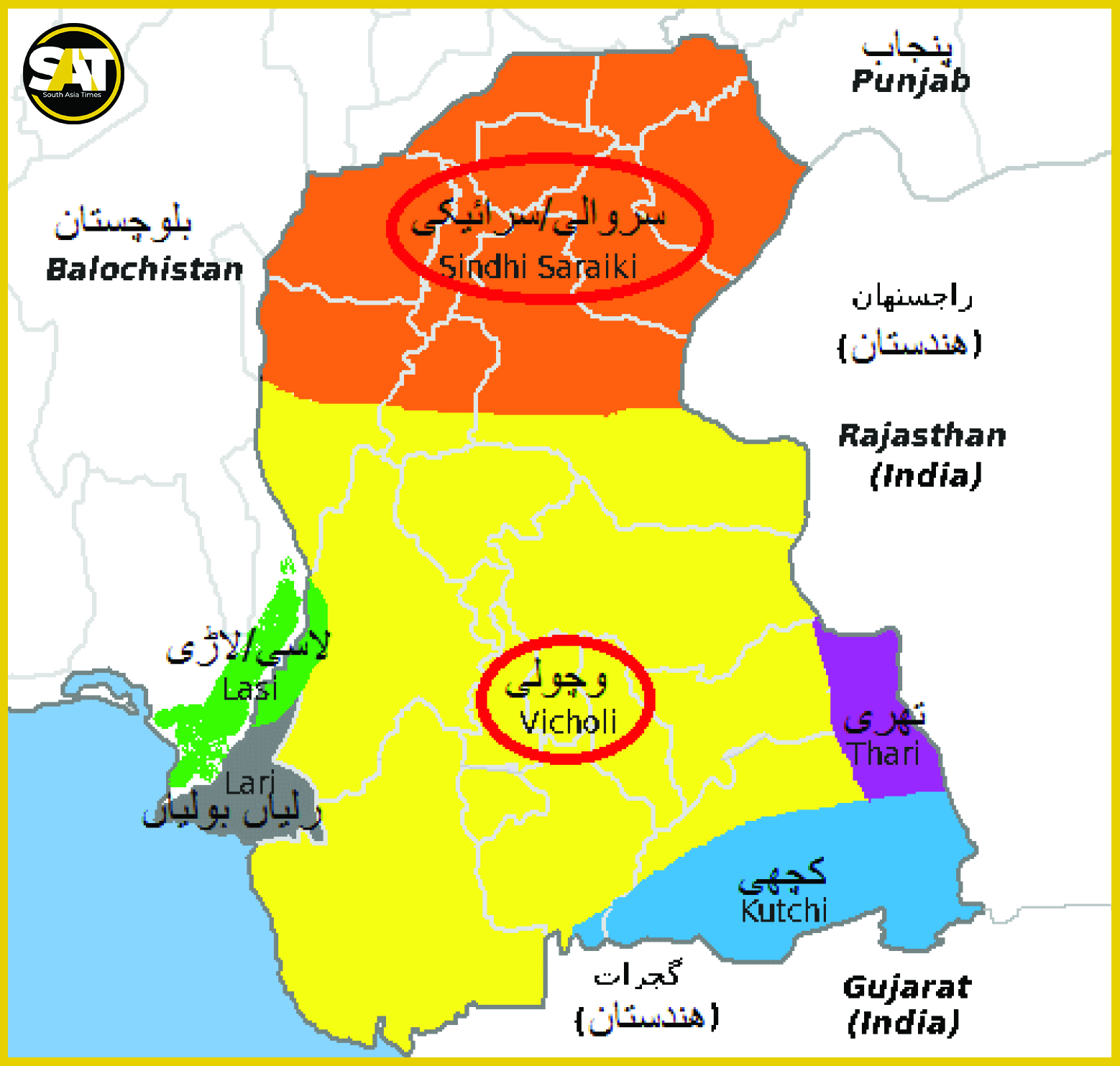

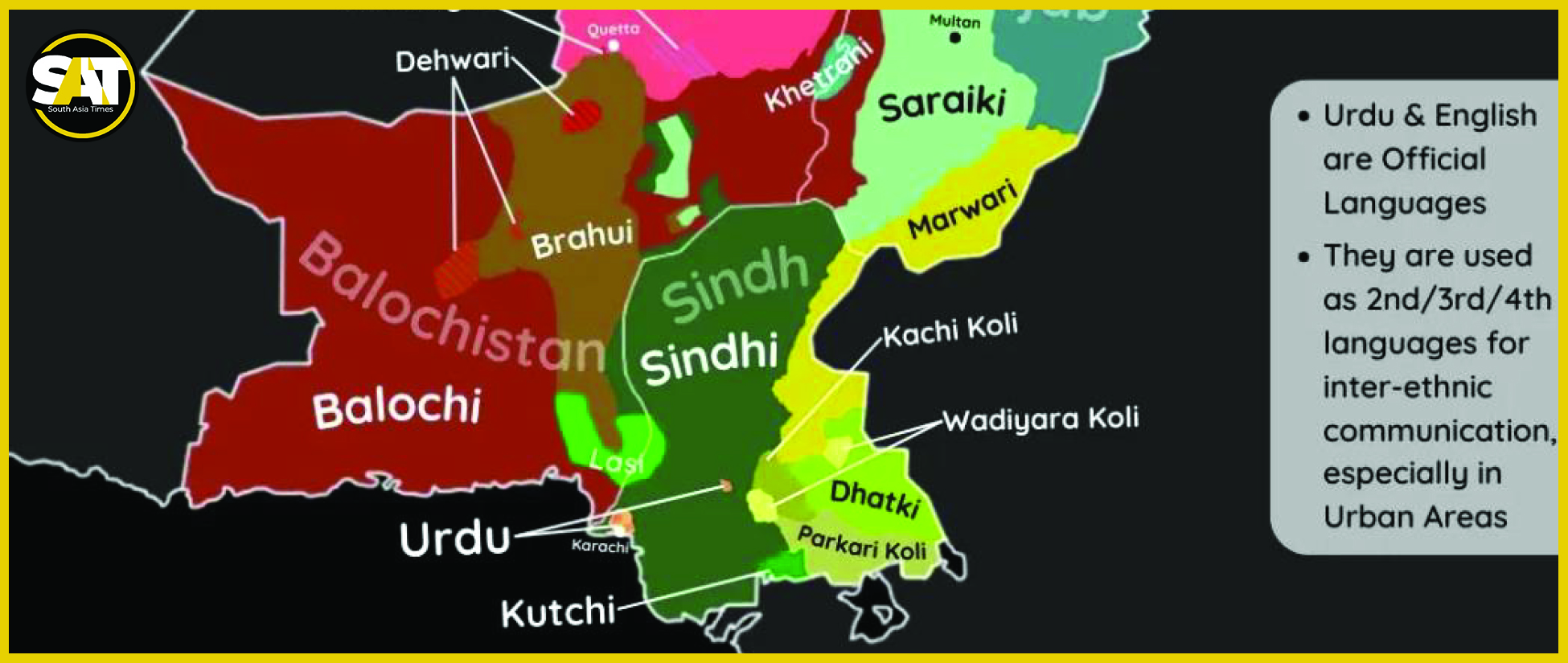

Sindhi, one of the most ancient languages within the Indo-Aryan language family, boasts a rich historical legacy. Over time, it has been documented in various scripts, including Gurmukhi, Khojki, Shikarpuri, and Khudabadi. In contemporary usage, Sindhi employs the Sindhi-Arabic script in Pakistan, which features 52 letters as an adaptation of the Arabic alphabet, and the Devanagari script in India. Additionally, Roman-Sindhi has gained popularity among modern Sindhi speakers for digital communication, such as texting on mobile devices. Within Pakistan’s Sindh province, a notable linguistic divide exists between the northern (Siroli/Saraiki) and southern (Vicholi, often regarded as the standard or recognized Sindhi) varieties. The Vicholi dialect, promoted during British colonial rule for educational and administrative purposes, continues to serve as the official standard in Sindh’s government and institutions today. However, this emphasis on Vicholi has unintentionally or intentionally marginalized other indigenous languages and mother tongues in the province, limiting their speakers’ access to cultural acknowledgment and equitable participation in provincial governance.

