The Durand Line, the 2,670-kilometer border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, is a primary source of tension between the two countries. Unrecognized by any Afghan government, including the current Taliban regime, but internationally recognized, the line divides the homeland of the Pashtuns and remains one of the region’s most volatile frontiers. It is a frequent flashpoint for cross-border shelling, militant infiltration, and diplomatic crises. This backgrounder explains the line’s colonial origins, the complex legal dispute it fuels, and its enduring impact on regional stability and the modern conflict.

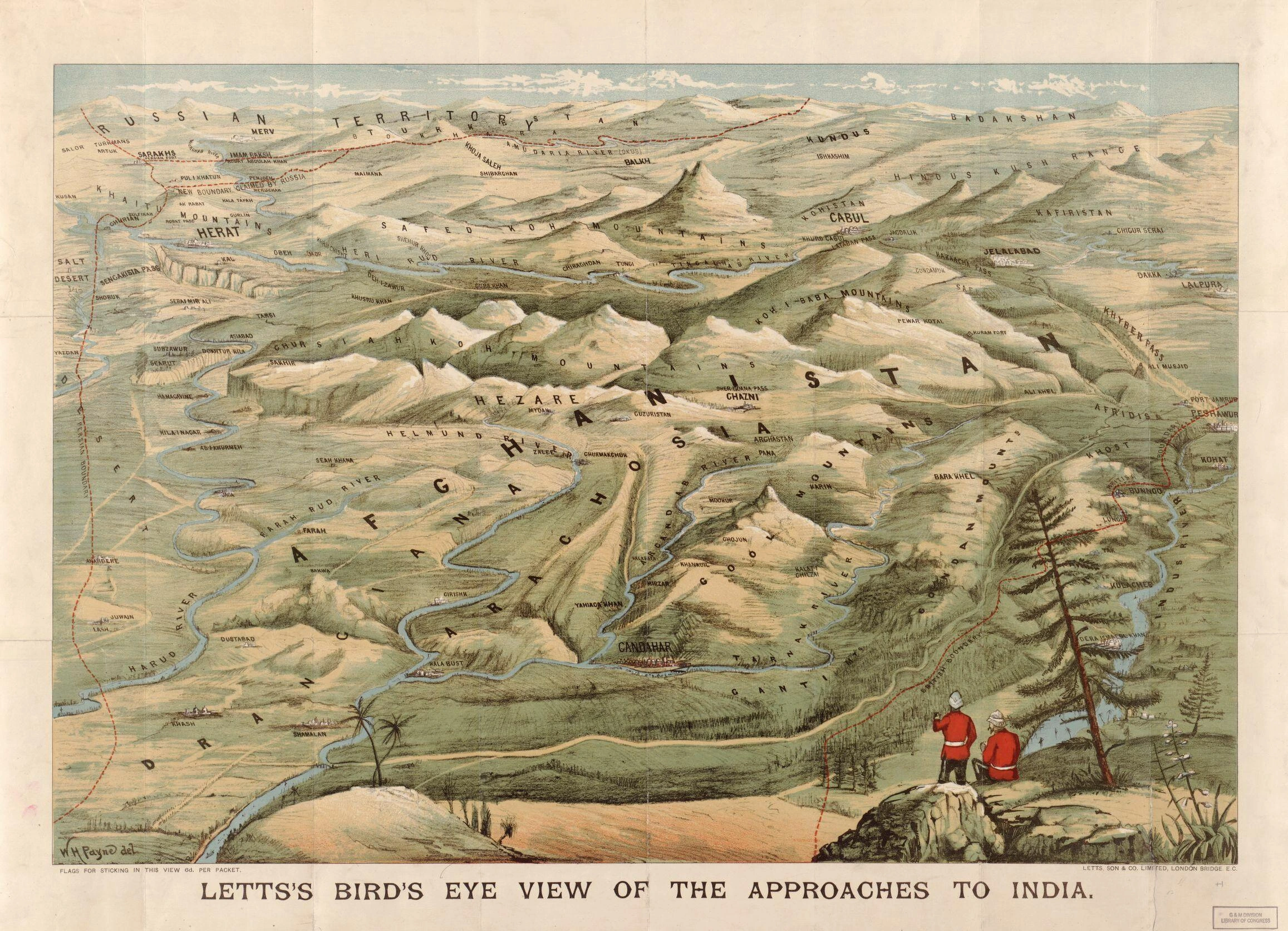

The Durand Line is a product of the 19th-century Great Game, a long and shadowy strategic rivalry between the British Empire (controlling India) and the Russian Empire for influence in Central Asia. As the Russian Empire steadily conquered the khanates of Central Asia, and Britain expanded its control northwest from the Indian subcontinent, Afghanistan was caught between them. Its formidable geography, dominated by the Hindu Kush mountains, made it the critical buffer state, the natural gateway to India that both powers sought to control, or at least deny to the other.

The Great Game and Britain

Britain’s primary objective was to prevent a Russian invasion of India through Afghanistan’s high passes, such as the Khyber. This fear, bordering on paranoia, dictated British policy in the region for a century and led to repeated interventions. To secure this aim, Britain fought two major wars in Afghanistan, both intended to install a pliant ruler rather than to rule the country directly.

- First Anglo-Afghan War (1839-1842): This war began with a British invasion and the installation of their preferred ruler, Shah Shuja. However, it ended as a catastrophic failure. A popular uprising led to a disastrous winter retreat from Kabul, during which the army of William Elphinstone was annihilated. Nearly 16,000 soldiers and camp followers were killed. While Britain did send an Army of Retribution later in 1842 to inflict brutal reprisals, destroy parts of Kabul, and free prisoners, the campaign was punitive, not strategic.

- Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878-1880): This conflict was launched after the Afghan Amir, Sher Ali Khan, refused a British diplomatic mission while welcoming a Russian one, a move Britain saw as a direct threat. This time, the British were more successful militarily and achieved their strategic aim with the 1879 Treaty of Gandamak. This treaty, signed by the defeated Amir Yaqub Khan, was a turning point. It forced the Afghan Amir to cede control of all his foreign policy to the British government. This made Afghanistan a protectorate.

The Unruly Frontier

With Afghanistan’s foreign relations under its control, Britain’s next goal was to manage the border region itself. This area was inhabited by Pashtun tribes who launched frequent raids into settled areas. These tribes lived by their own ancient code, Pashtunwali, and owed little practical allegiance to the Amir in Kabul or the British in India.

This situation created a fierce debate among British strategists. Some favored a Close Border Policy, arguing Britain should fortify the edge of the Indus plain and not get drawn into the tribal hill country. But the advocates of the Forward Policy won out. They argued that Britain must push its influence and administrative control directly into the tribal territories to subdue them and create a clear, defensible line. They wanted to transition from managing a vague, porous frontier (a zone of influence) to defending a hard border (a political line). This policy created the political and military necessity for a formal demarcation, which led to the 1893 negotiation.

The Durand Line Agreement

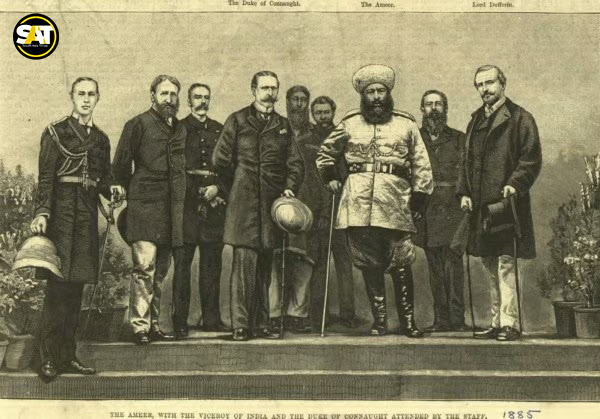

The border was formally established by an agreement signed on November 12, 1893, in Kabul. The signatories were Sir Mortimer Durand, the Foreign Secretary of British India, and Amir Abdur Rahman Khan, the ruler of Afghanistan.

Amir Abdur Rahman Khan, known as the Iron Amir, was a ruthless and pragmatic leader. He had been brought to power by the British after the Second Anglo-Afghan War and was heavily reliant on British subsidies and weapons to consolidate his own rule. He was in the process of brutally suppressing internal rebellions to forge the modern Afghan state.

