The protracted presence of Afghan refugees in Pakistan represents one of the world’s most enduring and complex humanitarian crises, spanning over four decades. Pakistan has hosted millions of displaced Afghans, evolving from an urgent humanitarian response to a deeply entrenched socio-economic and geopolitical challenge. This sustained presence has transformed from a temporary emergency to a long-term demographic shift, with successive generations living in refugee camps and integrating into the local society.

For over forty years, Afghans have fled violence and instability, making them one of the world’s largest protracted refugee populations. The crisis, initially triggered by domestic upheavals and the Soviet invasion in 1979, was the largest operation for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in the 1980s. Pakistan has borne a “gargantuan task” of administering relief for millions. At its peak, Pakistan hosted over five million Afghan refugees, with estimates suggesting nearly 4.5 million undocumented Afghans by 1990. Currently, Pakistan continues to host approximately 1.55 million registered Afghan refugees and asylum-seekers, alongside over 1.3 million Afghans of varying legal statuses.

Major Waves of Influx

The influx of Afghan refugees into Pakistan is intrinsically linked to a series of protracted conflicts and geopolitical shifts in Afghanistan.

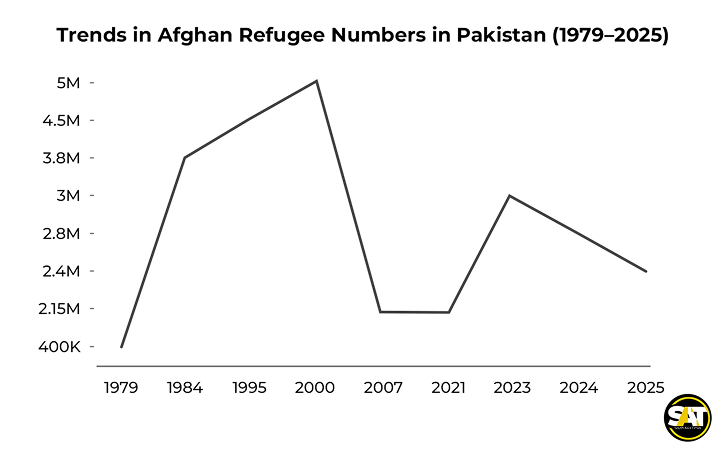

The initial significant wave began in the late 1970s, with over 400,000 people fleeing violence into Pakistan. Numbers dramatically swelled following the Soviet invasion in 1979, reaching over four million in Pakistan by late 1980, and exceeding five million in Pakistan and Iran by 1984. Afghans received “prima facie” refugee status in Pakistan, a policy allowing a massive, prolonged presence without formal national refugee law. The Soviet invasion triggered vast external intervention, with the USA and allies, notably Pakistan, providing significant support.

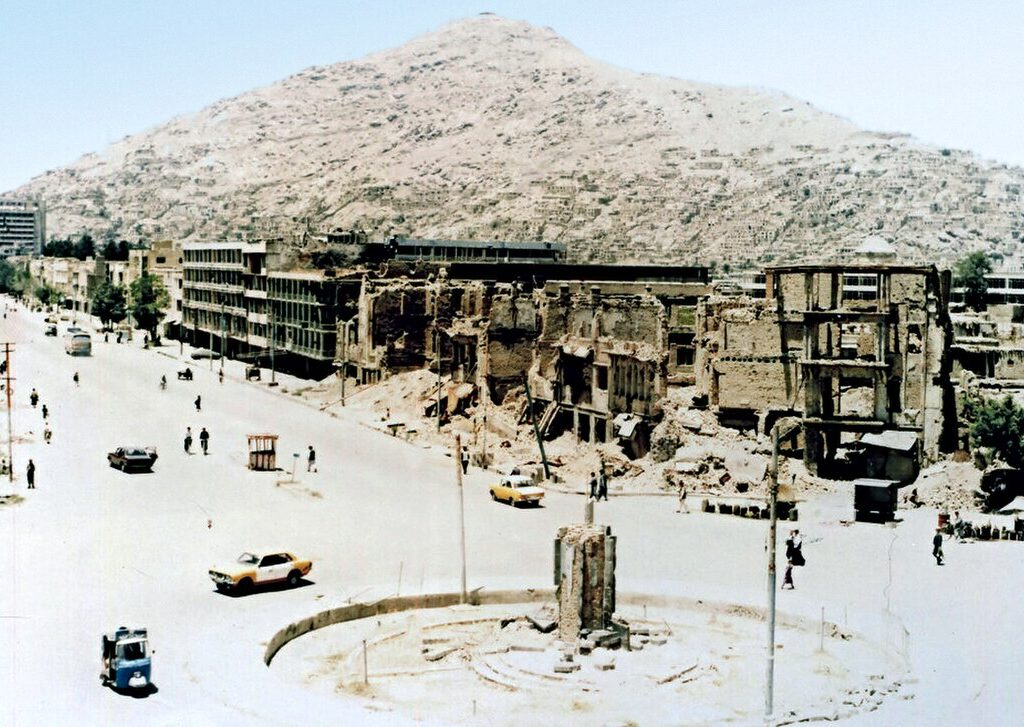

Even after the Soviet withdrawal in 1988-89, the devastating civil war between different factions led to devastation of large sections of Kabul city and a new refugee exodus towards Pakistan.