Recognizing all the languages spoken in Sindh is crucial for several interconnected reasons. Firstly, it fosters cultural preservation and inclusivity, ensuring that diverse ethnic groups feel valued and represented in society, which in turn promotes social harmony and reduces feelings of alienation. Secondly, official acknowledgment enables better access to education, media, and government services in native tongues, empowering communities economically and politically while preventing linguistic erosion amid globalization and urbanization. Thirdly, it safeguards intangible heritage, such as folklore, poetry, and traditions, which are deeply embedded in these languages and contribute to Sindh’s overall identity. Without such recognition, minority languages risk extinction, leading to a loss of biodiversity in human expression and hindering intergenerational knowledge transfer. Ultimately, embracing linguistic diversity strengthens national unity by celebrating Sindh’s multicultural fabric rather than imposing a monolithic standard.

The following is a comprehensive list of the languages mentioned, including their regional contexts, speaker demographics, and key characteristics:

1. Vicholi/Recognized Sindhi:

This is the standard dialect spoken in southern and central Sindh, particularly around Nawabshah and Hyderabad. It is the benchmark for education, literature, and official use in the province.

2. Siroli/Saraiki:

Predominantly spoken in northern Sindh districts like Ghotki, Khairpur, Naushahro Feroze, Shaheed Benazir Abad, Sukkur, Jacobabad, Kashmore, Larkana, Qamber Shahdadkot, Shikarpur, and Dadu. It emerged as a distinct identity in the 1960s, incorporating local variants such as Multani, Derawi, or Riasti. Saraiki shares much of its vocabulary and structure with Standard Punjabi but differs in phonology, lacking tones, retaining voiced aspirates, and featuring implosive consonants.

3. Dhatki/Thari (also known as Dhatti or Thareli):

Primarily used in Tharparkar and Umerkot in Pakistan, as well as Jaisalmer and Barmer in India, reflecting the cross-border cultural ties in the Thar Desert region.

4. Kutchi Language

Spoken mainly in the Kutch region of Gujarat, India, and the southern parts of Sindh in Pakistan. Influenced by Persian, Arabic, and Portuguese due to historical interactions, it embodies the nomadic and pastoral lifestyles of its speakers. Kutchi is rich in music and poetry that depict everyday activities like farming, fishing, and weaving.

5. Marwari Language

With around 2.5 million speakers in Sindh, Pakistan, it includes about 24 dialects, with Jodhpuri and Jaisalmeri being prominent locally. Written in a modified Arabic script in Sindh, it has ancient roots tied to the Indus Valley inhabitants like the Bheels, Kolhis, and Manghwars, and has mutually influenced Sindhi over centuries.

6. Jadgali Language

Spoken by the Jadgal ethnolinguistic group in Pakistan and Iran, with an estimated 15,600 or more speakers concentrated in Pakistan. As a Sindhi dialect closely related to Lasi, it has historically influenced Balochi and Brahui, and is used in rural areas of Sindh.

7. Lari Language

Used by over 2 million people in southern Sindh, including Karachi, Thatta, Sujawal, and Tando, highlighting its role in urban and coastal communities.

8.Lasi Language (also known as Lassi)

Spoken by the Lasi community in Balochistan regions such as Naseerabad and Lasbela, though it spills into Sindh’s linguistic landscape.

9. Uttaradi

A northern Sindhi dialect spoken in areas like Larkana, Shikarpur, Sukkur, and Kandiaro, distinguished by minor regional variations in usage.

