The period following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States marked a profound inflection point in Pakistan’s security and political landscape. Under the administration of General Pervez Musharraf, Pakistan made a strategic decision to align with the US-led War on Terror. This decision, driven by global and regional geopolitical imperatives, positioned Pakistan as a key partner in counter-terrorism efforts, a role that had severe internal consequences.

The roots of this period’s security challenges, however, predate 2001, tracing back to the Soviet-Afghan War in the 1980s, Global disengagement and the subsequent Afghan civil war in the 1990s. These conflicts created a breeding ground for militancy and entrenched various extremist groups within the region, setting the stage for the wave of terrorism that would later erupt domestically.

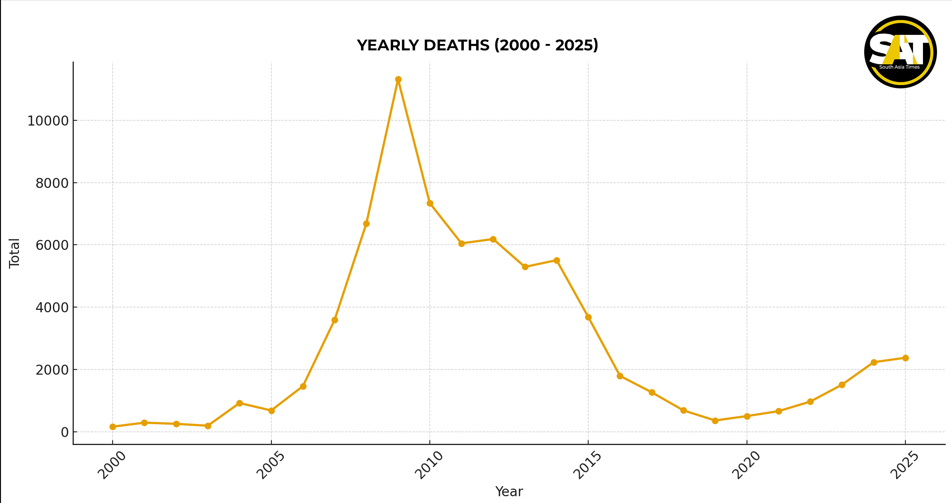

The number of terrorist incidents and fatalities in Pakistan after 2001 has shown a clear cyclical pattern, with a significant peak around 2009, a sharp decline after 2014, and a pronounced resurgence from 2021 onwards.

Phase 1: Rise of Domestic Insurgency (2001–2007)

Following the US invasion of Afghanistan in late 2001, a mass migration of Al-Qaeda and Afghan Taliban fighters occurred as they fled across the porous border into Pakistan. This influx of battle-hardened foreign fighters sought refuge in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), a semi-autonomous region that had historically been loosely governed. This new and concentrated militant presence fundamentally altered Pakistan’s security dynamics, transforming an external conflict into a significant internal threat. The government faced the complex challenge of managing its global commitments while simultaneously dealing with local groups and tribes that were providing sanctuary to foreign fighters.

In response to international pressure and the growing internal threat, Pakistan’s military launched its first major counter-terrorism operations in FATA. These included Operation al-Mizan in 2004 and the Battle of Wana in March 2004, which aimed to hunt down Al-Qaeda fighters, including the notorious Uzbek warlord, Tahir Yaldosh. These initial military actions were tactical and often resulted in short-lived peace agreements with local militant commanders, such as the Waziristan Accord in 2006. However, these limited, kinetic efforts were not comprehensive enough to dismantle the growing militant networks or address the underlying local grievances.

A pivotal development in this phase was the formal establishment of the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) in 2007. This new umbrella organization unified various militant groups under a single banner. The TTP’s formation marked a critical turning point as the insurgency shifted from being a collection of disparate groups and a byproduct of the Afghan war to a direct, domestically-focused threat against the Pakistani state itself.

This new, unified threat found its rallying cry in the July 2007 Lal Masjid Siege in Islamabad. The bloody military assault on the Red Mosque was viewed by the TTP as an attack on the House of Allah and a blatant act of submission to Western powers. In a chain of events that transformed a localized insurgency into a national threat, the TTP’s leadership declared the Pakistan Army an enemy of Islam and launched a nationwide campaign of suicide bombings. The impact was immediate and dramatic. The number of suicide attacks in Pakistan jumped from just 10 in 2006 to 61 in 2007, marking a sharp escalation in the conflict’s lethality and geographical scope. The insurgency spread from the Pak-Afghan border region to mainland Pakistan, marked by a series of suicide attacks in Lahore, Islamabad, Karachi, and Peshawar.

