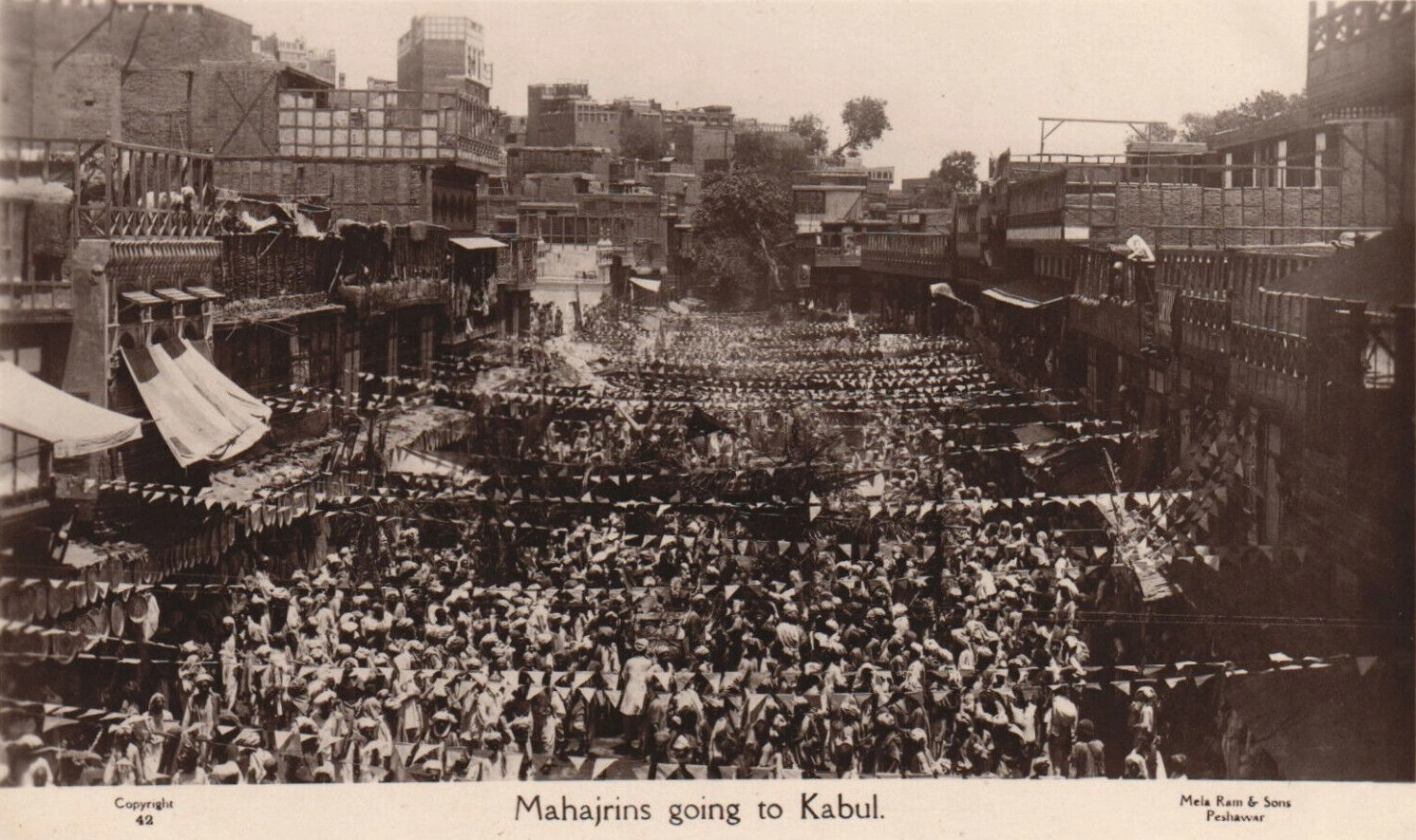

The Tehreek-e-Hijrat (Migration Movement) of 1920 stands as one of the earliest collective political migrations in the Indian subcontinent, an episode that fused faith, politics, and emotion into a singular act of resistance. Emerging from the broader Khilafat Movement, it symbolised Muslim disillusionment with British rule and a spiritual yearning for freedom following the turmoil of the First World War.