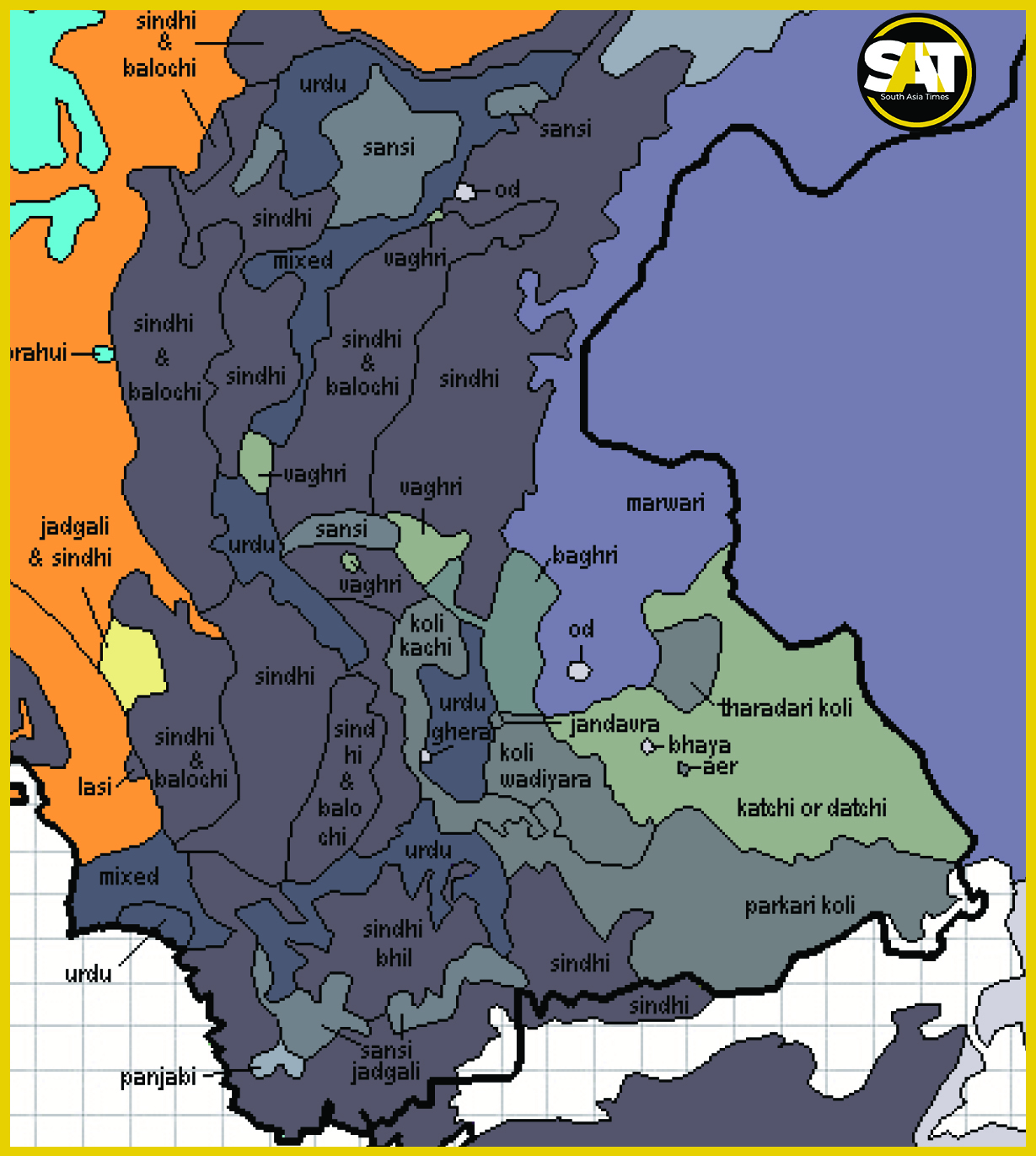

10. Sindhi Bhil

The Sindhi Bhils and Sindhi Meghwars are the speakers of Sindhi Bhil and are Hindu and number around 86,500 in population. They live in Balochistan and Sindh, while there are diasporas in Gujarat and Delhi in India due to the Partition of India. Sindhi Bhil has four dialects. The most spoken is Badin which has around 10,000 speakers. It is spoken in the city of Badin and also Matli. Other dialects include Mohrano, Nuclear Sindhi Bhil, and Sindhi Meghwar. Mohrano is spoken in Tando Allahyar.