The Amir was under immense pressure. The British were insistent on a defined border, and the Russians were simultaneously pressuring him from the north (a process that would lead to the Anglo-Russian demarcation of Afghanistan’s northern border in 1895). Caught between two empires, the Amir saw the agreement as a necessary evil. It would secure his vital British subsidy, which funded his state-building project. He may also have seen it as a way to finally get the British to recognize his sphere of influence and stop their Forward Policy incursions into territories he considered his own.

The agreement itself was shockingly brief with its core clause stating that the Amir “agrees that he will at no time exercise interference in the territories lying beyond this line on the side of India.” Britain, in return, affirmed it would not interfere on his side. The agreement also included a significant increase in the Amir’s subsidy and recognized his control over certain territories, like Asmar and the Waziristan valley.

Key Provisions of the Agreement

The one-page 1893 agreement had seven clauses:

- The agreement stipulated that a boundary line would be demarcated from Wakhan in the north to the Persian border in the west, and that both sides would send commissioners to lay it out.

- The British government affirmed it would not exercise interference in the territories lying beyond this line on the side of Afghanistan.

- Amir Abdur Rahman Khan agreed, on behalf of himself and his successors, not to exercise interference in the territories lying beyond this line on the side of India.

- The British agreed to cede the Birmal area to Afghanistan, while the Amir agreed to cede Chaman in Balochistan to British India. (This clause, along with others, was modified by later demarcations, such as the transfer of Asmar to Afghanistan).

- The British government agreed to increase the Amir’s annual subsidy from 12 lakhs (1,200,000) of rupees to 18 lakhs (1,800,000).

- The Amir and his successors were granted the freedom to import munitions of war for state purposes through British India. This was a crucial concession, giving the landlocked state access to modern weaponry.

- The final clause simply stated the agreement was written in both English and Persian and signed by both parties.

