The contours of global power are undergoing a profound transformation. In what scholars increasingly describe as a “New Cold War,” control over critical technological inputs rather than fossil fuels defines national security and economic leverage. At the center of this struggle are Rare Earth Elements (REEs), a group of 17 metals whose unique properties make them indispensable for advanced military capabilities and central to the global transition toward a net-zero emissions economy. As David S. Abraham observes,

“Whoever controls the elements controls the future,”

a statement that captures the strategic influence embedded in these resources. Although rare earths are not geologically scarce, their processing and refining capacity is concentrated in ways that create severe vulnerabilities for Western powers. China currently dominates nearly every stage of the REE value chain, controlling around 90 percent of global processing and refining. This grip allows Beijing to impose targeted export restrictions and manipulate global supply flows. The 2010 embargo against Japan demonstrated how effectively China can weaponize its position. Today, Western states, including the United States, European Union members, Australia, and Japan have shifted away from reliance on free-market approaches, opting instead for state-backed strategies, long-term contracts, and multinational partnerships to secure alternative supply chains.

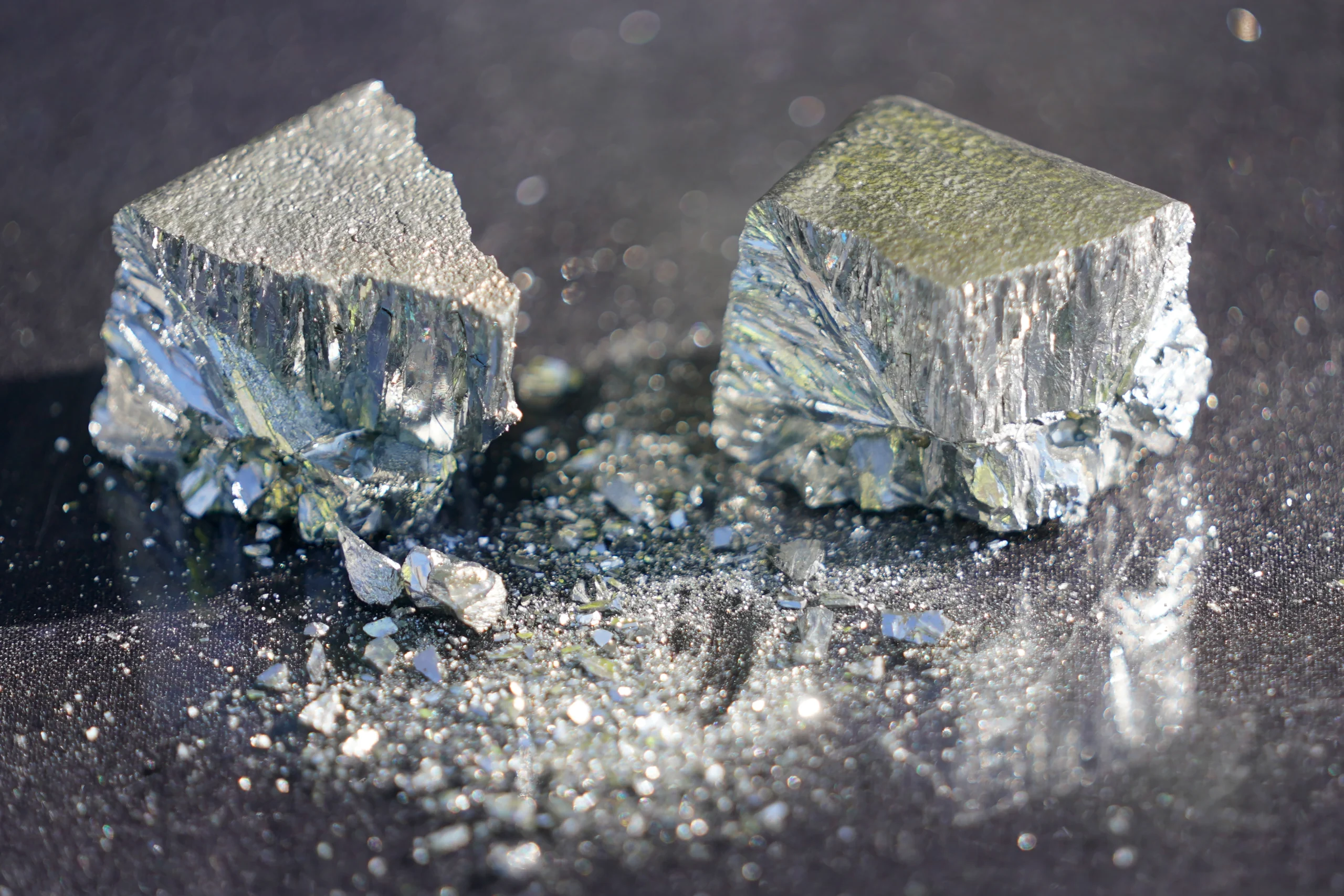

The Foundational Role of Rare Earth Elements

Rare Earth Elements are abundant in the earth’s crust but extremely difficult to extract and refine due to chemical similarities and environmental hazards. Their exceptional magnetic, catalytic, and conductive properties make them irreplaceable for high-performance technologies. Guillaume Pitron warns,