11. Sansi Bhil

Sansi Bhil is a language spoken in Sindh by the Bhil ethnic group. The Sansi Bhil inhabit the rural areas of Pakistan’s Sindh Province. They are classified as a Bhil ethnic group, and their native language, Sansi, belongs to the Indo-Aryan linguistic family. Most of the Sansi Bhil are bilingual, speaking both Sansi and Western Punjabi.

12. Vaghri Language

Vaghri is a Indo-Aryan language of Sindh, Pakistan. It is closely related to Wagdi, Bauria, and Gujarati. The speakers of Vaghri are predominantly Hindu. The regional languages have been key in promoting cultural diversity and harmony in Sindh. Its literature, poetry, and music are the most dominating cultural expressions. They have contributed to the socio-economic development of the region. The Vaghri ethnic group in Pakistan are found mainly in the districts of Umerkot and Tharparkar.

13. Wadiyara Koli

Wadiyara Koli is an Indo-Aryan language of the Gujarati group. It is spoken by the Wadiyara people, who originate from Wadiyar in Gujarat; many of whom are thought to have migrated to Sindh in the early twentieth century, following the onset of famine. The Wadiyara people are affiliated with the Bhil people and Koli people, but are generally more inclined towards associating themselves with the Koli; they are often regarded as a subgroup of the latter.

14. Parkar Koli

The Parkari Koli language (sometimes called just Parkari) is an Indo-Aryan language mainly spoken in the province of Sindh, Pakistan. It is spoken in the southeast tip bordering India, in the Tharparkar District, Nagarparkar. Most of the lower Thar Desert, west as far as Indus River, bordered north and west by Hyderabad, to south and west of Badin.

15. Kachi Koli

Kachi Koli is an Indo-Aryan language spoken in India. There is a small population of Koli who live across the border in eastern Sindh province in neighbouring Pakistan. Part of the Gujarati subfamily, Kachi Koli is closely related to Parkari Koli and Wadiyara Koli.

Therefore, in order to ensure the linguistic diversity and cultural inclusivity of Sindh province, the Sindhi Language Authority (SLA), as an autonomous body under the Government of Sindh’s Department of Culture, Tourism, and Antiquities, should formally recognize the array of regional languages and dialects—such as Siroli/Saraiki, Dhatki/Thari, Kutchi, Marwari, Jadgali, Lari, Lasi, Uttaradi, Sindhi Bhil, Sansi Bhil, Vaghri, Wadiyara Koli, Parkar Koli, and Kachi Koli—as integral components of Sindh’s multilingual heritage, extending beyond the current focus on Vicholi (the recognized standard Sindhi). This recognition could involve establishing dedicated research, documentation, and preservation programs within the SLA, including digital archives, literature development, and community engagement initiatives to prevent their marginalization amid the dominance of Vicholi Sindhi and English. Simultaneously, the Sindh (Teaching, Promotion and Use of Sindhi Language) Act, 1972—which originally designated Sindhi as the official provincial language and mandated its teaching in educational institutions—should be amended to incorporate these languages through targeted provisions, such as optional curricula in schools for mother-tongue education, multilingual government services in relevant districts, and funding for media and cultural events that promote them alongside Vicholi Sindhi. Such incorporation, building on the Act’s application clauses that already emphasize non-discrimination (as clarified in the 1972 Application Act and subsequent amendments like those in 1990), would foster equitable access to education and governance, reduce ethnic tensions, and preserve Sindh’s rich tapestry of indigenous expressions for future generations, ultimately strengthening provincial unity.

Statistics Displaying Spoken Language Diversity in Sindh

The provided statistics on linguistic diversity in Sindh province, drawn from the 2023 Pakistan Population and Housing Census conducted by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS), underscore the province’s role as a vibrant multicultural mosaic within Pakistan, reflecting centuries of migration, trade, and historical influences along the Indus River valley and its borders with India, Balochistan, and Punjab. Released in phases, with detailed language data disseminated in July of 2024, the census captured a provincial population of approximately 55.7 million, revealing at least 16 distinct languages spoken by its communities—a figure that aligns with the “rich tapestry” of Indo-Aryan, Iranian, and Dardic linguistic families prevalent in the region, though the total number of mother tongues in Sindh may exceed this when accounting for dialects like those discussed in prior contexts (e.g., Lari, Kutchi, or Jadgali).