Phase 2: The Peak of Insurgency (2008–2014)

The period between 2008 and 2014 represents the apex of terrorist violence in Pakistan. The TTP, now a formidable and coherent force, launched a wave of mass-casualty attacks on security forces and civilian targets across the country, with terrorism-related fatalities peaking in 2009. This period was characterized by a high volume of lethal attacks, demonstrating the TTP’s expanding operational capabilities and its willingness to target major urban centers in addition to its strongholds in FATA.

In response to this escalating violence, the Pakistani military transitioned from limited raids to large-scale, multi-front campaigns. Notable operations included Operation Rah-e-Rast in Swat Valley in 2009 and Operation Rah-e-Nijat in South Waziristan.The Battle of Peochar was a key sub-operation of Operation Rah-e-Rast, where Pakistani SSG commandos were inserted by helicopters into a TTP rear-support base to conduct search-and-destroy operations . These major military offensives aimed to reclaim state authority over areas that had fallen under militant control, and they were successful in disrupting many of the TTP’s command and control structures. This period also saw many successful targetings of TTP leaders, with Baitullah Mehsud, the ameer of TTP, getting killed in 2009 and his successor, Hakeemullah Mehsud, getting killed in 2013.

Despite these military gains, the violence reached a tragic climax in December 2014 with the Peshawar Army Public School attack. In what was the deadliest terrorist attack in Pakistan’s history, the TTP killed nearly 150 people, most of whom were schoolchildren. This event was a national trauma that forced a fundamental reassessment of the government’s approach to counter-terrorism. The sheer scale and brutality of the attack shattered any remaining public ambiguity about the nature of the domestic threat.

The public outcry and national mourning that followed the school attack directly influenced a significant paradigm shift in Pakistan’s counter-terrorism strategy. This shift was politically unavoidable, as previous attempts at negotiation with the TTP had been discredited months earlier by the militants’ attack on the Karachi international airport in June 2014. The catastrophic Peshawar attack made any further dialogue politically and socially impossible.

Phase 3: Major Military Offensives and a Period of Decline (2014–2021)

In the immediate aftermath of the Peshawar school attack, Pakistan implemented a decisive and multi-pronged counter-terrorism strategy. The government launched Operation Zarb-e-Azb in June 2014, a comprehensive military offensive against militant strongholds in North Waziristan. This kinetic operation was accompanied by the formulation of a comprehensive National Action Plan (NAP), aimed at combating terrorism and extremist ideology across the country. This new approach, which also involved the lifting of a death penalty moratorium, was followed by Operation Radd-ul-Fasaad in 2017, a nationwide effort to eliminate remaining militant networks.

These large-scale military and policy initiatives led to a sharp and demonstrable decline in terrorist violence across Pakistan. The number of terrorist attacks and fatalities showed a clear downward trend between 2015 and 2019. Data shows that terrorist activity declined by 89% in 2017 since its peak in 2009. This period marked a significant success for Pakistan’s counter-terrorism efforts, bringing a degree of stability not seen in years.

During this period, Pakistan’s military operations made significant strides against TTP, pushing it across the border into Afghanistan where they sought refuge. Afghanistan has remained their primary base of operations ever since. The military’s efforts in places like the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) were largely successful in disrupting the militants’ ability to operate openly within Pakistan.

Despite these successes, militant groups proved resilient and adapted their methods. While their networks inside Pakistan were significantly weakened, they continued to pose a threat by launching attacks from their safe havens in Afghanistan. These attacks, such as the Lahore park bombing in March 2016 and the Quetta hospital bombing in August 2016, highlighted the persistent challenge posed by cross-border terrorism. Furthermore, new threats emerged during this time, including the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA), which began targeting Chinese interests, and the emergence of ISIS-K in the region. These new groups and a shift in tactics from existing ones meant that Pakistan had to remain vigilant and adapt its counterterrorism strategy to address an evolving threat landscape.

Phase 4: The Resurgence and Ongoing Conflict (2021–Present)

The withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan and the subsequent return to power of the Afghan Taliban in August 2021 proved to be a critical inflection point for Pakistan’s internal security. Some elements in the new Afghan regime provided sanctuary for TTP’s leadership and militants. Furthermore, the Afghan Taliban released a large number of TTP fighters from Afghan prisons, providing a significant boost to the group’s operational strength.

