The Taliban’s governance is not merely a political project, it is a theological one, rooted in a radical, monolithic interpretation of religion. At the core of their ideology lies a profound suspicion of any religious or ethnic group that deviates from their narrow definition of the faithful. To the Taliban, diversity is not a social asset but a form of fitna (social discord) or heresy. This exclusionary worldview has, for nearly three decades, made Afghanistan a graveyard for religious pluralism, as the group seeks to homogenize a historically diverse nation through a combination of legal disenfranchisement and physical elimination.

The First Emirate

When the Taliban first seized Kabul in 1996, their immediate priority was the purification of the Afghan state. This era was defined by a total lack of legal protection for religious minorities and the implementation of state-sponsored sectarian violence. The primary target during this period was the Hazara community, an ethnic minority that is predominantly Shia Muslim. The Taliban’s leadership, including figures like Mullah Niazi, openly labeled the Hazaras as infidels suggesting that their blood could be shed with religious justification. The most harrowing manifestation of this was the 1998 Mazar-i-Sharif massacre. Following the capture of the city, Taliban fighters engaged in a systematic house-to-house search, killing an estimated 2,000 to 5,000 civilians, mostly Hazaras.

This drive for religious homogeneity also extended to other Sunni denominations that challenged the Taliban’s Deobandi monopoly. In the 1990s, the Taliban initiated a hostile campaign against the Salafi community, particularly in their eastern strongholds. In Nangarhar province and the city of Jalalabad, where Salafism had a significant following due to historical links with cross-border movements, the Taliban acted with extreme prejudice. They viewed the Salafi rejection of traditionalist Hanafi jurisprudence as a direct threat to their religious authority. Reports from this period describe the Taliban forcibly seizing Salafi mosques in Jalalabad and arresting scholars who refused to pledge allegiance to the Taliban’s specific creed. This local repression in the east served as a blueprint for their national policy of silencing any Sunni voice that did not align with their rigid traditionalism.

