Militant violence in Afghanistan and Pakistan is not driven by weaponry alone but by struggles over legitimacy, authority, and narrative control. Over a year after the Taliban’s consolidation of power in August 2021, militant violence in this area has increased in intensity and has undergone a dramatic change in nature and intent. At the epicenter of this change are the Islamic State in Khorasan Province (ISKP), a consequence of a rift in an existing larger jihadist ecosystem that has long been occupied by the Taliban in Afghanistan and its affiliates in Pakistan in the form of Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). ISKP and these two militant groups are actually splinter groups in a larger militant family that has been defined by shared battlefields, shared leadership, and shared militant operatives.

This article argues that any discussion on post-2021 militancy with regard to South Asia must centrally feature ISKP and its ideological intentions, leadership dynamics, recruitment mechanisms, and rivalry with the Taliban-TTP network. By exploring direct lines of descent between various militant groups, changes in the post-Taliban takeover pattern of security dynamics, and narratives of threat manipulation, this article explains not only why terrorism has remained a means of violence and leverage but why peace has remained elusive without a joint counterterrorism platform between Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Historical Origins of ISKP, the Taliban, and TTP

The Afghan Taliban, ISKP, and Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan originated from closely interlinked militant groups that had been formed over several decades of conflict that ravaged Afghanistan as well as Pakistan. The Afghan Taliban was a Pashtun movement that had been formed in the mid-1990s with the aim of imposing its brand of Islamic rules within the territorial confines of Afghanistan despite being ideologically aligned to the jihadist movement.

The TTP came into prominence in 2007 when it was formed as an alliance between Pakistani militant groups fighting in the former Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) in the Afghanistan-Pakistan border regions. Though, this was inspired by the Afghan jihad, it turned the guns inward and focussed on the Pakistani state in the wake of the Pakistani government’s post- 9/11 alignment with the United States. Over the years, the TTP built an efficient command and control system with recruits, legitimacy, and havens in the immediate neighborhood of the Afghan Taliban.

The emergence of ISKP in 2014-2015 thus represented a pivotal point of fragmentation within this network. Contrary to its representation as a foreign intervention, ISKP actually came into existence as a result of splinter group defections from the TTP, Afghan Taliban, and al-Qa‘ida affiliates. In January 2015, Hafiz Saeed Khan, a top-tier TTP commander for Orakzai Agency, was chosen as the inaugural emir for ISKP. Khan Saeed’s standing in the TTP was pivotal; he was seen as a leading candidate for leadership following the assassination of Hakimullah Mehsud and came second only to Fazlullah for control of the TTP leadership.

Hafiz Saeed Khan formally split from the TTP in October 2014, along with four other senior commanders and the spokesperson of the group, Shahidullah Shahid, swearing allegiance to the Islamic State. The list of TTP commanders who defected to ISKP includes Hafiz Quran Daulat (then the TTP chief in Kurram Agency), Gul Zaman (then the TTP chief in Khyber Agency), Mufti Hassan (then the TTP chief in Peshawar), and Khalid Mansoor (then the TTP chief in Hangu district). All of these individuals in total commanded militant networks in a crucial arc running from Peshawar to the Khyber Pass and made up a significant loss to the TTP and simultaneous gain to ISKP, which has highly permeable lines in the militant environment.

Additionally, continuity of leadership remained within ISKP even after its emergence. After the ISKP emir, Aslam Farooqi, was arrested in 2020, the Islamic State nominated Shahab al-Muhajir as the leader of ISKP. al-Muhajir, former ISKP urban operation planner in Kabul, is said to have been a mid-level commander in the Haqqani Network, an important faction of the Taliban. This further emphasizes that the channels of leadership within the Taliban, Haqqani, TTP, and ISKP are fluid, and this fluidity is determined by administrative transfers and not ideological lines.

ISKP Ideology and the Logic of Militant Competition

ISKP’s uniqueness does not only reside in its organizational lineage but in its ideological absolutism too. ISKP functions as a wilayah (province) of the Islamic State, and as such, it promotes the IS vision of a transnational caliphate that spans the territory of ancient Khorasan, the territory includes areas in today’s Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. ISKP promotes its vision based on the motto “baqiya wa tatamaddad” (remaining and expanding), urging all Muslim immigrants from all over the globe to move and fight in defense of a “pure” Islamic state ruled by sharia law.

