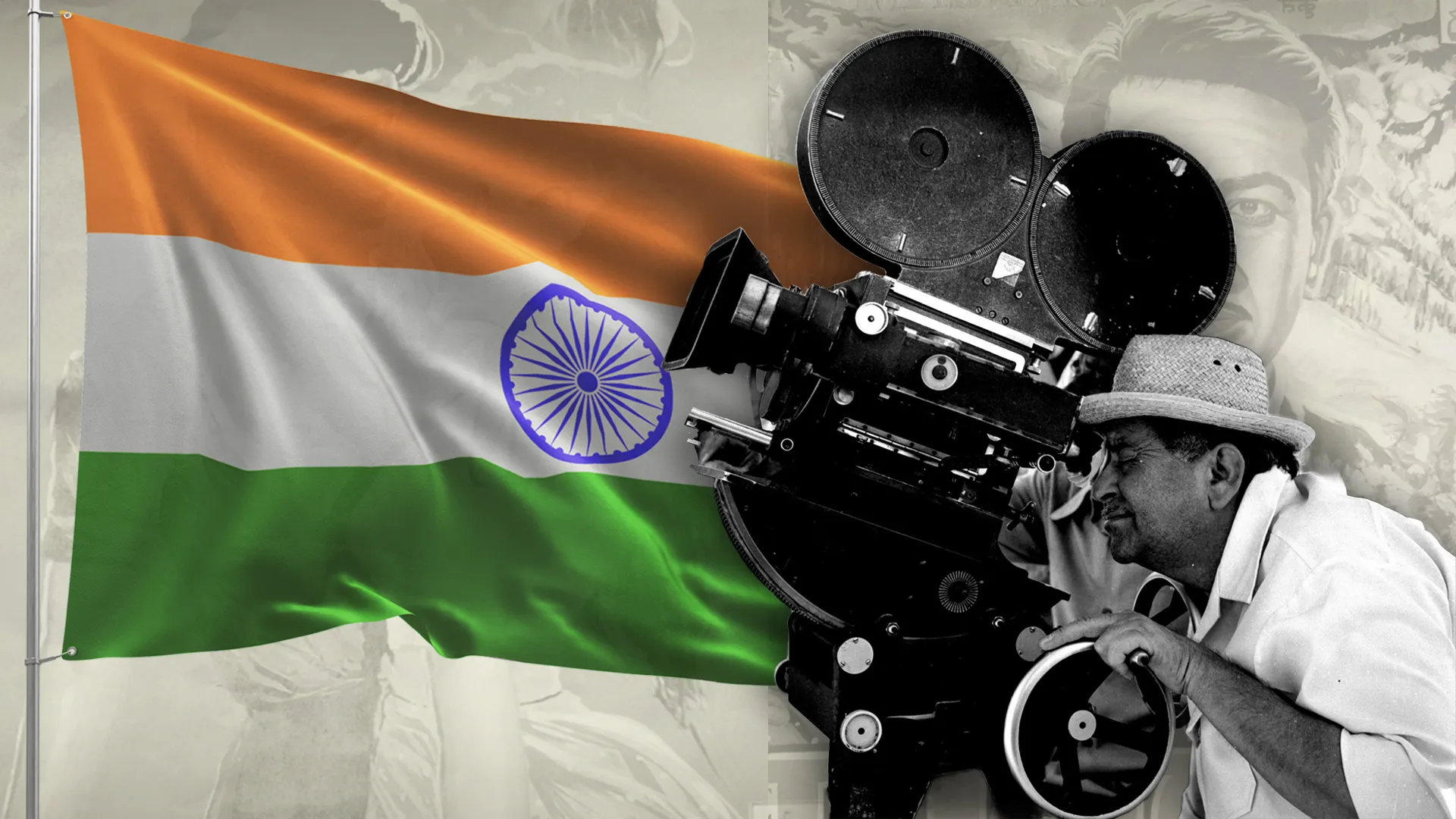

Political scientist Joseph Nye defined soft power as a nation’s ability to attract and co-opt rather than coerce. For decades, this concept served as the unwritten constitution of Indian cultural diplomacy. From the Soviet Union to the Middle East, Bollywood was the vanguard of this influence. It exported an image of India defined by romance, pluralism, and a certain mystic charm that endeared the nation to the world. It was a cinema that built bridges, often portraying Pakistan not as a nemesis but as a culturally estranged sibling in films like Veer-Zaara.

But today, that bridge is being burned, and the release of Aditya Dhar’s Dhurandhar (2025) illustrates just how stark the transformation has become. Set against the backdrop of Karachi’s Lyari gang wars, the film abandons the diplomatic subtlety of the past in favor of a raw assertion of power. However, the reported ban of the film across the Gulf states highlights the friction inherent in this approach. As cinema becomes a vehicle for hyper-nationalism, it risks severing the transnational bonds that historically sustained its global reach.