This dramatic geopolitical shift triggered a measurable resurgence of terrorism inside Pakistan. In a clear ripple effect of regional instability, the TTP, reinvigorated by a safe haven and access to US made weapons acquired in Afghanistan, launched a new wave of attacks.

Data shows a significant increase in monthly TTP attacks, from an average of 14.5 in 2020 to 45.8 in 2022. The Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) also saw a dramatic increase in its lethality, making it the fastest-growing terrorist group in the world at the time. This chain of events demonstrates that Pakistan’s internal security is inextricably linked to the political stability of its western neighbor, and a change in the political landscape in Afghanistan can directly and immediately translate into a surge in terrorism within Pakistan’s borders.

A new and influential factor in the conflict is the increasing targeting of Chinese nationals and interests in Pakistan. The March 2024 suicide bombing killed five Chinese nationals near the Dasu hydropower project. These increasing attacks led to the launching of Operation Azm-e-Istehkam in June 2024.

The Rise of Ethno-Nationalist Terrorism: The Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA)

Alongside the TTP, the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) has emerged as a significant and increasingly lethal threat, particularly in the post-2021 security environment. The BLA is an armed separatist group founded around the year 2000, succeeding an organization of a similar name formed in the 1960s with Soviet backing. Its core ideology is ethno-nationalist rather than religious. The group’s primary objective is to establish an independent Baloch state that would encompass parts of Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iran.

In addition to Pakistani security forces and officials, the BLA has targeted non-Baloch workers and settlers, particularly Punjabis, whom they consider outsiders. In 2009, a BLA leader called for Balochis to kill non-Balochis living in the province, which resulted in about 500 deaths. In 2010, the BLA claimed responsibility for the murder of a female assistant professor in Quetta, reportedly because she was Punjabi and refused to leave the province.

The BLA’s tactics have included guerrilla warfare, improvised explosive device (IED) attacks, assassinations, and suicide bombings carried out by its special Majeed Brigade, which includes both male and female operatives. A major focus of the group has been to disrupt the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). BLA attacks targeting Chinese interests, such as the 2019 attack on the Chinese consulate in Karachi have become a recurring feature of the insurgency. BLA is considered a terrorist organization by Pakistan, China, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the European Union.

The Human and Economic Toll of Terrorism

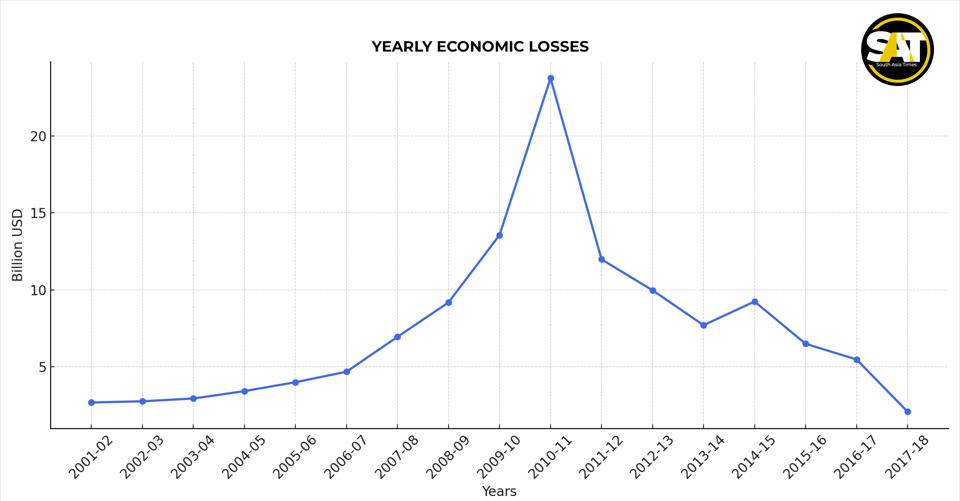

The human and economic toll of terrorism on Pakistan has been staggering, representing a profound and enduring burden on the nation.17 The conflict has claimed tens of thousands of lives and caused massive financial losses, impacting every sector of the economy.17

A quantitative analysis of the human cost reveals the scale of the tragedy. By a conservative estimate, approximately 35,600 Pakistanis were killed and more than 40,000 were injured from 2004 to 2010. Other estimates suggest that between 80,000 and 100,000 people, including terrorists, have died in Pakistan since 2001.

Beyond the human toll, the economic impact of terrorism has been immense, affecting both direct and indirect costs. The direct and indirect economic costs of terrorism from 2000 to 2010 were estimated at 68 billion Dollars by the Government of Pakistan. This figure rose to a cumulative loss of 150 billion Dollars by 2025.