Demarcation and the 100-Year Myth

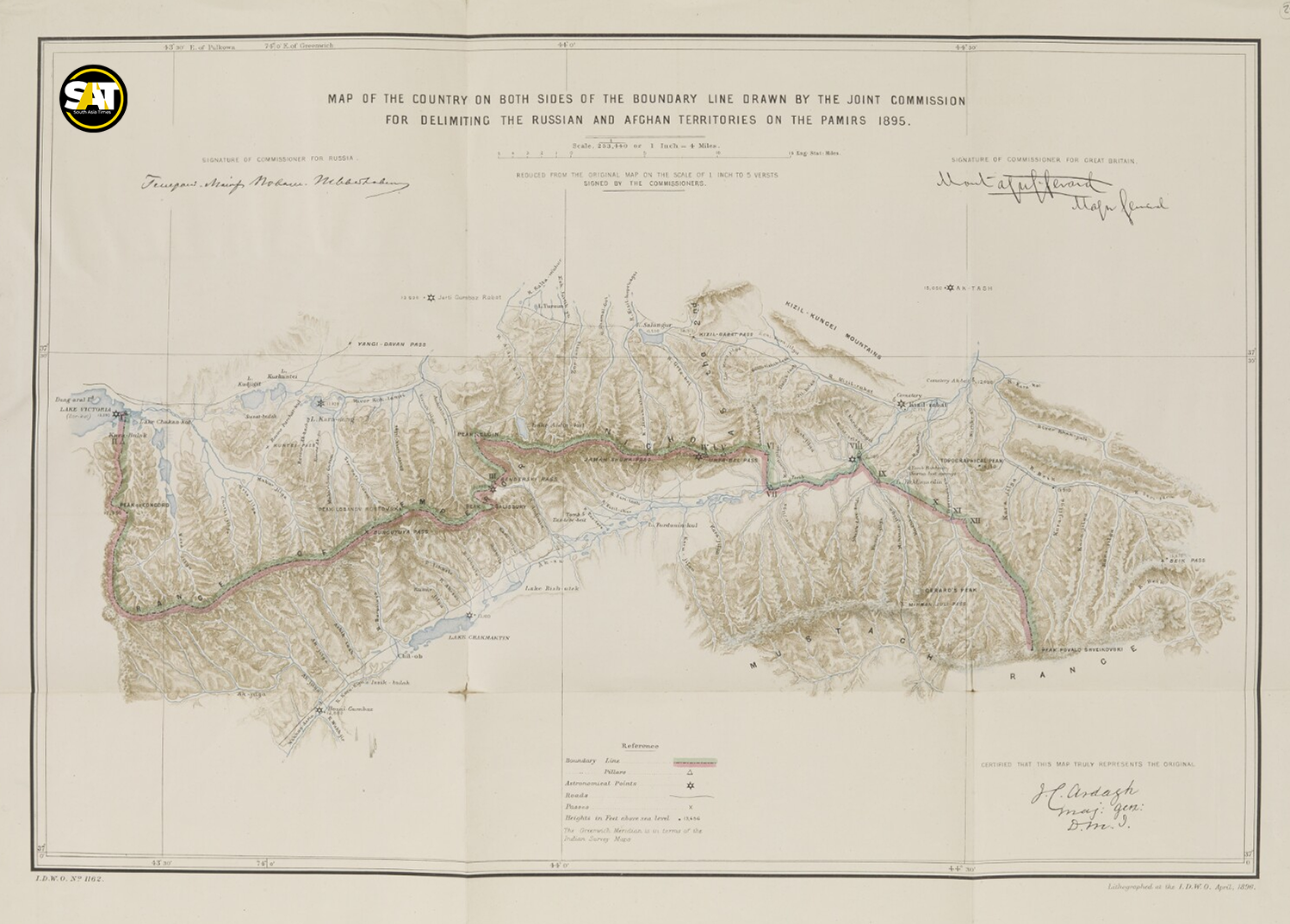

Following the 1893 agreement, the demarcation was carried out by joint Anglo-Afghan commissions from 1894 to 1896. This consensual process translated the one-page agreement onto the terrain, establishing a defined border. While this joint process was successful, the resulting line in some areas intersected with traditional tribal lands and settlement patterns, creating a grievance for Pashtuns who had previously moved freely across the region.

A central element of Afghanistan’s modern challenge to the border is the “100-Year Myth.” This is a persistent and widely held claim from the Afghan side, that the 1893 agreement was a 100-year lease that expired in 1993. This narrative became a cornerstone of Afghan nationalist rhetoric.

However, from a textual and legal standpoint, this claim is unfounded. The 1893 agreement itself contains no language, clause, or time limit suggesting it was temporary or a lease. In fact, its reference to Amir’s successors implies permanence.

Furthermore, the border was reaffirmed in subsequent, more formal state-to-state treaties. After Afghanistan gained full independence in its foreign policy following the Third Anglo-Afghan War (1919), it signed the Treaty of Rawalpindi (1919) and the Anglo-Afghan Treaty (1921). Both treaties included articles where Afghanistan explicitly accepted the Indo-Afghan frontier as accepted by the late Amir. This later acceptance by a fully independent Afghan state is the bedrock of Pakistan’s legal claim.

What is the core legal dispute?

The legal dispute crystallized in 1947 with the partition of British India and the creation of the new dominion of Pakistan.

Pakistan’s Legal Position

Pakistan’s argument is clear, consistent, and grounded in established principles of international law. Its position is not based on a single doctrine but on a combination of customary law, specific legal succession acts, and the unique status of boundary treaties.

- Uti Possidetis Juris: (as you possess, so may you possess): This is the foundational principle. It holds that new, decolonized states inherit the pre-existing administrative boundaries they held before independence. This principle was widely adopted globally, for instance, in South America after liberation from Spain, precisely to prevent the chaos of endless irredentist wars based on redrawing borders along ethnic or historical lines. Pakistan, therefore, maintains that it legally inherited the Durand Line as its internationally recognized border, just as it and India both inherited the Radcliffe Line dividing Punjab and Bengal.

- The Law of State Succession: Pakistan’s claim is further strengthened by the Vienna Convention on Succession of States in Respect of Treaties. While neither state is a signatory to the 1978 convention, it is largely held to codify pre-existing customary international law. According to this convention, while other agreements (like trade or defense alliances) may lapse upon a state’s creation, Article 11 states that a succession of states does not affect a boundary established by a treaty. This principle is accepted as a global norm to prevent destabilizing territorial claims every time a new government or state emerges.