The US-led intervention in 2001 sparked another significant wave, but this decade also saw the return of a sizable number of Afghan refugees, bringing Afghan refugee numbers in Pakistan to its lowest since the 1980s.

The most recent influx, an estimated 600,000 Afghans, occurred after the Taliban takeover, with many women and girls seeking refuge from severe gender-based restrictions and loyalists of the previous regime fearing retribution.

Demographics

Understanding the scale and composition of the Afghan population in Pakistan is crucial. Figures have fluctuated significantly, with a complex interplay of registered and unregistered individuals.

Initial influxes saw numbers rise from 400,000 to over four million by 1980, reaching over five million in Pakistan and Iran by 1984. By 1990, an estimated 4.5 million undocumented Afghans resided in Pakistan. Since 2002, UNHCR has facilitated the repatriation of over 4.38 million Afghan refugees from Pakistan.

As of July 2025, Pakistan hosts approximately 1.5 million registered Afghan refugees and asylum-seekers, plus over 1.2 million Afghans of different legal statuses.UNHCR’s 2024 data indicated around 2.6 million Afghans: 1.34 million registered refugees, and remaining of various legal statuses.

Afghan populations are primarily based in urban areas, with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa hosting the largest share (52.6%), followed by Balochistan (24.0%), Punjab (14.3%), Sindh (5.5%), and Islamabad (3.2%). A 2002 study by UNHCR and the Government of Pakistan revealed that 81% of Afghan refugees in Pakistan were ethnic Pashtuns, followed by 7.3% Tajiks and 2.3% Uzbeks.

The substantial number of Afghans born and raised in Pakistan over four decades who are denied citizenship creates a generational statelessness issue. Despite the Pakistan’s Nationality Act entitling those born in Pakistan to citizenship, this right has been denied on the grounds that their parents were refugees.

Legal Framework

Pakistan’s legal and policy approach to Afghan refugees is characterized by its unique position as a non-signatory to international refugee conventions, leading to reliance on administrative measures and bilateral agreements.

Pakistan is not a party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees or its 1967 Protocol. Consequently, it lacks national refugee legislation and formal procedures for determining refugee status. This means Pakistan manages refugee crises through international cooperation and ad-hoc policies, rather than a codified legal framework.

In 2007, Pakistan issued Proof of Registration cards (POR), granting temporary legal stay, freedom of movement, and exemption from the Foreigners Act,1946. The Afghan Citizen Card (ACC) is issued to legal migrants. However, these cards provide only “temporary legal status and limited access to services,” while Undocumented Afghan Refugees” lack legal status and are vulnerable to deportation.

Cooperation between the Government of Pakistan (GoP) has been close since the crisis’s early days. Key agreements include a 1988 bilateral agreement formalizing refugee presence, a 1993 Tripartite Agreement for organized return, and a 2001 agreement ending prima facie status for new arrivals (though not fully enforced). A 2003 Tripartite Agreement aimed to register and count Afghan refugees and plan repatriation, followed by a 2006 Census Agreement.

Phases of Pakistan’s Policy Responses and Repatriation Efforts

Pakistan’s policy towards Afghan refugees has shifted from an initial open-door approach to increasingly coercive repatriation drives, influenced by domestic security and bilateral relations.

Following the 1979 Soviet invasion, Pakistan granted “prima facie” refugee status, a humanitarian and strategic welcome underpinned by Cold War geopolitics.

Over decades, Pakistan’s stance hardened. PoR card extensions have been reluctant and arbitrary. This intensified after the December 2014 Peshawar school massacre, leading to crackdowns and returns. In 2016, up to 365,000 refugees were forcibly returned to Afghanistan from Pakistan.

Islamabad’s response is often shaped by relations with Kabul. The latest crackdown, beginning in late 2023, was justified by increasing crime and militancy, with officials citing Afghan nationals in suicide bombings.

In October 2023, Pakistan announced a plan to deport foreign nationals without valid visas, primarily affecting undocumented Afghans. Since the start of the operation, tens of thousands of Afghans have been deported.

Foreign Aid and International Contributions

International assistance has played a crucial, albeit fluctuating, role in supporting Afghan refugees in Pakistan and facilitating their return, mirroring geopolitical shifts.

