Based on the thread initiated by Dr. Hassaan Bokhari (@shbokhari13), we are presenting the subject matter in its more expansive format. Enjoy reading!

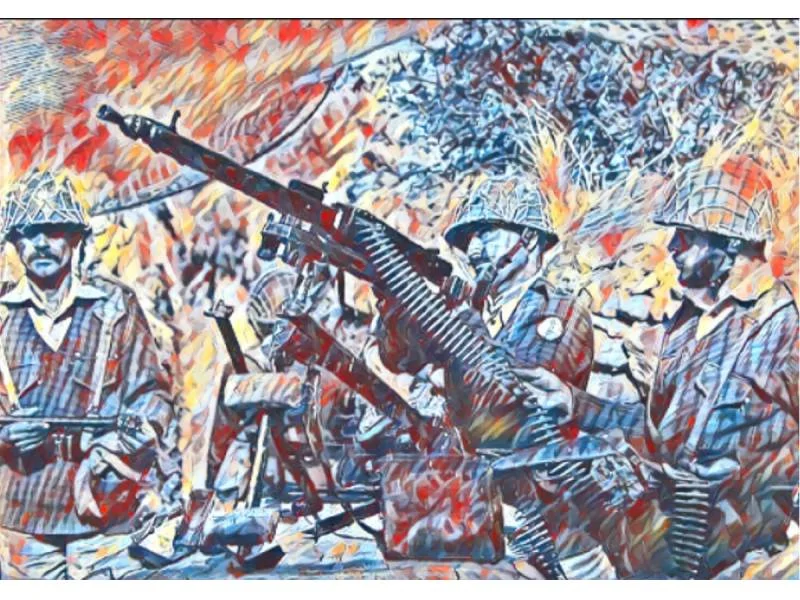

1965 was a watershed year for Pakistan. In it, a highly charged election was contested, in which Ayub Khan won office but lost his reputation and legitimacy in most of the country’s eyes. Then the war of 1965 tested the established military doctrines, which we found wanting.

Ayub Khan’s rule began in 1958 and brought order to a chaotic Pakistan. The economy and industrialization took off. A robust foreign policy was pursued, and overall, the people seemed happy with the government in the first few years. But probably the biggest pitfall of a dictatorship is that it is too dependent on a single person. A dictatorship that doesn’t give birth to a rules-based order is doomed to fail. And when it fails, all the good it has done gets washed away with it, leaving only ruins.

Ayub Khan also tried to give an ideological and constitutional basis to his dictatorship. He postulated a primary nationalist/secular ideology for Pakistan with a sprinkle of an “Islamic touch.” The result was a confused ideology that was neither Islamic nor nationalist. Anyhow, the Bengalis could and did argue that if nationalism was to be the nation’s ideology, then Bengali nationalism made more sense to them. The European brand of nationalism that Ayub admired could not work in an ethnically and linguistically diverse country such as Pakistan. He even tried to remove the word Islamic from the name “Islamic Republic of Pakistan.”

Ayub’s attempts at constitution-building resulted in the 1962 constitution, which gave all powers to a president who was to be elected by an electoral college of 80,000 Basic Democracy (BD) members. This indirect mode of election tried to make the old politicians (who did large constituency politics) irrelevant. Had Ayub himself followed his own constitution, it might have succeeded in granting him legitimacy. But the 1962 constitution was frequently and substantially amended in a couple of years, and most of these amendments were clearly made to serve the interests of the ruler and prolong his rule.

In 1964, Ayub Khan was still reasonably popular, and his economic policies appeared to be successful in developing Pakistan. His government was the first in Pakistan to have invested heavily in East Pakistan as well, and industrialization was moving forward at a fast pace over there. The opposition to Ayub consisted of old conservative politicians like Khawaja Nazimuddin, Nurul Amin, and Chaudhry Mohammad Ali, Islamists like Maulana Maududi, Leftists like Maulana Bhashani, and Sub-Nationalists like Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Wali Khan. All of them had virtually nothing in common apart from a desire to depose Ayub Khan. They formed an alliance named the Combined Opposition Parties (COP) to contest the presidential election against Ayub Khan, which was scheduled for January 1965. The biggest challenge for the COP was to nominate a joint candidate acceptable to all of them. Former PM Chaudhry Mohammad Ali was unacceptable to sub-nationalists like Mujib. A very promising candidate, General (R) Azam Khan, was named, and all seemed to agree at first. General Azam had served as Governor of East Pakistan in the early years of Ayub’s government, and he had earned immense popularity there through his honesty, modesty, and hard work. Azam was also a retired general who had a good reputation both in the army and in West Pakistan. Apparently, the prospect of his candidacy caused much worry in government circles. Ayub Khan’s wonder kid, Z. A. Bhutto was charged with solving this problem. Allegedly, Bhutto bribed a certain Mr. Masih-ur-Rehman, who was a confidant of Maulana Bhashani. Masih-ur-Rehman convinced Maulana Bhashani to veto Azam Khan’s candidacy on the basis that he had been a key official under martial law and hence wasn’t a “democratic” choice. Finally, the COP settled on the name of Quaid-e-Azam’s sister, Miss Fatima Jinnah, who hadn’t taken part in active politics for a very long time. Fatima Jinnah, despite her advanced age, ran a very spirited campaign. The COP leaders also forgot their differences temporarily to rally behind her. Fatima Jinnah pulled huge crowds all over Pakistan, especially in East Pakistan. East Pakistan had always been comparatively less enthusiastic about military rule because its share in the military was much less than West Pakistan.