- Specific Legal Instruments of Partition: The transfer of power was not a legal vacuum. The Indian Independence Act of 1947, passed by the British Parliament, was the legal mechanism for partition. This act, along with supplemental orders like the Indian Independence (International Arrangements) Order 1947, explicitly provided for the new dominions of India and Pakistan to inherit the treaty obligations and rights of British India. For Pakistan, this provides a direct, unbroken legal chain of succession from British India to itself, making it the legitimate inheritor of the 1893, 1919, and 1921 treaties.

Therefore, from Pakistan’s perspective, Afghanistan’s arguments about coercion or the”personal nature of the 1893 agreement are irrelevant. The border was subsequently and repeatedly reaffirmed by a fully independent Afghan state (in 1919 and 1921) and was then legally passed to Pakistan as a successor state under the universally accepted international norms designed to ensure global stability.

Afghanistan’s Counter-Arguments

Afghanistan has never accepted this. In 1947, it cast the only vote against Pakistan’s admission to the United Nations, a diplomatic protest based entirely on the border dispute. Its legal and historical arguments are:

- Coercion: The 1893 treaty is void because Amir Abdur Rahman Khan signed it under duress (the threat of British military force). While the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties codifies that a treaty procured by force is void, this principle is generally not applied retroactively to 19th-century agreements, many of which were peace treaties signed by defeated parties.

- Personal Agreement: Some Afghans argue the 1893 agreement was a personal understanding between the Amir and the British Crown, not a state-to-state treaty, and thus did not pass to the successor state of Pakistan. The entity it was signed with, British India, ceased to exist in 1947. This claim, however, is weakened by the formal 1919 and 1921 state-to-state treaties that reaffirmed the border.