Such a fixed ideological position is embedded within the Islamic State’s doctrine, particularly the 2016 beliefs document “Aqidah wa Manhaj al‑Dawlah al‑Islamiah fi al‑Takfir.” Takfir refers to the overlapping concepts of both labeling other Muslims as kafirs (unbelievers) and positing the execution of those who do not adhere to the group’s own adaptation of the religion’s more radical interpretations of the sharia. As a result, the group can disqualify other, more regional

jihadist groups, specifically the Taliban, for their nationalist ideologies, for the regional focus, and for negotiating with other global actors. Ideology as belief and as recruiting technique: The ISKP has maintained its struggle with the Taliban as one between “true jihad” and insurgent pragmatism. Analytical judgments have also indicated the mid-level ranks of the ISKP to include a substantial number of former Taliban militants, with some leaders belonging to Lashkar-e- Taiba and Al-Qa‘ida within the Indian Subcontinent, showing the capacity of the ISKP to absorb dissatisfied militants across the ideological divide, with its ideological pronouncements thus becoming a recruiting badge for militants searching for legitimacy and theocratic latitude to maneuver.

Transnational Recruitment Dynamics: Indians, Bangladeshis, Central Asians, and Beyond

Of all the recent developments within ISKP, perhaps the most striking has been its increasingly transnational recruitment footprint, reinforcing the group’s claim of a global jihadist identity that distinctively sets it apart from the more typical nationalist-sounding orientations of the Taliban and the TTP. Indeed, the foreign fighter intake into the organization includes a variety of nationalities, underpinning its ability to recruit outside the immediate Afghan–Pakistan conflict environment.

In March 2022, ISKP’s flagship publication Voice of Khurasan spotlighted the case of Najeeb al‑Hindi–a recruit from Kerala in southern India-revealing the group’s sustained interest in attracting Indian fighters. The decision to feature an Indian figure within its principal propaganda outlet reflects ISKP’s intent to position itself as a destination for non‑Afghan fighters, rather than a peripheral insurgent entity. Indian recruits like Najeeb al‑Hindi, Abu Khalid al‑Hindi, and Abu Rawaha al‑Hindi have served as active combatants and, in some cases, are chosen as suicide bombers in key operations, such as the high‑profile attack on Jalalabad prison on 2 August 2020, where Abu Rawaha al‑Hindi-a medical doctor by training-played a key role.

The implications thereof are substantive. An expanding Indian recruitment pipeline internationalizes the threat posed by ISKP but also creates potential security spillovers within India, Afghanistan, and beyond; hence, regional cooperation and intelligence sharing become increasingly important.

ISKP’s foreign fighter intake is not limited to India. Afghan officials have reported detaining hundreds of foreign nationals associated with ISKP. According to government records, 408 ISKP members (of which 173 were women and children) were detained, while the various nationalities

included Pakistan (299), Uzbekistan (37), China (16), Tajikistan (13), Kyrgyzstan (12), Russia (5),

Jordan (5), Indonesia (5), India (4), Iran (4), Turkey (3), Bangladesh (2), and the Maldives (2). The group has also drawn in recruits from Bangladesh. Afghan officials detained a suspected high- ranking ISKP leader, Mohammad Tanvir, in northern Afghanistan. Tanvir studied engineering at Bangladesh University and was wanted by Dhaka for his purported role in a failed 2017 plan to bomb a high‑profile event hosting Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. Reports suggest that Tanvir was in contact with a Bangladeshi operative who died in a botched suicide attack in Dhaka in 2017, reflecting ISKP’s ability to mobilize militants from South Asia’s heavily populated states. These dynamics of recruitment greatly expand ISKP’s sphere of operations and internationalize its appeal, sharply contrasting with the Taliban’s more territorial objectives and the TTP’s insurgency focused within national borders.

Post‑2021 Security Shifts and Regional Dynamics

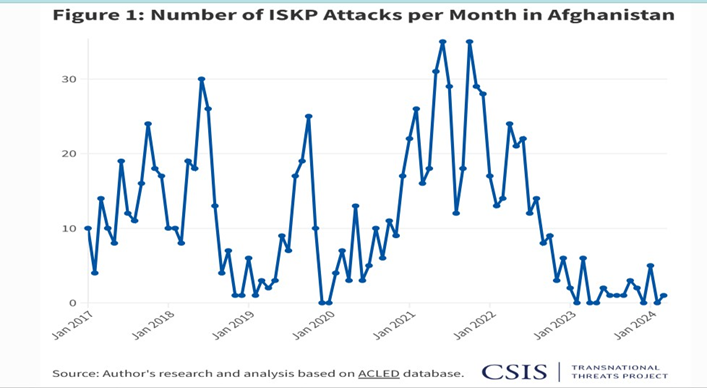

The emergence of the Taliban in August 2021 marked a significant shift in the security dynamics of the region as the insurgent group became the ruling body responsible for protecting territory and terrorism-related obligations. Following the Taliban’s consolidation of power, the Islamic State in Khorasan Province (ISKP) increased their attack levels in Afghanistan to the highest recorded levels since their initial appearance. While ISKP’s attack levels did slow following Taliban counterterrorism efforts, the ISKP was able to adjust through decentralization, diversification, and the recruitment of members, covering the eastern, northern, and other provinces.