The term “Sindhi” in the census is employed as an all-encompassing category for the primary language spoken by approximately 33.462 million people (about 60% of population) in Sindh province, without distinguishing between its various dialects or the numerous other regional languages spoken in the region, such as Siroli/Saraiki, Dhatki/Thari, Kutchi, Marwari, Jadgali, Lari, Lasi, Uttaradi, Sindhi Bhil, Sansi Bhil, Vaghri, Wadiyara Koli, Parkar Koli, and Kachi Koli. This broad categorization likely groups the standard Vicholi dialect—recognized officially under the Sindh (Teaching, Promotion and Use of Sindhi Language) Act, 1972—alongside its regional variants and related Indo-Aryan languages under a single “Sindhi” label, reflecting a methodological choice to prioritize major linguistic identities over granular distinctions. This approach obscures the province’s rich linguistic diversity,

Sindhi, encompassing all other dialects official provincial language under the Sindh (Teaching, Promotion and Use of Sindhi Language) Act, 1972, dominates with 33.462 million speakers (about 60% of the population), symbolizing the core ethnic Sindhi identity rooted in ancient Indus Valley heritage and Sufi traditions. However, the significant presence of Urdu (12.409 million speakers, or 22%), largely tied to post-1947 Muhajir (Urdu-speaking migrant) communities from India, highlights Sindh’s urban transformation, particularly in Karachi, Pakistan’s economic powerhouse and the nation’s most linguistically diverse urban center. Karachi’s seven districts alone host over 10 million Urdu speakers alongside substantial Pashto (2.752 million, reflecting Afghan refugee influxes and Pashtun labor migration), Punjabi (1.645 million, from neighboring Punjab), and Sindhi (2.264 million) populations, illustrating how economic opportunities in ports, industries, and services have drawn internal and cross-border migrants, exacerbating ethnic tensions and political dynamics in a province historically marked by feudal isolation and resistance to central authority, as seen during Mughal and British eras. Other languages like Pashto (2.955 million province-wide, third-ranked), Punjabi (2.265 million), Balochi (1.208 million), and Saraiki (913,418)—the latter overlapping with northern dialects like Siroli—further evidence Sindh’s peripheral yet interconnected status, influenced by proximity to Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, while smaller groups such as 830,581 Hindko speakers, 265,769 Brahui speakers, 53,249 Kashmiri speakers, 57,059 Mewati speakers, 22,273 Shina speakers, 27,193 Balti speakers, 14,885 Kohistani speakers, 777 Kailashi speakers point to diaspora communities from northern Pakistan, often marginalized in rural or desert areas like Tharparkar.

This diversity, encompassing over 1.151 million speakers of “other” languages, not only enriches Sindh’s cultural heritage—evident in festivals, poetry, and crafts like Ajrak—but also poses challenges for policy, such as equitable education and governance under the Sindhi Language Authority, where the dominance of Vicholi Sindhi has historically sidelined regional variants, potentially fueling social inequities amid urbanization (Sindh’s urban share at 54%) and a national population growth rate of 2.55%. In a broader Pakistani context, where Punjabi leads nationally at 37%, these figures emphasize Sindh’s unique blend of indigenous resilience and migrant integration, informing resource allocation via the National Finance Commission and addressing preservation needs to prevent linguistic erosion in the face of Urdu and English as national lingua francas.