As the Khilafat Movement sought to defend the Ottoman Caliphate, the symbolic heart of the Muslim world, the British suppression of dissent through laws such as the Rowlett Act (1919) deepened the sense of injustice among Indian Muslims. Under the influence of religious scholars and activists such as Ghulam Muhammad Aziz (Aziz Hindvi), many began to view British India as Dar-ul-Harb (a land hostile to Islam). In that climate, migration (Hijrat) was interpreted as both a spiritual duty and a political protest: to leave the land of oppression for Dar-ul-Islam, where Islam could be freely practised.

In Sindh, the movement gained organisational form through the establishment of the HijratCommittee under leaders such as Maulana Abdul Karim Dars, Barrister Jan Muhammad Junejo, and Maulana Taj Muhammad Amroti. It was a defining moment in Sindh’s political awakening, the first time the rural poor and peasants, often under the influence of powerful landlords, participated en masse in a political cause.

In July 1920, the first caravan of migrants departed from Larkana, led by Syed Sikandar Ali Shah, reaching Jalalabad soon after. Initially, the Afghan ruler, Amir Amanullah Khan, welcomed the Muhajireen and allotted land for settlement. But as thousands more arrived, many impoverished and unprepared, the Afghan state grew overwhelmed. Within weeks, Amanullah reversed his decision, closing the border and halting further migration. Thousands of Indian Muslims found themselves stranded and destitute on Afghan soil, caught between faith and reality. Despite appeals from Maulana Abul Kalam Azad and other Khilafat leaders, the Afghan government refused to reopen its borders. The movement, fuelled by emotion but lacking foresight, soon collapsed. Leaders like Bacha Khan eventually recognised its futility, and the episode became a sobering lesson in the limits of idealism.

The echoes of that history resonate today. A century later, Pakistan faces similar moral and political dilemmas as it navigates the complex realities of hosting millions of Afghan refugees. Since 1979, Pakistan has provided refuge to generations of Afghans, often despite its own economic hardship and security challenges. According to UNHCR, over 2.8 million Afghans remain in Pakistan as of 2024, a testament to a longstanding tradition of generosity that the UN itself has repeatedly acknowledged.

Yet, when Pakistan began the repatriation of undocumented Afghans in recent years, it faced harsh criticism from abroad. Paradoxically, some of the same nations criticising Pakistan have themselves tightened immigration laws and limited refugee intake. Germany, for instance, had pledged safe relocation for Afghans at risk from the Taliban, yet those programmes have been suspended under stricter immigration policies. Rights groups in Germany now accuse their own government of neglecting its moral obligations, while urging Pakistan, a developing country, to do more. The disparity raises a pressing question: why must nations with constrained means continually shoulder the humanitarian burden that wealthier states increasingly evade?

Similarly, Afghan officials and commentators have increasingly invoked colonial legacies to frame Pakistan as an extension of old imperial structures, an actor complicit in their nation’s historical subjugation. This narrative, however, overlooks a revealing irony in Afghanistan’s own past. The parallel is striking. In 1920, Afghanistan itself struggled to accommodate an unplanned influx of Indian Muslim migrants during the Tehreek-e-Hijrat, despite the religious and emotional solidarity. Today, Pakistan faces a similar dilemma. Having hosted millions of Afghan refugees for decades, it continues to be expected to shoulder this burden with patience and grace, even as its own economy and security strain under pressure. History, therefore, reminds us that no nation is immune to the limits of capacity. The real lesson lies not in reviving past grievances, but in recognising shared struggles and striving for cooperative, humane solutions, rooted in empathy rather than accusation.

In the end, history teaches that survival, not sanctimony, shapes nations. The Tehreek-e-Hijrat remains a reminder of unity, faith, and human resilience, but also of the need for prudence and partnership in the face of crisis. Just as Afghanistan once struggled under the weight of a migration it could not sustain, Pakistan today shoulders a challenge far larger in scale and complexity. To move forward, the world must view refugee responsibility not as a moral contest but as a shared humanitarian commitment, guided by history, but not trapped by it.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own. They do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of the South Asia Times.

![Prime Minister Narendra Modi with External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar at an official event. [Photo Courtesy: Praveen Jain via The Print].](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/20-scaled-e1755601883425-1024x576-1.webp)