The relationship between India and Pakistan has been defined by different historical and territorial disputes, but none is perhaps as critical to the very survival of the latter as the politics of transboundary rivers. Pakistan’s agricultural economy and a significant portion of its population are sustained by the Indus River system, which originates in the Himalayas and flows primarily through Indian territory before entering Pakistan. For decades, this geographic reality has fueled a persistent sense of vulnerability in Islamabad, leading to concerns that India, as the upper riparian state, could use its control over the shared rivers as a strategic tool. From the tumultuous days of partition in 1947 to the ongoing tensions of the 21st century, water has become a potent symbol of geopolitical leverage, a dynamic that demands a more proactive role from the international community, particularly the United Nations.

The Genesis of a Dispute: From Partition to a Treaty

The partition of British India in 1947 created an immediate and complex water crisis. The Radcliffe Line, drawn to divide the subcontinent, arbitrarily cut across the Indus river system, leaving the headwaters and source rivers of Pakistan’s major lifelines under Indian control. The initial Inter-Dominion Accord of 1948 was a temporary measure, but it became clear that a permanent solution was needed to avert potential conflict. This led to years of negotiations, largely brokered by the World Bank. The effort culminated in the signing of the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) in 1960, a landmark agreement that has been hailed as one of the most successful water-sharing accords in modern history.

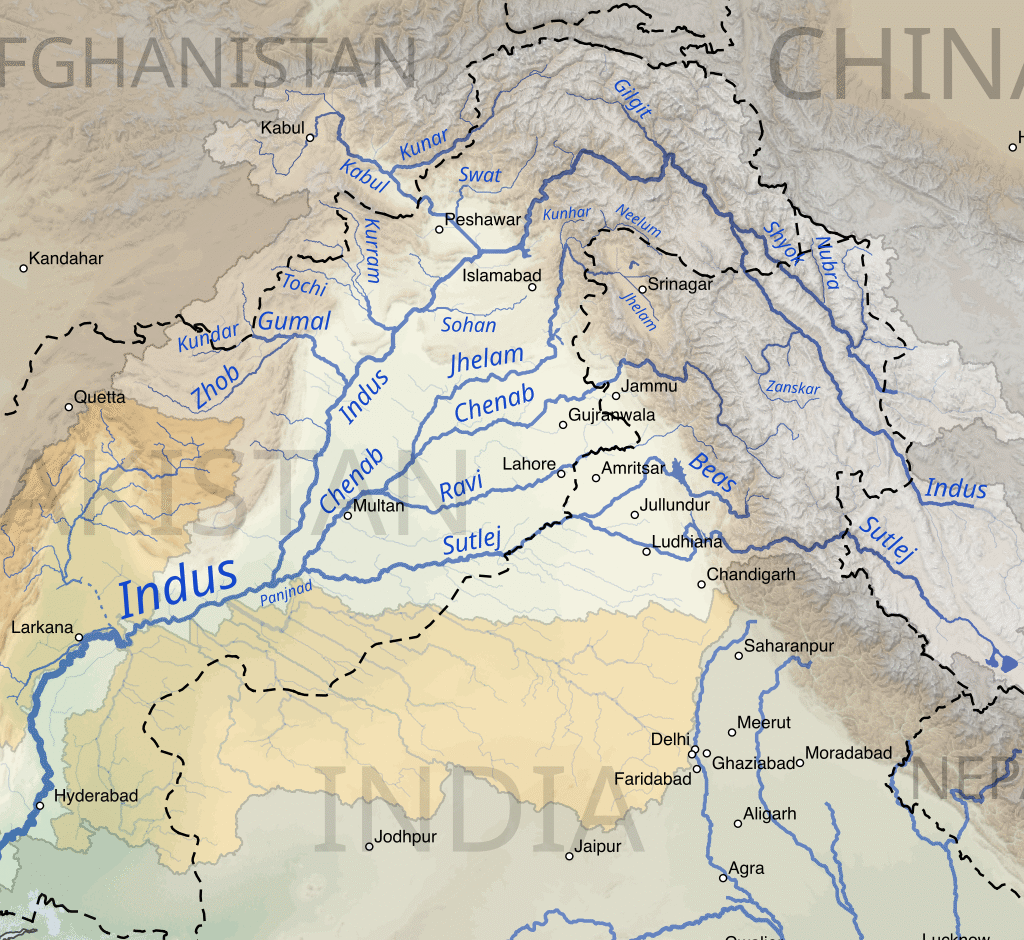

Under the IWT, the rivers of the Indus Basin were divided. India was granted exclusive rights to the waters of the eastern rivers—the Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej—while Pakistan received control over the “western rivers—the Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab. The treaty also established a Permanent Indus Commission to serve as a channel for communication and to resolve potential disputes. Despite its durability, the treaty was signed under the assumption of a cooperative future, a vision that has been increasingly challenged by escalating tensions and India’s growing water infrastructure projects.

The Spectre of Water Blackmail: The Upstream-Downstream Dynamic

For Pakistan, the most significant source of anxiety has been India’s construction of hydropower projects on the western rivers, which, according to the IWT, are designated for Pakistan’s unrestricted use with specific exceptions for non-consumptive purposes. While India maintains that these projects are fully compliant with the treaty’s technical specifications, Pakistan has consistently expressed concern that the cumulative effect of these dams could grant India the ability to regulate or even restrict the flow of water, especially during critical periods. The projects on the Chenab and Jhelum rivers, such as the Kishenganga and Ratle hydroelectric plants, have been at the center of this controversy. This narrative has given rise to the term “water terrorism” in Pakistan, reflecting the profound fear that water could be weaponized to cripple its economy and destabilize its society.