Crucially, the increased number of foreign fighters within ISKP’s ranks has increased the threat level from a local conflict scenario to a higher level. UN Security Council Monitoring Team reports have shown that ISKP has been able to absorb foreign fighters, retain training camps, and retain mobile units that are able to carry out cross-border activities. It is clear that ISKP is still attracting fighters from different nations despite the efforts of the Taliban’s security operation tactics to suppress them.

In Pakistan, whereas the current violence has been under the operational control of TTP, it has been facilitated by the larger ISKP-Taliban militant environment. There were 207 terror attacks in 2021 in Pakistan, a 42% rise from 2020. Terror attacks increased in 2022 but further escalated in 2023 to 306 incidents, accompanied by 23 suicide attacks that took 693 lives; in excess of 80% of them were killed by either TTP or its allies. ISKP’s activity decreased in terror attacks in Pakistan but acted as a force that altered militant activities and triggered desertion or fragmentation with escalated activities.

The reports of the UNSC monitoring team have also brought out that militant groups such as TTP, ISKP, and AQ-linked groups function with greater freedom under Taliban ruling, using their territory for training, planning, and operations in Afghanistan and beyond. It has also been mentioned in this regard that TTP militants, estimated to be several thousand, remain one of the main sources of contention between Kabul and Islamabad, with efforts of the Taliban, according to Islamabad, facilitating cross-border attacks.

Strategic Leverage: ISKP as Narrative, Buffer, and Diplomatic Tool

Since 2021, the Afghan Taliban have directed their public diplomacy by designating the ISKP as the primary terrorist threat, emphasizing specific counterterrorism actions as indicators of adherence to international expectations. This framing obscures a fundamental pattern of intentional selective enforcement. UNSC monitoring reports consistently show that the leadership, training facilities, and logistical centers of the TTP persist in functioning from Afghan provinces like Kunar, Nangarhar, Khost, Paktika, and Paktia, where the group executes intricate cross-border assaults

The Taliban’s tolerance of the TTP is based on ideological affinity, a shared Pashtun identity, and battlefield cooperation that has lasted for decades. By providing operational space to the TTP, the Taliban reduce the risk of large-scale defections to ISKP and restrict ISKP’s recruitment pool. In return, ISKP remains a convenient enemy for the Taliban-one that allows it to claim counterterrorism legitimacy while leaving allied militant networks intact, which are important for regime stability. This approach outsources insecurity to Pakistan, complicates bilateral relations between the two nations, and entrenches domestic distrust.

That dynamic was underlined by the March 26, 2024 attack near Besham, which killed five Chinese nationals and a Pakistani driver. Pakistan attributed the operation to militants operating in the TTP ecosystem from Afghan bases. The Taliban denied responsibility and accused Pakistan

of politicizing terrorism. Such responses point to how ISKP serves as a political shield, defraying accountability while constraining Pakistan’s strategic options.

Pakistan’s Strategic Constraints amid the ISKP–TTP Nexus

Up to now, Pakistan’s approach to counterterrorism has primarily depended on offensive actions and intelligence disruption. Initiatives such as Zarb-e-Azb and Radd-ul-Fasaad have disrupted militant networks and greatly diminished ISKP’s presence within the country. These tactical gains have not yet resulted in strategic stability, however, due to the ongoing presence of militant sanctuaries outside of Pakistan. Pakistan identifies both ISKP and Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan as terrorist groups that present fundamental threats. In contrast, the Afghan Taliban view ISKP as an adversary, yet do not regard TTP as a terrorist danger. The imbalance generates the gaps that are taken advantage of: fighters, facilitators, and commanders continuously shift between TTP and ISKP driven by pressure, lack of resources, and opportunism. While threat awareness and response lack coordination, militant networks do as well

Implications for Regional Stability and Policy Recommendations

The main threat to regional stability is the convergence and rivalry between the ISKP, the TTP, and the Afghan Taliban. Prospects for lasting peace are harmed by the ISKP’s international recruitment, leadership repetition, and doctrinal rigidity as well as the Taliban’s selective enforcement. For long-term peace, Pakistan and Afghanistan must reach a minimum counterterrorism agreement.

Pakistan considers both ISKP and TTP as terrorist threats, whereas Afghanistan regards only ISKP as a valid target. This difference continues to be the main barrier to collaboration. A unified framework for threat perception needs to be established, backed by collaborative border management, intelligence exchange, and enforcement systems overseen by the global community. Unless the selective counter-terrorism policy is rejected and all militant safe havens are eradicated, ISKP and its multiple branches will persist in turning terrorism into a means of security risk and political power across South and Central Asia.