Understanding Socio-Political and Class Structure in Sindh

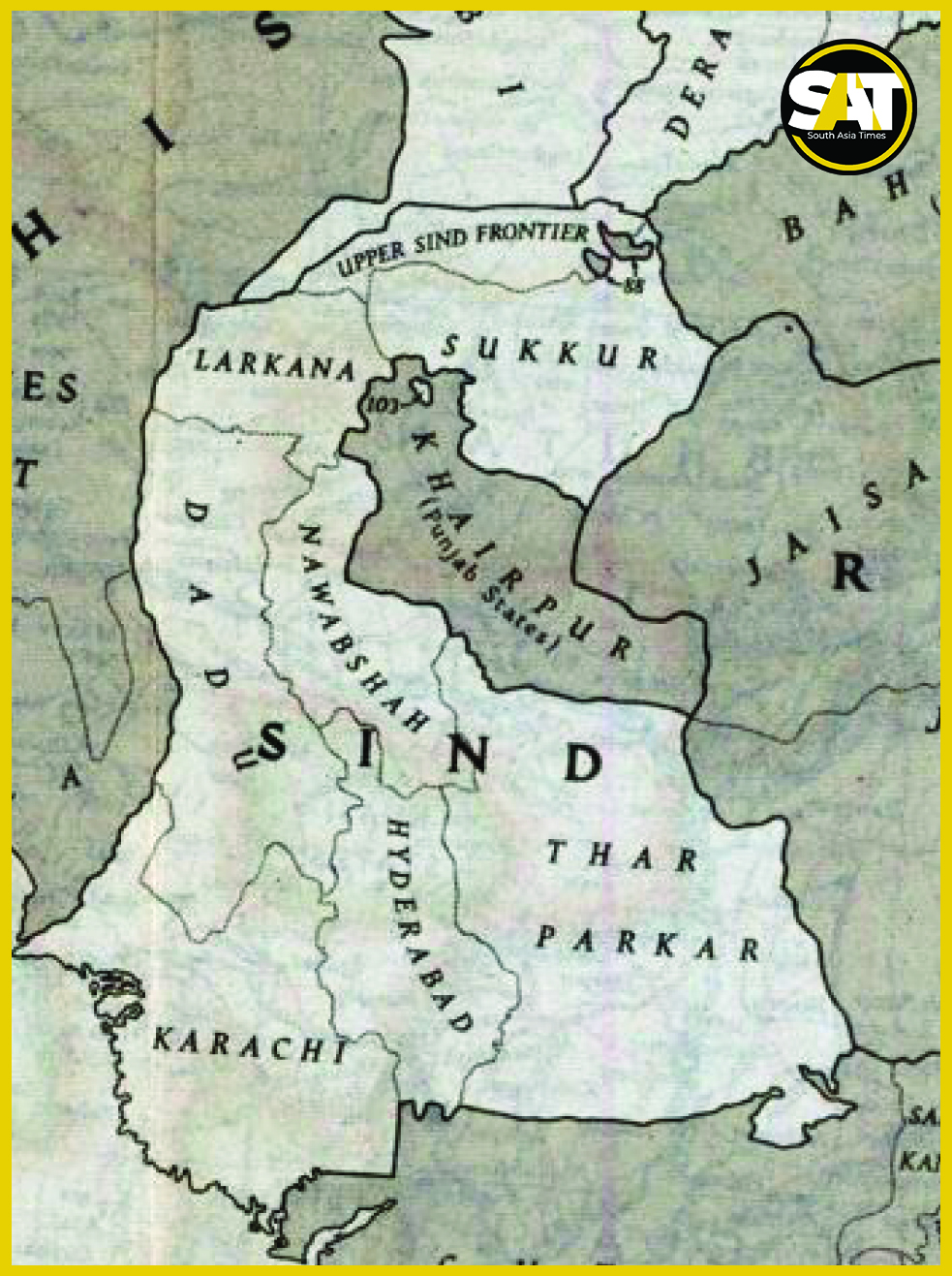

The social and political fabric of Sindh has long been shaped by its geographical and historical isolation, fostering a distinct identity marked by feudal oppression, the influence of pirs (religious guides), and resistance to external control. Throughout Mughal rule, Sindh’s peripheral status allowed local clans to resist centralized revenue demands, resulting in a unique socio-economic structure divergent from regions like Punjab or the North West Frontier Province. Under British colonial rule from 1843, Sindh’s integration into the Bombay Presidency left the power of local elites largely intact, reinforcing a repressive feudal system established during the Talpur era (1782–1843), where powerful individuals became de facto landowners, creating a fiefdom-like structure rather than a centralized state. This entrenched feudalism, coupled with minimal colonial intervention in agrarian policy, perpetuated socio-economic disparities and limited modernization outside urban centers like Karachi, which was developed as a port city. Politically, Sindh operated under a semi-independent judicial and governance system, with many Bombay Presidency laws not applying, further isolating it from broader colonial frameworks. Socially, the dominance of feudal lords and pirs stifled broader societal progress, while the region’s deserts, mountains, and swamps reinforced its reputation as a “backwater,” disconnected from mainstream British India, shaping a modern history distinct from other Pakistani regions.