This concern is amplified by India’s major canal projects. Notably, the Indira Gandhi Canal, one of the world’s largest canal systems, diverts significant volumes of water from the Sutlej and Beas rivers to irrigate vast swathes of arid land in the states of Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan. While these are eastern rivers, the existence of such large-scale water diversion infrastructure raises broader concerns in Pakistan about India’s capacity and political will to manage the entire basin system responsibly. On western rivers, India is conducting feasibility studies on canals that can divert water from Jhelum and Chenab to Indian areas, a clear act of water terrorism.

A disruption in water flow could lead to a catastrophic decline in agricultural output, affecting food security, employment, and the livelihoods of millions. The use of water as a political tool exacerbates a deep-seated mistrust, making it difficult to address the broader challenges of climate change and water scarcity that affect both nations. This dynamic came to a head in April 2025, when India unilaterally suspended the IWT. This action, unprecedented in the treaty’s six-decade history, was viewed by Pakistan as the ultimate act of water blackmail, transforming a long-simmering dispute into an open political confrontation.

A Looming Conflict: The Human Element

The potential for conflict is not merely theoretical, it is rooted in the demographic and economic realities of Pakistan. The provinces of Sindh and Punjab, which are the most populous in the country and constitute its agricultural heartland, are critically dependent on the Indus Basin for their livelihoods. Millions of farmers and their families rely on a predictable water supply for irrigation, which accounts for over 90% of the nation’s total water consumption. A significant or prolonged reduction in water flow, whether through a deliberate stoppage or the mismanagement of upstream dams, could lead to a severe agricultural crisis. This would not only result in widespread food shortages and economic collapse but also ignite social and political unrest.

The fear is that a water crisis could force people and the government to take desperate measures, potentially escalating the dispute from a diplomatic spat into a military confrontation. In a region already fraught with tension, where both nations possess nuclear weapons, a dispute over a life-sustaining resource like water poses an existential threat to regional peace.

The United Nations and International Legal Frameworks

The United Nations has a vested interest in the peaceful resolution of transboundary water disputes, recognizing that water scarcity and conflict are major threats to global peace and security. The UN General Assembly and the Human Rights Council have affirmed the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation. Furthermore, international law provides a framework for such disputes. The 1997 UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses provides a cornerstone for transboundary water management. It establishes two fundamental principles: “equitable and reasonable utilization” and the “obligation not to cause significant harm.” While India is not a signatory to this convention, these principles are widely considered customary international law, binding on all states.

Historically, the UN’s formal involvement in the Indus dispute has been limited. The World Bank, served as the primary mediator and is a signatory to the IWT. While the treaty includes robust dispute resolution mechanisms, a neutral expert for technical issues and a Court of Arbitration for broader disputes, the process has been mired in disagreements. The Court of Arbitration, established under the IWT, quickly responded to India’s suspension. It rendered a supplemental award in June 2025, reaffirming its competence over the dispute and holding that the treaty does not provide for a unilateral suspension or abeyance. This ruling was a significant observation against India’s unilateral action and a strong affirmation of the treaty’s binding nature.

The UN’s experience in other regions, however, offers a precedent for a more assertive role. In the Nile Basin, for example, the UN has supported dialogue and cooperation between riparian states like Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia. Similarly, in the Jordan River Basin, the UN has acted as a facilitator in water-sharing agreements. These examples demonstrate that the UN possesses the expertise and diplomatic tools to intervene in a neutral capacity. The UN’s convening power and the authority of its International Court of Justice could be instrumental in holding states accountable to international legal principles.

A Call for Action: The UN’s Potential Role

Given the escalating tensions and the existential nature of the water dispute for Pakistan, a more direct and assertive role for the UN is essential. Firstly, the UN could initiate a high-level, independent commission to thoroughly investigate and monitor the flow of the Indus Basin rivers. This would provide objective, transparent data to counter allegations of water manipulation and build trust between the two sides. Secondly, the UN could use its diplomatic channels to urge both India and Pakistan to honor their treaty obligations and to engage in good-faith negotiations to address the new challenges posed by climate change and a growing population.

Most importantly, the UN should consider the water dispute not merely as a bilateral issue, but as a matter of regional peace and security. A sudden reduction of water flow could be a trigger for a humanitarian crisis, which could, in turn, escalate into a full-blown military confrontation between two nuclear-armed powers. By making water security a central pillar of its regional peace-building strategy, the UN could help shift the narrative from one of conflict to one of cooperation, where shared resources become a basis for mutual benefit rather than a tool for intimidation.

The Path Forward

The Indus Waters Treaty, once a beacon of international cooperation, now faces its most significant challenge. The allegations of water blackmail and the unilateral actions of recent years underscore the fragility of the agreement and the urgent need for external oversight. For Pakistan, the issue is not merely about water, it is about national security, economic stability, and the fundamental right to existence. The UN, with its mandate to maintain international peace and security, cannot afford to remain a passive observer. By leveraging international law, providing a neutral platform for dialogue, and actively monitoring the situation on the ground, the UN can help ensure that the rivers of the Indus Basin remain a source of life and not a prelude to conflict. The path forward lies in proactive diplomacy, and the UN is uniquely positioned to lead the way.