The long-standing promise, formalized under the 2020 Doha Agreement, that Afghan soil would not be used to launch attacks against the international community, has dissolved into a dangerous reality, a nexus of regional and global jihadist groups now enjoys unprecedented freedom of movement and maneuver under an ideologically aligned regime. This dynamic not only threatens the immediate neighbors of Afghanistan but also ensures that the unelected regime in Kabul remains fundamentally unstable, perpetuating a cycle of chaos that ultimately victimizes the Afghan people.

The Setting: An Ideological Sanctuary

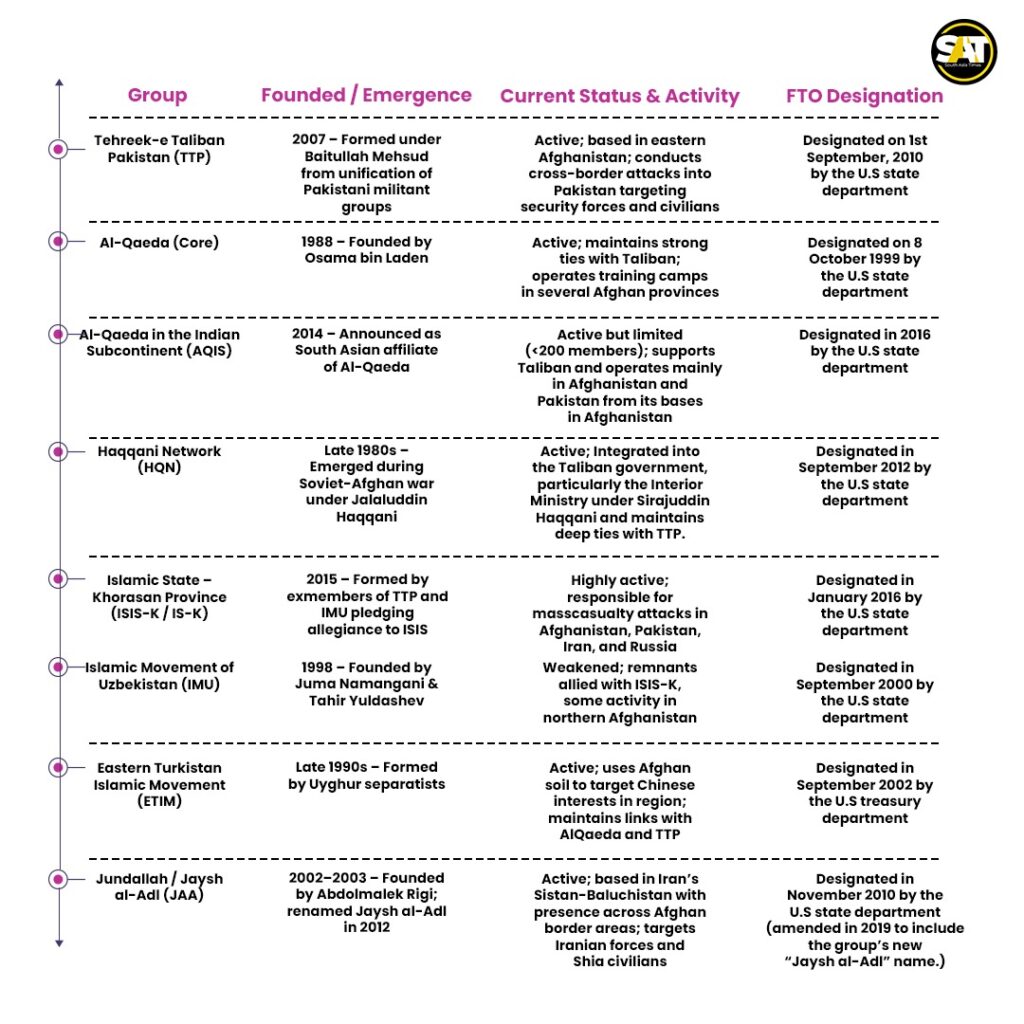

The current security landscape is defined by the symbiotic relationship between the de facto authorities, the Taliban and long-standing militant allies, most notably Al-Qaeda (AQ). United Nations reports have consistently noted that the link between the Taliban and Al-Qaeda remains strong and symbiotic, confirming that several terrorist groups now enjoy greater freedom to operate.. The presence of Al-Qaeda core leaders, including the deceased Ayman al-Zawahiri, in Kabul underscores the Taliban’s refusal to sever these ties, effectively validating Afghanistan as an ideological sanctuary.

While the Taliban has focused its resources on confronting its key internal rival, the highly active Islamic State, Khorasan Province (ISIS-K), this internal conflict does not mitigate the transnational threat. Instead, it creates a deeply fragmented and violent internal security environment, fertile ground for recruitment and fundraising. The situation has allowed various FTOs, all focused on specific regional targets, to consolidate their positions along Afghanistan’s permeable borders.