Even today despite the Sindh government spending billions of rupees on social protection programs, poverty remains deeply entrenched in the province’s rural areas.

According to official statistics obtained by the Express Tribune, the Sindh government has spent nearly Rs20 billion in five years on a single poverty alleviation project, yet at least 70 per cent of the population across ten districts is still living below the poverty line. The Multi-Dimensional Poverty Index compiled by the Planning and Development Department’s Research and Training Wing has shown that across five districts, more than 80 per cent of people are stuck in poverty. Surprisingly, poverty levels in these five districts exceed those in Tharparkar. The worst-affected districts are Thatta, Sajawal, Kashmore, Badin, and Jacobabad.

The survey also revealed alarming rates of malnutrition among women in these districts. While 50 per cent of women in Tharparkar suffered from nutritional deficiencies, the rate was even higher in the five poorest districts. In fact, 66 per cent of women in Thatta and Jacobabad, 59 per cent in Kashmore, 56 per cent in Badin, and 51 per cent in Sajawal were living with malnutrition.

Conclusion

The linguistic and cultural diversity of Sindh, comprising at least 16 distinct languages according to the 2023 Pakistan Census, illustrates its historical significance as a crossroads of civilizations. However, the generalized classification of “Sindhi” in official statistics obscures the intricate array of dialects and languages, such as Siroli/Saraiki, Dhatki/Thari, Kutchi, Marwari, Jadgali, Lari, Lasi, Uttaradi, Sindhi Bhil, Sansi Bhil, Vaghri, Wadiyara Koli, Parkar Koli, and Kachi Koli, thereby jeopardizing their recognition amidst the predominance of Vicholi Sindhi. This linguistic oversight reflects the province’s socio-political difficulties, where historical feudalism, established during the Talpur and British periods, along with the persistent influence of local elites and pirs, has sustained isolation and inequality, especially in rural regions where over 70% of the population in districts such as Thatta and Jacobabad lives in poverty. To safeguard Sindh’s multicultural history and rectify these imbalances, the Sindhi Language Authority and the Sindh (Teaching, Promotion and Use of Sindhi Language) Act, 1972, require reform to officially acknowledge and promote all regional languages via education, media, and governance. These initiatives would promote inclusivity, alleviate ethnic tensions, and empower marginalized communities, safeguarding Sindh’s rich linguistic and cultural heritage while tackling systematic poverty and social exclusion for a more equitable future.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own. They do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of the South Asia Times.

References

- Ahdi Hassan, Assimilation and incidental differences in Sindhi language, Eurasian Journal of Humanities (2016), Vol. 2. Issue 1. ISSN: 2413-9947

- Jhatial, Z., & Khan, J. (2021). Language shift and maintenance: The case of Dhatki and Marwari speaking youth. Journal of Communication and Cultural Trends, 3(2), 59–76.

- Ghulam Murtaza Naz, (The Lexical and Phonetic Similarities of Marwari Language with Sindhi

- Sindhi Language Authority, About Us

- THE SIND (TEACHING, PROMOTION AND USE SINDHI LANGUAGE) ACТ, 1972.

- Census shows rich lingual tapestry in Sindh, The Express Tribune

- Adeel Khan, PAKISTAN’S SINDHI ETHNIC NATIONALISM Migration, Marginalization, and the Threat of “Indianization”

- India, Political Subdivisions of India, National Geographic Series (Reverse of India-Myanmar), 1946, 1:6 000 000. National Geographic Society for the National Geographic Magazine, 1946.

- Razzak Abro, Poverty continues to plague rural Sindh, The Express Tribune

![Prime Minister Narendra Modi with External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar at an official event. [Photo Courtesy: Praveen Jain via The Print].](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/20-scaled-e1755601883425-1024x576-1.webp)