“We are entering a new war the war for rare metals and its battlefield is the entire planet,”

emphasizing the geopolitical stakes surrounding these resources. Rare earths enable the modern military ecosystem, underpinning night-vision goggles, precision-guided munitions, radar systems, stealth capabilities, and satellite components. Heavy REEs such as Dysprosium and Terbium are crucial for producing high-temperature permanent magnets used in fighter jet engines, missile guidance systems, and advanced computing. Minerals like Gallium and Germanium are essential for semiconductors that power high-frequency sensors and emerging laser-based weaponry. As Chris Miller notes,

“The semiconductor is the new terrain of geopolitical competition,”

tying mineral dependency directly to technological dominance. Rare earths also sit at the heart of global decarbonization. Electric vehicles rely on Neodymium magnets reinforced with Dysprosium for high-temperature resistance, while modern wind turbines use REE-based magnets to maximize efficiency. This creates a strategic paradox: the West’s push for clean energy increases its dependence on China, whose processing dominance strengthens both its economic position and its military-industrial capabilities.

Anatomy of a Global Chokepoint: China’s Vertical Integration

China’s dominance spans every stage of the rare earth value chain mining, refining, separation, processing, and magnet production creating an unprecedented strategic chokepoint. The United States, for example, imported 80 percent of its total REE consumption in 2024, underscoring the depth of dependency.

China’s control over the rare earth value chain is deep and strategically decisive. It begins at the mining stage, where China produces around 60 to 71 percent of the world’s rare earth ores, giving it significant leverage even though some diversification is possible through countries like Australia and the United States. This dominance becomes far more critical in the refining and separation phase, where China holds roughly 87 to 91 percent of global capacity, allowing it to dictate purity standards and maintain the most important chokepoint in the entire chain. The monopoly intensifies in the processing of heavy rare earth elements used in high-temperature magnets for defense systems and electric vehicles where China controls an extraordinary 98 to 99 percent of global capacity, leaving the rest of the world almost entirely dependent.

Finally, China produces nearly 90 percent of the world’s permanent magnets, giving it decisive influence over the finished components essential for advanced military technology, renewable energy infrastructure, and consumer electronics. Together, these stages form a vertically integrated system that grants China unparalleled geopolitical leverage and exposes the vulnerabilities of Western industrial and security strategies.

Western economies face long-term cost disadvantages: processing rare earths outside China is 25 to 35 percent more expensive due to environmental regulations, labor costs, and multiyear permitting delays. Waste treatment costs can reach 2,000 dollars per tonne in the West compared to as low as 50 dollars in China. Even when mines exist such as Mountain Pass in the United States they have historically relied on Chinese refining capacity, highlighting how long and costly it is to rebuild technological ecosystems that China spent three decades perfecting.

Geopolitical Weaponization: A History of Resource Coercion

China’s dominance over rare earths is a geopolitical asset, not simply an economic advantage. The 2010 embargo on Japan revealed the use of supply disruption as diplomatic pressure. In 2025, Beijing expanded its strategy by imposing export and technology restrictions on REEs, Gallium, Germanium, and Graphite, directly slowing Western efforts to diversify. These tactics echo historical oil politics but with far deeper leverage because rare earth processing is more specialized, more capital-intensive, and more vertically integrated. As Heller and Salzman emphasize,

“Control of resources, not their abundance, is what determines geopolitical power.”

The Allied Response: Strategic Autonomy and Resilience

The United States is rapidly reindustrializing critical mineral supply chains. Through the Department of Energy’s Advanced Materials and Manufacturing Technologies Office and Pentagon-backed initiatives, Washington is financing domestic mines, magnet plants, recycling systems, and material substitutes. Support for Mountain Pass, guaranteed procurement contracts, and strategic stockpiles are designed to reduce

The EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act aims for 40 percent of strategic material processing to occur within Europe by 2030, with at least 10 percent mined domestically. Yet environmental opposition, bureaucratic delays, and limited funding continue to slow progress. While the EU has introduced supply chain stress tests, the lack of industrial-scale capacity leaves Europe vulnerable to sudden disruptions.

Australia, particularly through Lynas Rare Earths, plays a central role in global diversification. The 8.5 billion dollar U.S.–Australia partnership supports new processing capacity, magnet plants, and cooperative research. Coordination with Japan, South Korea, and other Indo-Pacific democracies strengthens redundancy, ensuring that no single chokepoint can destabilize allied economies or military systems.

Strategic Imperatives and Conclusion

The rare earth competition reveals a paradox: the technologies needed for a cleaner future and stronger defense architecture depend on supply chains dominated by a strategic competitor. To avoid long-term vulnerability, Western states must accelerate permitting processes, fund large-scale processing facilities, expand recycling, invest in substitute materials, and build robust strategic reserves.

As David S. Abraham, Guillaume Pitron, Chris Miller, and Deng Xiaoping collectively illustrate, rare earths represent both the currency and battlefield of twenty-first century power. States that fail to secure stable supply chains risk ceding technological, economic, and military advantage to a single dominant actor reshaping global order for decades to come.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are the author’s own. They do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of the South Asia Times.