The return of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA) in 2021 was defined by speed, military effectiveness, and, crucially, the immediate implementation of a hyper-centralized political order. By 2025, the IEA, under the tightly controlled direction of Supreme Leader Hibatullah Akhundzada from Kandahar, has proven adept at military and financial consolidation, effectively controlling the country’s territory and revenue streams. Yet, this stability is illusory, built upon a political structure that is fundamentally fragile. The current regime represents an extreme, ethnically exclusive iteration of the centralized state model that has historically guaranteed violent instability in Afghanistan.

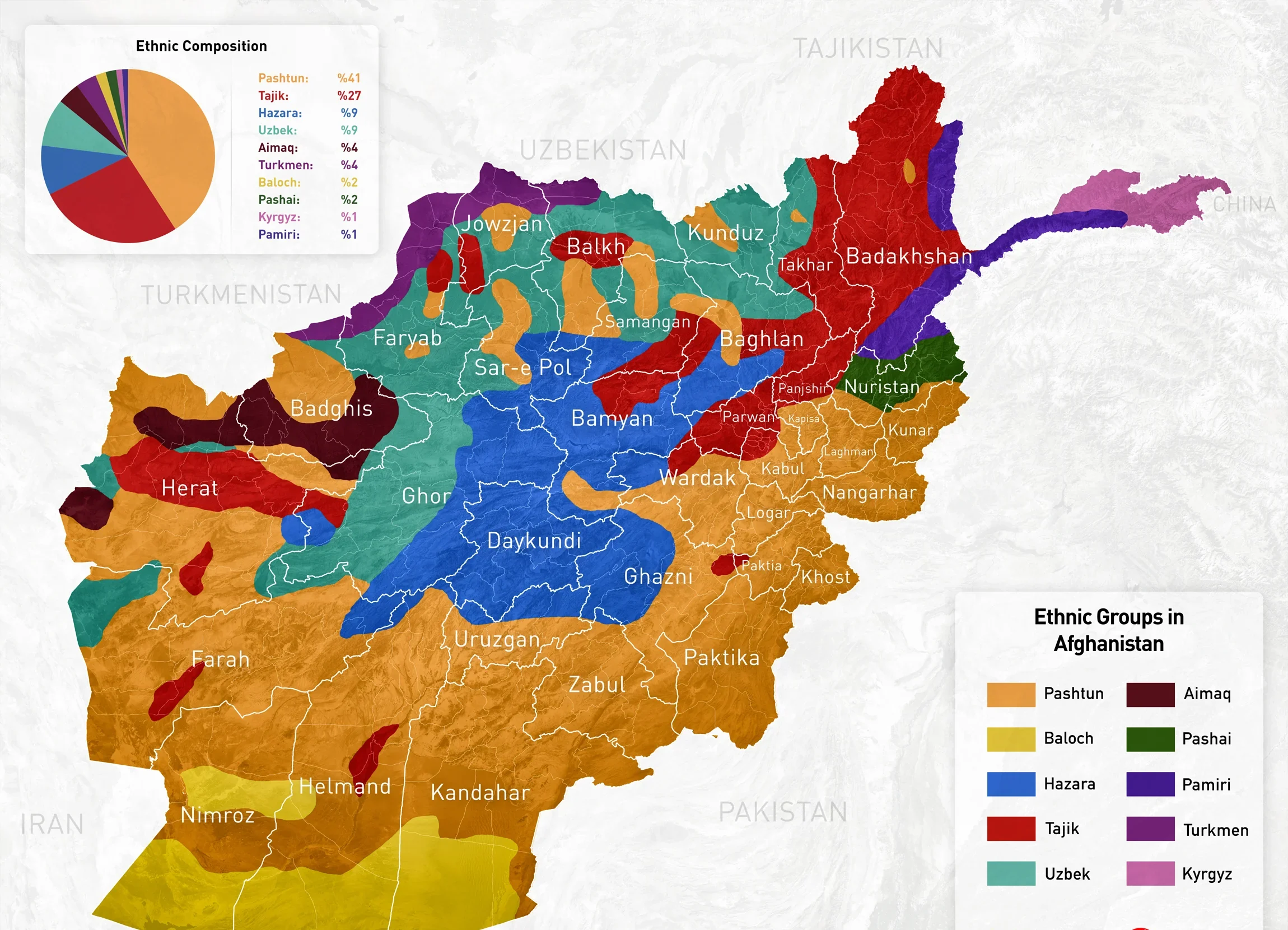

This strategy of centralizing power overwhelmingly in the hands of the Pashtun ethnic group, particularly the southern Pashtun factions, is not a path to enduring governance but a return to the structural flaws that toppled every previous strongman regime. Historical analysis shows that ethnic conflict in Afghanistan centers not on secession, but on who will dominate the state and subordinate others. By eliminating all non-Pashtun and non-Taliban factions from meaningful power, the IEA has set the stage for a long-term political failure rooted in historical and demographic reality.

The Iron Amir’s Ghost: Centralization

The foundation of modern Afghanistan’s instability lies in the late nineteenth-century reforms of Amir Abdur Rahman Khan, the Iron Amir. Rahman ended regional political autonomy and concentrated all power in Kabul, establishing Pashtuns as the politically privileged group. This model, while guaranteeing a brief period of dynastic control, proved inherently volatile. It is a recurring pattern that every Afghan ruler who relies on such extreme centralization eventually faces violent instability or exile. This demonstrates that extreme centralization fundamentally contradicts Afghanistan’s regional diversity.