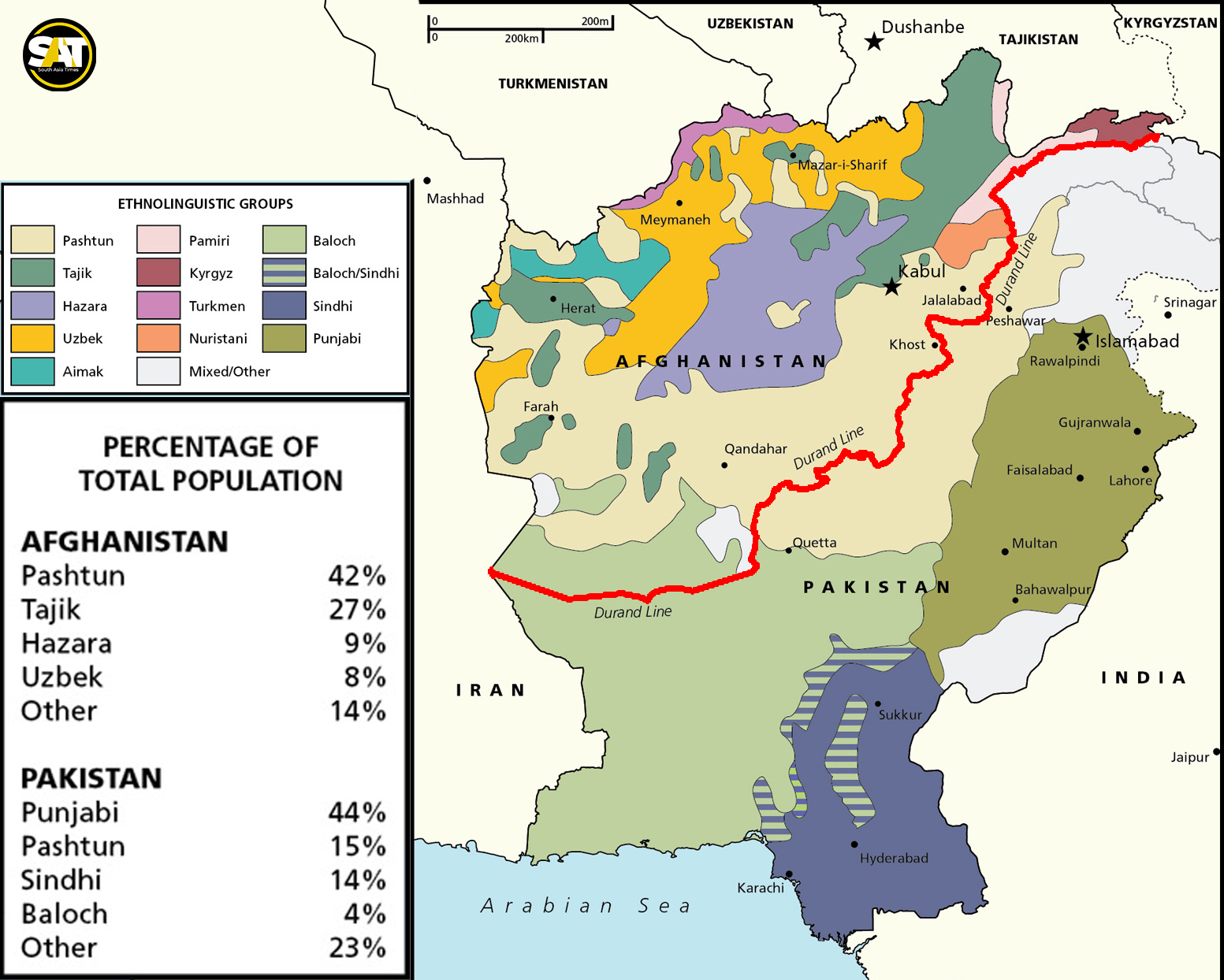

The Pashtunistan Issue

Afghanistan’s non-recognition quickly evolved from a legal argument into a potent political movement: the call for Pashtunistan. This is an ethno-nationalist project advocating for an independent state for all Pashtuns. This proposed state would be carved out of Pakistan’s territory (specifically, the provinces of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and northern Balochistan).

This movement peaked in the 1950s and again in the 1970s under Sardar Daoud Khan (who served as both Prime Minister and later President of Afghanistan). Daoud Khan actively funded and armed Pashtun insurgents inside Pakistan, leading to border skirmishes and a full-blown proxy conflict. Despite Afghanistan’s efforts, the Pashtunistan issue has never gained traction or been recognized as a legitimate grievance on any major international forum, such as the United Nations. It has remained a bilateral, regionally-contained dispute.

For Pakistan, Pashtunistan is not a border dispute, it is an existential threat aimed at the dismemberment of the country. This deeply ingrained fear has been a primary driver of Pakistan’s foreign policy toward Afghanistan for 75 years. It is the root of Pakistan’s idea that Pakistan must have a friendly government in Kabul to prevent it from actively pursuing the Pashtunistan agenda. This policy led directly to Pakistan’s interference in Afghan politics, including its support for various mujahideen factions in the 1980s.

Why is the Durand Line uniquely controversial?

The Durand Line was not the only Afghan border drawn by imperial powers. In fact, nearly all of modern Afghanistan’s borders are the product of 19th-century commissions, drawn by external powers to fix the boundaries of their buffer state.

Afghanistan’s border with modern-day Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan was demarcated by Anglo-Russian commissions. This process famously created the Wakhan Corridor, a bizarre, narrow panhandle of Afghan territory stretching to China. It was designed specifically to prevent the British and Russian Empires from having a direct border, a perfect example of an artificial, imperial-drawn line.