This transition is not merely an aesthetic choice. It reflects a structural repurposing of the industry. The post-2014 political landscape, coincident with the rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), has overseen a radical departure from the Nehruvian consensus. The secular idealism that once defined India’s soft power has been replaced by a muscular nationalism. In this new era, the goal is not attraction but assertion. The camera lens has shifted from the romantic valleys of Switzerland to the war rooms of New Delhi, and the script has moved from reconciliation to retribution. Dhurandhar is the crystallization of this new sharp power, where the industry functions less as an entertainer and more as a guardian of a specific geopolitical worldview.

Revisionism and the Internal Enemy

A critical component of this cinematic shift is the aggressive rewriting of history to suit contemporary political narratives. This revisionism operates on two fronts: the demonization of India’s Muslim past and the re-adjudication of modern conflicts to fit a binary of Hindu victimhood and Muslim treachery.

The most potent example of this is Vivek Agnihotri’s The Kashmir Files (2022). Ostensibly a film about the tragic exodus of Kashmiri Pandits in 1990, the movie was criticized by scholars and critics for flattening a complex geopolitical tragedy into a singular narrative of religious genocide.

While the suffering of Kashmiri Pandits is a historical reality, critics argue that the film engages in significant omission and distortion. It largely ignores the political context of the time, specifically the role of the then-Governor, Jagmohan. Historical accounts and critics have often pointed out that the exodus was facilitated, if not encouraged, by the administration to allow for a heavy-handed military crackdown, a nuance completely absent from the film. Furthermore, while the film portrays a holocaust-level massacre, official government data indicates that the number of Pandits killed during the onset of militancy was in the hundreds, rather than the thousands implied by the film’s imagery. By inflating these figures and erasing the administrative context, the film constructs a narrative that serves present-day electoral polarization rather than historical truth.

This revisionism extends deeper into history. Recent films have systematically attempted to erase the syncretic Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb that defined North India for centuries. Muslim rulers, from the Delhi Sultanate to the Mughals, are increasingly depicted as one-dimensional savages.

Movies like Padmaavat and Panipat portray Muslim kings as meat-eating, dark-clad barbarians, contrasting them with pristine, noble Hindu adversaries. This caricature ignores the reality that these dynasties were the torchbearers of Persian civilization in the subcontinent, commissioning the art, architecture, and revenue systems that define modern India.

The trend reached its peak with the release of The Taj Story (2025), starring Paresh Rawal. The film legitimizes the long-debunked Tejo Mahalaya conspiracy theory, which claims the Taj Mahal, a global icon of Indo-Islamic architecture, was originally a Hindu temple. By mainstreaming fringe pseudo-history, Bollywood is actively participating in a project to strip India’s history of its Islamic contributions, reframing the country as an exclusively Hindu civilizational state that was occupied rather than enriched by Mughal rule.

The External Enemy

In tandem with the internal othering, Bollywood has dramatically ramped up its anti-Pakistan rhetoric. While conflict movies like Border (1997) existed in the past, they were often balanced by the good neighbor films mentioned earlier. Today, the “anti-Pakistan” genre is a dominant financial vertical.

Films like Uri: The Surgical Strike, Fighter, Gadar 2, and now Dhurandhar function less as cinema and more as extensions of state foreign policy. They often follow a predictable template:

- Pakistan is not just a rival state but a breeding ground for irrational evil.

- The Indian state is infallible, hyper-competent, and justified in using extra-judicial violence.

This obsession serves a domestic purpose. It keeps the enemy at the gates fear alive, rallying the electorate around the flag. However, as noted with the ban of Dhurandhar in the Gulf, this strategy has diminishing returns abroad. The caricature of Pakistanis has become so extreme that it risks alienating global audiences who view such depictions as propaganda rather than entertainment.

The Limits of Cultural Hegemony

It is crucial to note that this hyper-nationalist, anti-Pakistan fervor is largely contained within the Hindi-language industry (Bollywood). A comparative analysis reveals a stark divergence in the cinemas of the South (Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam) and Punjab. While Southern cinema produces patriotic blockbusters, RRR being the prime example, their nationalism is often directed at colonial oppressors rather than neighboring states or religious minorities. Similarly, Punjabi cinema, despite the state’s direct scars from Partition, rarely indulges in the visceral anti-Pakistan hatred found in Hindi films, driven partly by shared linguistic heritage and market dynamics.

This geographic containment suggests that the Bollywood shift is not a reflection of a pan-Indian sentiment but is specifically tailored for the Hindi Belt, where the ruling party’s electoral machinery is most potent. As India seeks a permanent seat at the global high table, its cinema is increasingly abandoning its role as a cultural ambassador in favor of becoming a geopolitical bouncer. By replacing the soft power of plurality with the hard power of revisionism, Bollywood risks narrowing the definition of Indian identity. While movies like Dhurandhar may achieve box office dominance domestically, they project an image of an insecure nation to the world, one that builds its identity not on its inherent cultural richness, but on the systematic vilification of its neighbors and its own history.