This volatility was graphically illustrated in the 1929 Afghan Civil War. When Habibullah Kalakani, an ethnic Tajik, briefly interrupted the Pashtun monarchy to seize power in Kabul, his non-Pashtun government was swiftly perceived by the Pashtun majority as a usurpation of the established ethnic hierarchy. This perceived threat to Pashtun dominance caused Pashtun tribes to rally for the cause of ethnic solidarity, leading to Kalakani’s violent overthrow and execution by Pashtun leaders who restored the traditional power structure. History shows that non-Pashtun control is intolerable to the Pashtun political core, but equally, a hyper-centralized Pashtun state is intolerable to all other ethnic groups.

In 2025, the Taliban’s Islamic Emirate has replicated, and arguably intensified, this centralized structure. The IEA leadership is exclusively Pashtun, dominated by senior figures from the southern and eastern regions, including Supreme Leader Hibatullah Akhundzada, Prime Minister Mullah Mohammad Hasan Akhund, and deputies like Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar and Interior Minister Sirajuddin Haqqani. The IEA leadership, overwhelmingly Pashtun, with minimal non-Pashtun representation in senior ministerial and gubernatorial posts, has effectively purged non-Pashtun Taliban commanders and refused to integrate any former warlords or politicians from the defeated Republic. The creation of parallel institutions and the enforcement of policies from the tightly-knit Kandahar office privileged a specific, narrow ethnic and regional faction: the southern Pashtun Talibs.

This exclusive control violates the tradition of the multiethnic state as the accepted norm, shifting the historical conflict from a debate over dominance within a shared framework to an outright, exclusionary ethnic hierarchy. Unlike the previous Pashtun dynasties, which relied on local Pashtun and non-Pashtun elites as junior partners in government, the IEA’s ideological rigidity precludes such pragmatic co-option. It has supplanted the failed, corrupt centralization of the Karzai and Ghani governments with an absolute centralization that is even less accommodating of regional difference, fueling the resentment that inevitably leads to instability.

The Misplaced Loyalty of a Pre-Nationalist Society

A critical misjudgment of the IEA’s centralized model is its failure to account for the primary source of Afghan political cohesion: location, not nationality. For most Afghans, primary loyalty is local, to kin, village, valley, or region, with cross-cutting ties of intermarriage and political alliances regularly transcending formal ethnic lines. Ethnicity in Afghanistan is essentially pre-nationalist, it is descriptive, not fundamentally operational, except when used to mobilize against a common enemy.

The IEA regime relies on the Pashtun ethnic base and Pashtun nationalism to cement its authority, conflating their Deobandi sectarian ideology with the conservative Pashtun social code (Pashtunwali). While this strategy allowed them to circumvent clan rivalries and unite Pashtun fighters, their leadership remains too overwhelmingly southern Pashtun for the movement to sustain a nationwide appeal among non-Pashtun populations.

The imposition of Pashtun-led, centralized authority in traditionally non-Pashtun regions, the Tajik northeast, the Uzbek northwest, and the Hazara central regions, is perceived not as the establishment of an Islamic order, but as the revival of the despised Pashtun hegemony.

This perception reignites the demand by non-Pashtun groups, which first emerged in the 1990s civil war, to fundamentally break the century-old ethnic hierarchy. Non-Pashtun factions, such as the National Resistance Front (NRF) may be currently disorganized, but the underlying anti-Taliban sentiment remains a deep-seated structural issue, evidenced by dozens of attacks against Taliban targets reported in early 2025 UN-cited report. The rigid enforcement of Kandahar’s authority through centrally appointed governors, a policy that has historically created deep hostility, maintains resentment in regions that grew accustomed to functional autonomy during the Republic era and the 1990s civil war. This is not ideological resistance, it is the pragmatic reaction of local elites whose economic and political interests are being suppressed by a distant, ethnically biased central authority.

The Inevitability of Functional Fragmentation

The most compelling long-term argument against the IEA’s centralized structure stems from the history of Afghan state collapse. Historical trends show that while insurgencies topple established governments, stable replacements arise from civil war and are defined by the ability to manage ethnic interests. The centralized state, designed to prevent fragmentation, is instead the engine of its own demise, as it cannot cope with regional diversity or local expectations for self-rule.

The IEA’s current refusal to countenance the political alternatives identified as crucial for stability; devolving power to elect provincial and district governors, and recognizing political parties to channel competition away from ethnic blocs, guarantees future instability. The absence of legitimate political platforms forces political competition back into non-political ties: family, regional, and ethnic affiliation. This structure forces non-Pashtuns to mobilize along ethnic and regional lines to protect their interests, mirroring the dynamic that led to the bloody civil war of the 1990s.

Currently, the fear among non-Pashtuns is palpable: that the IEA will use its consolidated control to permanently subordinate their communities. The historical warning is more relevant than ever: non-Pashtuns might choose to abandon the unitary state and functionally secede rather than fight another bloody civil war for control of a state that refuses to accommodate them.

The resulting long-term scenario is not a formal political breakup but a functional fragmentation. While the map of Afghanistan may remain intact, the authority of Kabul will decay everywhere outside the southern Pashtun core. Non-Pashtun regions will increasingly govern themselves, raise local revenue, and engage in regional trade relationships (with Central Asia, Iran) independent of the capital’s control. The IEA’s military strength may delay this process, but structural political fragility, the same fragility that caused every regime to collapse since 1901, will ultimately prevail. The IEA has prioritized ethnic and ideological exclusivity over the national pragmatism necessary for long-term survival, thus condemning the Islamic Emirate to a fate as unstable as the centralized monarchies and republics that preceded it.