As Amartya Sen reminds us, “development is not just growth; it is the freedom to live a life one values”.

In India, this principle is tested as the nation balances its development goals with the growing pressures of climate change. India’s commitment to net-zero emissions by 2070 rests at the intersection of two uncomfortable truths: per-capita equity and climate urgency. On the one hand, India’s per-capita emissions are only about one-third of the global average; on the other hand, it is one of the most climate-vulnerable countries in the world, with cities and farms already experiencing floods, heat and water stress.With COP30 and India’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) updating process in 2025, the more immediate question is not about moral defensibility of a distant target, but whether or not that target will be translated into credible short-term action.

Why does India’s case for a later horizon look fair?

Equity is important. The relatively low per-capita emissions in India offers the political and ethical rationale for a development-sensitive timetable rather than a more sudden, universal decarbonisation schedule. By following a rapid and universal emissions reduction schedule like high income economies, India risks undermining the poverty reduction and industrialisation priorities that underpin its public policy objectives.

This argument of equity is not just theoretical. Adaptation spending grew from 3.7% to 5.6% of GDP between FY16 and FY22, signifying a serious fiscal commitment to protect people and their assets. Behaviour change initiatives, such as Mission LiFE, aim to align consumption patterns with circular economy goals while nudging households towards a lower-emissions lifestyle.The coastal ecosystem restoration initiative, created under MISHTI in 2023, which aims to restore 540 sq. km of mangroves by 2028 while creating livelihoods and carbon sinks, can be viewed as a concrete example of policy that links adaptation, livelihoods and mitigation.

The energy landscape is clearly showing momentum for the transition. By November 2024, non-fossil installed capacity had reached 46.8% (213,701 MW), showing that India is making progress toward its 2030 non-fossil capacity target of 50% (IEA). The large-scale programmes—including rooftop solar programmes, approved solar parks, KUSUM solarised pumps, viability funding for offshore wind, proactive awards for green-hydrogen technology, and domestic PV manufacturing through the PLI—suggest coordinated steps were taken toward developing both capacity for deployment and an industrial supply chain toward a low-carbon future. Sovereign green bonds, green debt instruments, and RBI instruments for incentivising green deposits are beginning to mobilise domestic financial resources to fund that transition (material permitting).

Cumulatively, these indicators bolster the case for a pathway to 2070 that is fair rather than motley, sequenced, and within the interests of development in its broader meanings.

Why can 2070 become a dangerous delay?

Equity doesn’t eliminate vulnerability. India still ranks seventh in climate vulnerability globally and is experiencing rising heat waves, risk of floods, biodiversity loss, and severe water stress. Agriculture is inherently climate sensitive and critical to food security and livelihoods for millions of people. Postponing mitigation of price and production shocks increases vulnerability to transient risk.

Urban areas illustrate the urgent challenge. Productivity diminishes and livelihoods are threatened from heat stress, repeated flooding, and diminished water supply and access; while key adaptation programmes are underway—AMRUT and Smart Cities Mission are commonly cited examples—most of which are very scale-specific. Only 64 urban local bodies achieved the highest Water+ mark, suggesting the quality of urban transformation is inadequate (provided materials). Adaptation measures are critical but they fail to substitute a pathway to increased frequency, with rising global emissions.

The finance gap exacerbates the risk. Recent multilateral outcomes estimate a collective finance goal of USD 300 billion annually, amount insufficient relative to the total USD 5 – 6 trillion needed to support India’s aspirations for rapid, resilient transition (COP29 outcome and India’s internal estimates). Plans considering the 2070 horizon, while official international climate finance and technology transfers remain undeveloped, mean India faces increasing costs of adaptation and delayed mitigation.

The concept of technical realism is important as well. Routes to 2070 will have an earlier peaking window—roughly 2040–45. If there is no stated peaking year and intermediate binding targets, 2070 could be an endpoint without any guardrails: politically useful but practically fragile (CSTEP/CEEW analysis).

A practical public-policy middle path

India’s 2070 net zero pledge cannot be evaluated in the abstract; its credibility will depend on events over the next two decades. Three anchors of policy action will be needed to avoid allowing the pledge to drift into an empty commitment:

1. Announce a clear peaking window for emissions, and interim milestones:

In the absence of an announced peak for emissions, the goal of 2070 would become a moving goalpost. India should announce a peaking window of 2040-45, along with mandatory interim milestones for 2030 and 2040 (CSTEP; CEEW). This would convert the completion date of 2070, from an ambition and target to a clear process and sequence that builds both internal and international credibility.

2. Fund the transition using existing financing flows:

Funding will determine whether climate policy in India is reality or rhetoric. Finding ways to reroute part of the National Infrastructure Pipeline ( ₹ 111 lakh crore), and the National Monetisation Pipeline, to bankable green projects, will create momentum. Once some momentum is created, sovereign green bonds and restructured PPP models can begin to crowd in private financing. The International Energy Agency estimates India will require roughly US$145 billion/year, until 2030, to stay on track (IEA 2023). Mobilising finance now, and not waiting for international transfers to take place, will begin the long road to building resilience against the projected total funding requirement of US$5-6 trillion by mid-century.

3. Prioritizing high return decarbonisation and state action:

Some sectors can provide outsized benefits if they are rapidly scaled up. One leading example is Indian Railways, which seeks to reach net-zero operations by 2030 with 30 GW of renewable energy. Other “early wins” include rooftop and corridor-scale solar, grid upgrades through the Green Energy Corridors, and storage facilities, because there are ways to mitigate and have associated economic co-benefits. However, national targets also need to be localised. Integrated modelling at the state level with sectoral pathways, and reskilling programmes for workers in coal and carbon-heavy industries, will help achieve transitions that are both technically feasible and socially just (CSTEP; CEEW).

Conclusion

Net Zero 2070 is either a fair trade-off, or a reckless deferment. What matters is not the year, but the actions India engages in between now and 2030. Specifically, the establishment of clear peaking targets, credible interim targets and decisive state-level action to plan and prepare will determine whether the commitment is seen as confidence-building or a gesture of ambivalence. India is not lacking ambition, it is lacking time. In order to move from equality to credibility, public policy must now focus on measurable outcomes that deliver today rather than placing belief in an aspiration that is far off. Yielding success means that 2070 is not procrastination, but validation that development and climate action can work hand-in-hand.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own. They do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of the South Asia Times.

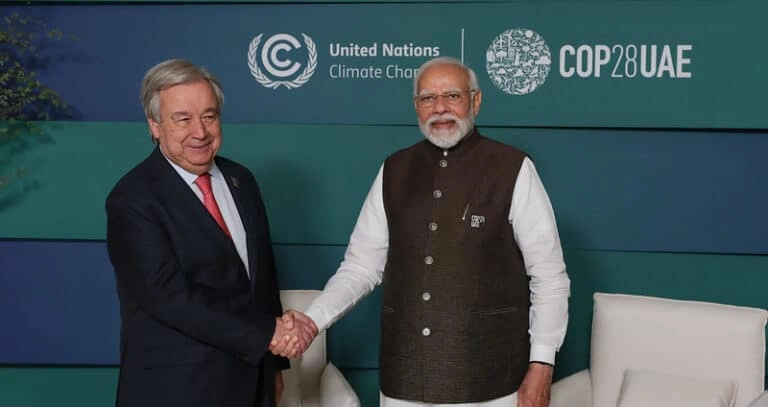

![Prime Minister Narendra Modi with External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar at an official event. [Photo Courtesy: Praveen Jain via The Print].](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/20-scaled-e1755601883425-1024x576-1.webp)