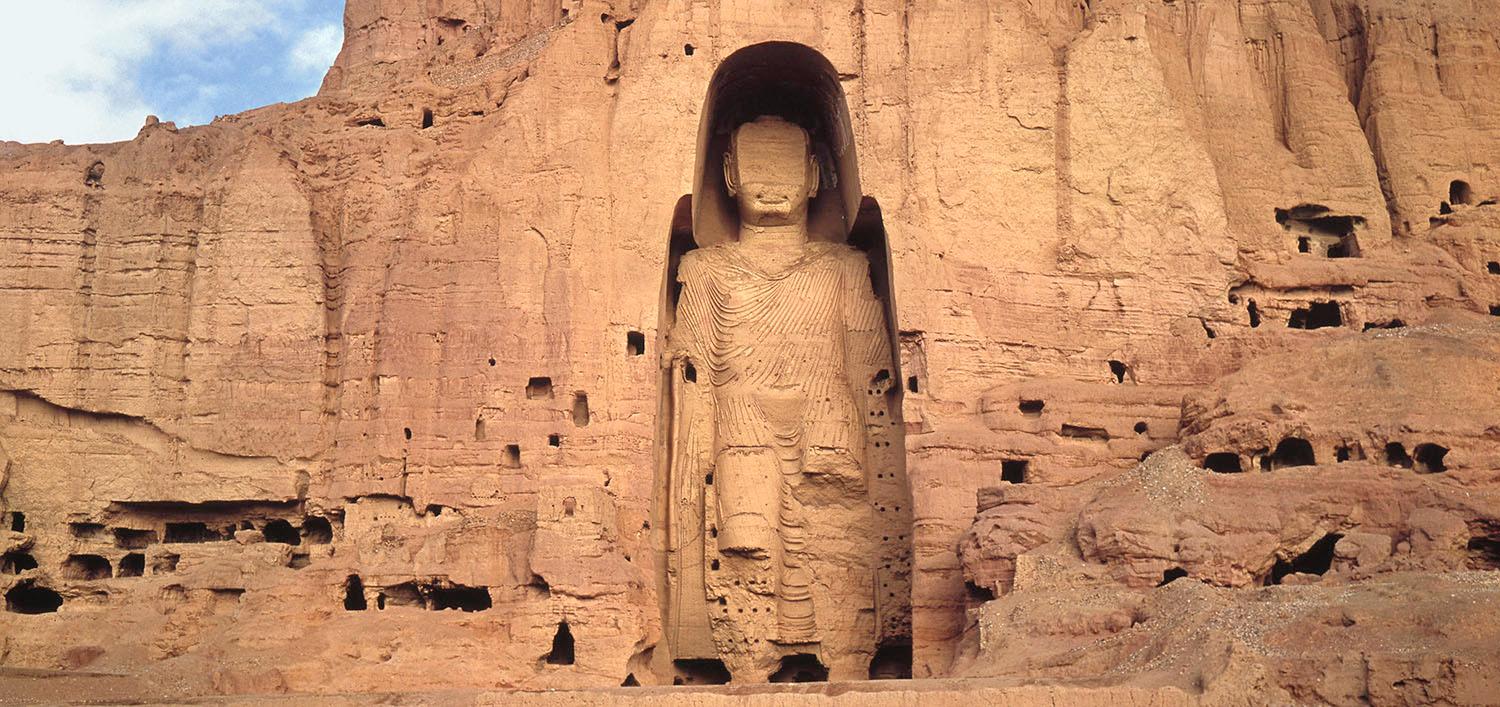

The demographic impact on non-Muslims was even more stark. In the 1970s, Afghanistan was home to approximately 700,000 Hindus and Sikhs. By the mid-1990s, this number had already plummeted due to the civil war, but under the first Taliban regime, the remaining population faced existential threats. In May 2001, the Taliban issued a decree requiring Hindus and Sikhs to wear yellow badges on their clothing to identify themselves as non-Muslims, a move that drew chilling comparisons to the Nuremberg Laws of Nazi Germany. This period also saw the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan in March 2001, a clear signal that pre-Islamic or non-Islamic heritage had no place in the new Emirate. By the end of this first rule, the Sikh and Hindu population had dwindled to fewer than 50,000 individuals.

The Insurgency Decades

During the twenty-year insurgency between 2001 and 2021, the Taliban’s tactics shifted. While they were not the sovereign power, they utilized targeted terrorism and shadow governance to maintain a climate of fear among religious minorities. This period was characterized by the sectarianization of the conflict, as the Taliban and their affiliates increasingly targeted soft sites such as places of worship and schools. Data from the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) shows a steady escalation in attacks targeting the Shia Hazara community during this time. For instance, in the first half of 2021 alone, UNAMA documented 20 attacks targeting Hazaras, resulting in at least 143 deaths and 357 injuries. The Taliban often denied direct responsibility for the most gruesome attacks, such as the May 2021 bombing of the Sayed ul-Shuhada school which killed over 85 people, mostly schoolgirls, yet their rhetoric and the environment of impunity they fostered enabled such violence.

The non-Muslim population continued its terminal decline throughout the insurgency. In 2018, a suicide bombing in Jalalabad killed 19 people, including Awtar Singh Khalsa, the only Sikh candidate for the Afghan parliament. By 2020, the Sikh and Hindu population had collapsed to roughly 700 people. The March 2020 attack on the Gurdwara Har Rai Sahib in Kabul, which killed 25 worshippers, served as the final catalyst for a mass exodus. By the time the Republic fell in August 2021, the number of Hindus and Sikhs remaining in the country was estimated at fewer than 250.

The Second Emirate

Since the return to power in August 2021, the Taliban have moved from insurgent violence to institutionalized persecution. Unlike the first era, which relied on localized massacres, the current regime utilizes a sophisticated legal framework to erase religious minorities from public life. The re-establishment of the Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice has been central to this. In August 2024, the Taliban enacted a Morality Law consisting of 35 articles that essentially criminalize any religious expression outside of their specific Sunni interpretation. Furthermore, the Taliban’s Minister, Khalid Hanafi, has been recorded using dehumanizing language, describing Hindus and Sikhs as worse than animals for their non-Islamic beliefs.

Today, the Taliban are using the presence of the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) as a convenient pretext for a renewed crackdown on Salafis. While ISKP does draw recruits from Salafi circles, the Taliban have adopted an approach of collective punishment. Reports indicate that at least 100 Salafi clerics have been killed and dozens of their mosques closed since the takeover. High-profile figures like Sheikh Abu Obaidullah Mutawakil were abducted and later found dead, despite having no proven ties to ISKP. This anti-Kharijite campaign allows the Taliban to eliminate theological rivals under the guise of counter-terrorism, effectively criminalizing the entire Salafi identity.

The current data reflects a community on the verge of total extinction. As of late 2024, fewer than 50 Sikhs and Hindus remain in Afghanistan. For the Hazaras, persecution has moved toward land dispossession. In provinces like Daikundi and Helmand, thousands of Hazara families have been forcibly evicted from their ancestral lands. Meanwhile, the small, underground Christian community has been driven into total secrecy, facing the threat of execution for apostasy. In conclusion, the Taliban’s approach has evolved from the crude brutality of the 1990s to a calculated, state-managed erasure. Afghanistan, once a crossroads of civilizations and faiths, is now being forcibly transformed into a monolith where dissent is heresy and diversity is a crime.

![US Embassy in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, amid heightened regional tensions following the Iran crisis. [Image via AFP].](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/image-3-3-scaled-1.webp)