The Regional Threat Matrix

The presence of these groups is not merely symbolic; it represents a clear projection of external threat across three major geographical axes: Pakistan, Central Asia, and China.

Pakistan: The TTP Conundrum

The most immediate and critical threat is the surge in violence directed at Pakistan by the Tehreek-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP). Ideologically allied with the Afghan Taliban, whose victory it sees as its own, the TTP has been emboldened, with many of its leaders and fighters believed to have sought refuge and operational space in Afghanistan since 2021.

The cross-border instability has intensified dramatically, leading to a rise in well-organized, fatal attacks on Pakistani security forces. Despite trilateral talks mediated by regional players, diplomatic engagement between Kabul and Islamabad has virtually frozen due to the Afghan Taliban’s refusal to provide a credible, written commitment to dismantle TTP safe havens. The Afghan government’s reluctance to act against the TTP stems from the close political affiliations between the two groups. Any decisive move against its ideological ally would risk destroying the cohesion and internal unity of the Afghan Taliban itself, a price the regime currently seems unwilling to pay. This ideological conundrum effectively turns Afghanistan into a strategic launchpad for the TTP, straining Pakistan’s internal security apparatus.

China: The ETIM Factor

For Beijing, the key concern remains the East Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM), a group of Uyghur separatists designated by the UN Security Council as a terrorist organization. China’s primary goal in Afghanistan is preventing terrorism from spilling over into its western Xinjiang Autonomous Region, fearing ETIM will use Afghan soil to foment instability.

While ETIM’s real military strength is often debated, its presence in provinces bordering China, such as Badakhshan, represents an existential security headache for Beijing. China has demanded that the Taliban suppress the group, viewing a stable Afghanistan as crucial for its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) infrastructure projects across Central Asia. However, internal reports suggest that attempts to control ETIM fighters are pushing them towards the rival ISIS-K, further compounding the threat. This situation forces Beijing into transactional engagement with an unreliable Taliban, perpetually worried that their lack of control will turn ETIM into a more potent security risk.

Central Asia: The IMU and Tajik Taliban Threat

The Central Asian Republics (CARs), particularly Tajikistan, remain acutely vulnerable to transnational threats emanating from northern Afghanistan.

The IMU and Pan-Islamism: A primary concern is the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), which previously used Afghan territory for training and operations. Although weakened, remnants of IMU have aligned with ISIS-K, giving the group a pan-Islamist Salafist ideology aimed at replacing secular regimes in the CARs with a caliphate.

The Tehreek-e Taliban Tajikistan (TTT) / Jamaat Ansarullah (JA): A more recent and direct threat to Dushanbe is the formation of the so-called TTT, which is essentially a rebranding of the pre-existing Tajikistani militant group, Jamaat Ansarullah (JA). Operating from Afghanistan’s Badakhshan province, the TTT’s explicit goal is to overthrow the current secular Tajik government. Crucially, this group, led by figures like Mehdi Arsalan, is openly Taliban-affiliated, and its fighters have even been entrusted with securing key border districts with Tajikistan.

This arrangement is deeply provocative, turning a former threat into a quasi-official border force for the new Afghan regime. Tajikistan views this as a profound security risk, fearing TTT/JA will exploit local socio-economic troubles and potentially launch cross-border attacks. The presence of both the ISIS-K and the Taliban-backed, Tajik-nationalist TTT ensures that the entire Central Asian frontier remains a zone of intense geopolitical and military friction, compelling CARs to increase military cooperation with Russia.

The Human Cost of Perpetual Chaos

At the core of this escalating security crisis is the internal political structure of Afghanistan. The current Taliban rule is exclusionary, Pashtun-centered, and autocratic, prioritizing the authority of the supreme leader and resisting external pressure to moderate its policies.

The flourishing of terrorist groups on Afghan soil is not an accidental byproduct; it is intrinsically linked to the regime’s ideological foundations and its inability, or unwillingness, to create a stable, internationally legitimate state. These groups thrive in the absence of centralized, accountable governance, exploiting the lack of security and the pervasive economic collapse—a collapse which risks plunging 97 percent of the population into poverty.

As long as Afghanistan remains a safe haven, it will continue to suffer from perpetual conflict. The presence of FTOs, particularly the intense rivalry with ISIS-K, ensures that mass-casualty attacks remain a recurring feature of the security environment, disproportionately affecting civilians. This environment of constant instability, driven by an unelected and authoritarian regime that enables militancy, prevents reconstruction, halts economic recovery, and ensures that the common Afghan citizen, who has no say in the country’s direction, remains trapped in a cycle of insecurity, violence, and despair. Until the international community and regional powers address the root cause, a regime that derives legitimacy from the same ideological current that fuels these global terrorist groups, Afghanistan will remain a dangerous and deeply unstable hub for world terror.