The election campaign was marred by opposition allegations of government heavy-handedness and pre-poll rigging. The election results came out in favor of Ayub Khan, who received 63% of the votes of the BD members. Miss Fatima Jinnah received 46% of the votes in East Pakistan and emerged victorious from both Karachi and Dhaka. It was generally believed then that Ayub Khan manipulated the elections in his favor. The BD members from rural areas were specially given inducements and bribes to vote for Ayub. Almost all historians are unanimous that, had the election been conducted on a universal adult franchise, Miss Fatima Jinnah would have won.

Ayub Khan had taken control of the country with a vow to root out dishonest politicians. Now, most of the country thought he had become one himself. His son, Gohar Ayub, led a victory procession in Karachi soon after the election, which degenerated into violence against opposition supporters and innocent passersby. By this time, allegations of financial corruption by Ayub’s family, especially his sons, were also surfacing. All this managed to undermine Ayub’s image a lot. But Ayub was still in a very strong position. The economy was doing well, the army was happy, and since Fatima Jinnah didn’t seem much interested in active opposition after losing the election, the alliance of opposition parties seemed to be over.

The 1965 war delivered another jolt to the government of Ayub Khan and Pakistan. I will confine the discussion here to the effects of the 1965 war on East Pakistan. The war ended in a stalemate, but it generated a lot of negatives regarding East Pakistan. Less than 10% of Pakistan’s military assets were deployed for the defense of East Pakistan during the 1965 war. The military doctrine (created by Ayub Khan in the 1950s) was that East Pakistan’s defense would be conducted from West Pakistan. It meant that all major assets and strike forces would be kept in West Pakistan. If India dared to attack East Pakistan in force, powerful forces from West Pakistan would launch offensives against India in Kashmir and Punjab. The 1965 war proved that this strategy didn’t work. During the war, both of Pakistan’s offensives against India (at Akhnur and Khem Karan) failed despite facing almost equal odds during the offensives. Indian offensives against West Pakistan also failed miserably, despite India commanding 3:1 numerical superiority in both cases (at Lahore and Sialkot). But shrewd strategists like Gen. Akhtar Hussain could clearly see that India could post forces in a 1.5:1 ratio against West Pakistan in a future war. India could deploy these forces in a defensive role and simultaneously gain a 1:7 or 8 numerical superiority against East Pakistan, which could expect no help from West Pakistan. On this basis, Gen. Akhtar had predicted in 1967 that India would try her luck against East Pakistan in the next war.

During the 1965 war, East Pakistan’s communications with West Pakistan had been severed, and the whole province felt that it had been left at the mercy of the Indians. The situation was such that it prompted secessionists like Sheikh Mujib to feel secure enough to show their true colors. During the war, he reportedly told the Governor of East Pakistan, Abdul Monem Khan, that the Indians had West Pakistan by the throat and it was a golden opportunity to declare the separation of East Pakistan from West Pakistan!

Ayub Khan’s star foreign minister, Z. A. Bhutto (who was the main architect of the 1965 war), tried to claim credit for East Pakistan’s defense during the 1965 war. He declared that India didn’t attack East Pakistan because China had warned India sternly against such an escalation. According to Mr. Bhutto, this Chinese ultimatum (a product of his successful foreign policy) had “saved” East Pakistan. Bhutto’s statement angered the Chinese, who expressed chagrin at the suggestion that East Pakistan’s defense was their responsibility! But Bhutto’s statement was picked up eagerly by the Bengali sub-nationalists like Sheikh Mujib, who said that if West Pakistan, despite dominating Pakistan’s military (paid for equally by both wings), couldn’t defend East Pakistan and China was required to do that job, then why did East Pakistan need West Pakistan? After all, it could become an independent country and do its own deals with China or with India for that matter. Ayub himself had weakened the resonance of Islamic ideology as a unifying factor between both wings. It was hard for any Bengali bereft of Islamic solidarity to understand why East Bengal should face mortal peril due to West Pakistan’s “obsession” with liberating Kashmir. Before the 1965 war, pro-Pakistan elements frequently advocated unity on the basis of Islamic solidarity and the assertion that West Pakistani military muscle was essential for East Pakistan’s security. Ayub’s policies and the 1965 war had taken both arguments away from pro-Pakistan elements.

Some months after the 1965 war, Sheikh Mujib unveiled his famous six points. There wasn’t much new in them. They called for complete provincial autonomy, with only defense and foreign affairs resting with the center. These same demands had been made by the Awami League, Maulana Bhashani, and many others in East Pakistan since 1949. But the difference this time was the man making these demands and the interpretation of these demands given by him and his lieutenants like Tajuddin. Sheikh Mujib’s interpretation of the six points frequently bordered on secession and sometimes even crossed that barrier. For the first time, the word “liberation” (Mukti) was now frequently used in the context of “Punjabi Tyranny.” A narrative based on racism against non-Bengalis was being advocated by Mujib and co., who labeled all non-Bengalis as “Punjabis” regardless of their ethnicity.

The struggle for Union vs Secession in East Pakistan had entered the acute phase in the aftermath of the 1965 war with the launching of the six-point movement by Sheikh Mujib. Great foresight, sincerity, patience, and wisdom were needed now to preserve the unity of Pakistan. Sadly, such qualities were almost non-existent in the echelons of power.

Read more

| Rise of Mujib and The Agartala Conspiracy |