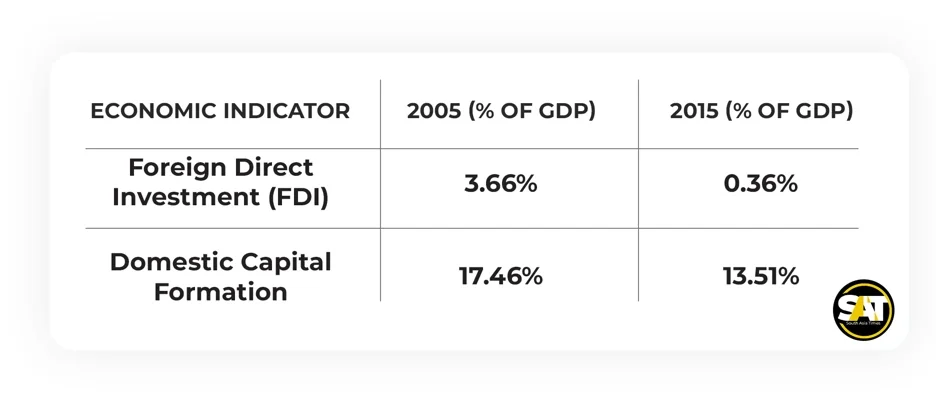

The secondary or indirect costs of terrorism are equally profound and have had a lasting impact on Pakistan’s economic stability. Terrorism has an inverse relationship with key economic indicators. Terrorism significantly harmed Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and domestic capital formation. For example, the net inflow of FDI decreased dramatically from 3.66% of GDP in 2005 to just 0.36% of GDP in 2015. Similarly, domestic capital formation dropped from 17.46% to 13.51% of GDP during the same period.

This is because terrorism elevates the costs of business, including higher security measures and insurance premiums, which in turn reduces returns on investment and deters both foreign and domestic capital. The following table demonstrates this inverse relationship.

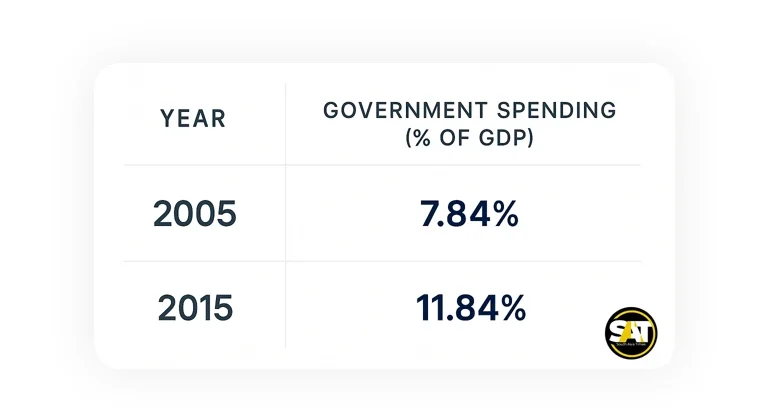

Furthermore, the government’s response to terrorism has also incurred significant economic costs. The need to increase security measures has resulted in a phenomenon known as crowding-in government expenditures. Government spending increased from 7.84% of GDP in 2005 to 11.84% of GDP in 2015, as resources were diverted to security-related expenses, thereby reducing funds available for other critical sectors and hindering overall economic growth. This is visually represented in the table below.

A Persistent Threat

Since 2001, Pakistan’s struggle with terrorism has been a cyclical conflict, defined by distinct phases of escalation, containment, and resurgence. The conflict began as a result of regional geopolitical shifts, specifically the post-9/11 US invasion of Afghanistan, which pushed militant groups into Pakistan’s FATA region. The conflict peaked in the late 2000s and early 2010s, culminating in the horrific Peshawar school attack in 2014, a tragic event that forced a fundamental paradigm shift in Pakistan’s counter-terrorism strategy.

This strategic pivot, marked by major military operations like Zarb-e-Azb and the National Action Plan, led to a period of significant decline in terrorist violence. However, this period of containment proved temporary. The withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan and the subsequent return of the Afghan Taliban to power in 2021 provided a safe haven and operational boost to the TTP, directly leading to a new and ongoing resurgence of terrorism inside Pakistan. This demonstrates that Pakistan’s internal security is inextricably linked to the stability of its western neighbor and the broader geopolitical landscape.

This backgrounder has been produced by the SAT Research Desk.