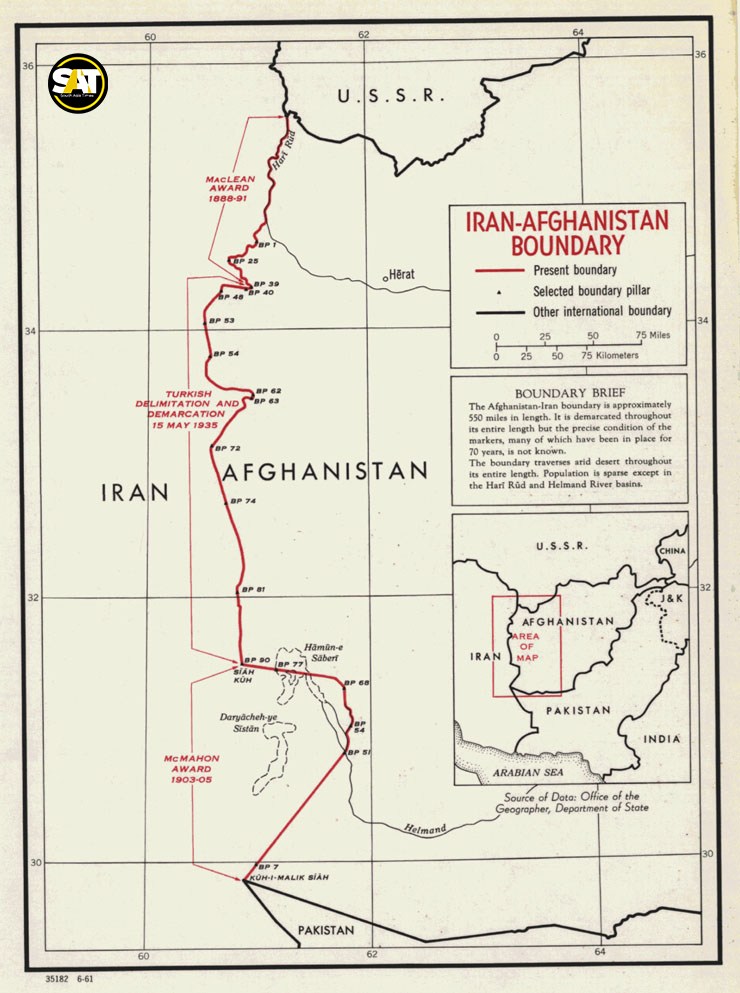

The border with Iran (then Persia) was also not settled by Afghans or Persians alone. It was defined through British arbitration (The MacMahon and McLean commissions) to settle long-standing disputes over the Sistan region.

If all of Afghanistan’s borders are colonial impositions, why do successive Afghan governments, from the monarchy to the Taliban, only contest the Durand Line?

The answer is rooted entirely in domestic ethnic politics and a cold demographic calculation. Afghan politics has historically been dominated by the Pashtun ethnic group. Pashtuns are the largest single ethnic group in Afghanistan, around 40%.

For Afghanistan’s traditionally Pashtun-led governments, contesting the Durand Line is the only border dispute that serves their domestic political interests. Successfully erasing the line and absorbing the Pashtun-majority areas of Pakistan would dramatically swell the Pashtun population within Afghanistan, cementing their ethnic dominance over other groups like Tajiks, Uzbeks, and Hazaras for the foreseeable future. This makes the “Pashtunistan” issue a powerful political tool, not just for nationalist legitimacy, but for ensuring long-term demographic control.

In sharp contrast, challenging the other imperial-drawn borders would be politically self-defeating. Contesting the northern border, for example, would mean laying claim to territories inhabited by ethnic Tajiks and Uzbeks. Incorporating more of these non-Pashtun groups into Afghanistan would dilute the Pashtun demographic dominance, weakening the very political base the leaders rely on. Therefore, the Durand Line is the only border dispute that offers a strategic demographic advantage to Afghanistan’s traditional ruling elite, ensuring its unique and persistent place in the country’s national politics.

Modern Political Significance

The stalemate over the Durand Line is intractable. Pakistan asserts its legal sovereignty based on inherited treaties and international law. Afghanistan rejects it based on ethno-nationalist ideology.

The dispute endures because it remains a potent political tool. For any government in Kabul, rejecting the Durand Line is a reliable way to generate nationalist support. It can be used to divert public attention from internal divisions, economic failures, or governance crises. By positioning themselves as defenders of Afghan territory and Pashtun unity, leaders attempt to bolster their own fragile domestic legitimacy.

This has created a modern paradox, especially with the Taliban’s return to power in 2021. The Taliban, a Pashtun-dominated religious group seeking domestic legitimacy as Afghan nationalists, have also refused to recognize the line, with many of its top leaders refusing the legitimacy of the border.

This has led to direct conflict. Pakistan holds the Afghan Taliban accountable for sheltering the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) , a group that uses the Afghan territory in the border region to launch attacks inside Pakistan. This is the modern, violent manifestation of the unresolved dispute. This ensures that the dispute will remain a central, defining, and destabilizing feature of regional politics for the foreseeable future.

This backgrounder has been produced by the SAT Research Desk.