneered by Paul Krugman, suggest that crashes occur when a government’s domestic policy (excessive spending) is fundamentally at odds with its exchange rate policy. When a central bank exhausts its foreign reserves trying to defend an overvalued rate, the peg snaps, leading to a violent devaluation.

Second-generation models focus on the self-fulfilling prophecy of market expectations. Even if a country’s fundamentals are manageable, if investors believe a crash is coming, they flee simultaneously. This capital flight forces the very collapse they feared. These models illustrate that a currency is a proxy for sovereignty. In a globalized financial order, a state that cannot maintain a stable unit of account loses its ability to engage in soft power, as its economic weakness becomes a strategic liability that adversaries can exploit.

Major Precedents in Recent Decades

The Iranian experience, while unique in its intensity, follows a historical pattern of sudden stops in capital flows.

The 1994 Mexican Peso Crisis, often called the Tequila Crisis, demonstrated the danger of relying on short-term hot money to fund a deficit. When the US raised interest rates, capital fled Mexico, causing the Peso to lose half its value in weeks. This forced a massive international bailout led by the IMF, highlighting how currency crashes often necessitate a surrender of economic autonomy to international lenders.

The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis shifted the focus to contagion. What began as a localized devaluation of the Thai Baht quickly dismantled the Tiger Economies of Indonesia and South Korea. This proved that in a connected world, a currency crash in one state can trigger a cascade of failures across an entire region, regardless of individual state merit.

More recently, the 2022 Russian Ruble volatility following the invasion of Ukraine offered a good example in fortress economics. While the Ruble initially cratered, the Russian Central Bank used draconian capital controls and energy-export requirements to artificially stabilize the currency. However, as Iran’s history shows, such stabilization is often a mask for long-term stagnation.

History also teaches us that when currency crashes, the existing political order usually follows. The most infamous example remains the Weimar Republic in the 1920s. Hyperinflation did not just destroy savings, it destroyed the legitimacy of liberal democracy in Germany, creating the vacuum into which Nazism stepped.

In 1998, the Russian financial crisis led to the humiliation of the Yeltsin era. The crash wiped out the emerging middle class and paved the way for a more centralized, security-focused leadership under Vladimir Putin, who promised stability over market freedom. The currency crash was the catalyst for a fundamental shift in Russia’s internal and external posture.

Similarly, the precursors to the 2011 Arab Spring were deeply rooted in currency-driven food inflation. In Egypt and Tunisia, the inability of the state to manage the price of imported wheat (priced in USD) meant that as the local currency weakened, the cost of bread became unbearable. The “bread riots” that followed demonstrated that a currency crash is the fastest way to break the social contract between an autocrat and the populace.

The Structural Erosion of the Iranian Economy

The current 1.4 million Rial-to-Dollar exchange rate is not the result of a single bad week of trading. It is the culmination of multiple distinct, overlapping structural failures.

For over forty years, Iran has faced varying degrees of economic isolation. However, the maximum pressure campaign initiated in 2018, combined with the 2025 snapback of UN sanctions, has effectively disconnected the Iranian banking sector from the SWIFT network. Without the ability to repatriate oil revenues or access to frozen assets overseas, the Central Bank of Iran (CBI) has lost its primary tool for intervention.

A critical factor often overlooked by Western economists is the role of the bonyads (parastatal foundations) and the economic wings of the Revolutionary Guard (IRGC). These entities, such as the Mostazafan Foundation (Foundation of the Oppressed) and Setad, control upwards of 30 to 50 percent of the GDP but operate with little to no oversight.

Because they have priority access to subsidized exchange rates through state-linked banks like Bank Pasargad and Bank Parsian, they can engage in currency arbitrage. They buy cheap dollars from the state at the Nima rate and sell them at the open market rate of 1.4 million IRR to fund their regional activities. This creates a parasitic loop where the state’s efforts to help the poor through subsidies actually enrich the security apparatus while draining the national treasury.

The Iranian leadership has long championed the Resistance Economy, an autarkic model intended to make the country immune to sanctions. However, this has resulted in a failure to diversify away from hydrocarbons. When regional hostilities in 2025 led to the disruption of shipping in the Persian Gulf, Iran’s only source of hard currency was throttled. The government’s response, printing money to cover the deficit, led to a classic liquidity trap where more money was chasing fewer goods, sending the Rial into a tailspin.

The Human and Geopolitical Cost

The short-term impact of the January 2026 crash is immediate and visible. The bazaar strikes that paralyzed Tehran and Isfahan in late 2025 were a direct reaction to the Rial’s volatility. Merchants could no longer price goods because the value of their currency was changing by the hour. For the average Iranian citizen, the crash meant the total evaporation of life savings and a 70 percent increase in the cost of imported medicines and basic foodstuffs.

Inflation has now breached the 45 percent mark, and for many in the lower middle class, burden has become unbearable. The sudden introduction of a third tier for gasoline pricing in December 2025, reaching 50,000 rials per liter for excess consumption, served as the final spark for cross-class protests. Unlike previous movements, these demonstrations have seen a rare coalition of industrial workers, teachers, and merchants, all united by a single grievance: the disappearance of their purchasing power.

In the long term, the crash accelerates atrophy. The brain drain of Iran’s educated youth is no longer just about political change, it is about economic survival. When a software engineer in Tehran earns the equivalent of 80 dollars a month due to devaluation, the incentive to stay vanishes. SMEs (Small and Medium Enterprises) that lack the political connections of the Bonyads are being wiped out, further consolidating the economy into the hands of the military-industrial complex.

The breach of the 1.4 million Rial threshold marks the beginning of a new, more volatile chapter for the Iranian state. For policy analysts, the trajectory suggests that temporary measures, like the reintroduction of a coupon system for essential goods or crackdowns on street-level money changers, will remain largely cosmetic. Such interventions fail to address the fundamental evaporation of trust in the state’s economic stewardship.

A currency is, at its core, a social contract. It is a silent promise that the labor an individual contributes today will retain its value tomorrow. When that promise is broken through a combination of external pressure and internal corruption, the state loses its most fundamental link to its people.