The Soviet Invasion Era (1979-1989)

A Surge in Cold War-Driven Aid During the initial massive influx after the 1979 Soviet invasion, international aid to Pakistan surged. The United States and its allies, provided substantial financial assistance and weapons, often channeled through humanitarian aid organizations, to support the Afghan resistance (mujahideen) and the millions of refugees in Pakistan. This assistance was deeply intertwined with the political goals of donors, serving as a tool in the proxy conflict between the US and Soviet empire. Pakistan, as a frontline state, received economic and geopolitical assistance in exchange for its role in hosting refugees and supporting the resistance.

Post-2001 Period: The War on Terror and Development Aid

Following the U.S. intervention in Afghanistan in 2001, international humanitarian aid continued, often within the Global War on Terror framework. Since 2002, the USA has provided over $273 million in aid for Afghan refugees in Pakistan and their host communities, including nearly $60 million in Fiscal Year 2022. In 2015, the U.S. government also programmed over $88 million for assistance across Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran, contributing an additional $22 million to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and ICRC.

In 2002, the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM) provided $67.3 million to UNHCR and $7.8 million to the International Organization for Migration (IOM) to help over 2 million Afghan refugees return home, with 1.8 million returning from Pakistan. The State Department/PRM also gave UNICEF $2.0 million for a “back to school” program. However, this assistance followed a period of fluctuations. By late 1995, UNHCR and the World Food Programme (WFP) had ended food aid to most Pakistani refugee camps due to huge funding shortfalls, which led to Pakistani authorities feeling abandoned by the international community after the Soviet withdrawal.

Global Funding Gaps vs Pakistan’s Economic Strain

Overall, international contributions have seen periods of high engagement, particularly during the Cold War and the initial phase of the post-9/11 intervention, followed by significant declines and persistent funding shortfalls in more recent years, especially after the Soviet withdrawal and the Taliban’s return to power in 2021. This fluctuating commitment has placed a disproportionate and often uncompensated burden on Pakistan as the primary host nation.

While international aid has been provided, Pakistan has also incurred significant costs. The direct and indirect cost incurred by Pakistan due to incidents of terrorism, which some Pakistani officials link to the refugee presence, amounted to US$106.98 billion over a 14-year period up to 2014-15. The presence of millions of refugees has also placed a heavy burden on Pakistan’s resources. When the economic burden and losses from terrorism are compared to the total support Pakistan received, a disproportionately steep loss for Pakistan becomes evident.

Impacts on Pakistan

The prolonged presence of millions of Afghan refugees has profoundly shaped Pakistan’s economic, political, and social landscape, presenting a complex interplay of challenges and, in some areas, positive contributions.

Economic Impacts: The most immediate consequence has been a heavy burden on Pakistan’s resources, straining essential services like food, housing, water, sanitation, and transportation. A large population also contributes to inflation, as increased demand drives up prices, potentially causing resentment. The impact on Pakistan’s labor market has been mixed. Refugees have contributed to the informal economy by starting businesses in construction, retail, and transportation, boosting economic activity. The influx of Afghan livestock also boosted local markets, and foreign-funded projects supported infrastructure. However, friction over employment exists. Low-skilled refugees expand the labor supply for unskilled occupations, suppressing wages and increasing unemployment for native workers, especially in the informal sector. Unemployment concerns are acute in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Some Afghan traders have reportedly become wealthy without paying taxes, impacting revenue collection. Overall, empirical results indicate a negative impact on Pakistan’s economic growth in both the short and long run, suggesting refugee influx lowers real economic activity. Refugee influxes have also created environmental problems through overexploitation of natural resources.

Political Impacts: The presence of Afghan refugees has been linked to increased internal security threats and political instability, including sectarian violence, drug trafficking, terrorism, and organized crime. Pakistani authorities often blame Afghans for criminal and terrorist acts, and many Afghan refugees and citizens have been found involved in various suicide attacks and other crimes. This has fueled anti-Afghan sentiment and discrimination.

Social Impacts: The influx of Afghan refugees into Pakistan has had both challenging and positive social impacts. Competition over resources like land, employment, and water has led to friction, and some local populations have expressed concerns about demographic imbalance. Host attitudes have, in some cases, turned negative, resulting in intimidation and discrimination, particularly in schools. Public services such as healthcare and education are also significantly strained, with crowded classrooms and limited access for refugees. Cultural and social integration can be difficult, with many refugees experiencing cultural shock, language barriers, and a lack of documentation, which exposes them to exploitation.

Despite these challenges, there have been positive social contributions. Many refugees have become integrated into Pakistani society, contributing to the local culture and workforce. Shared ethnic, linguistic, and religious ties, especially among Pashtuns, have facilitated assimilation and minimized cultural friction in border provinces. Intermarriage has also helped to strengthen social bonds.

Pakistan’s Decision to Return Refugees

Pakistan’s decision to implement mass deportations of Afghan refugees, particularly since late 2023, is a complex policy choice driven by security concerns, domestic pressures, and geopolitical considerations. The government of Pakistan officially cited increasing crime and violence, including suicide attacks, as the primary motivation for its actions. In 2023 Pakistani officials claimed 14 of 24 suicide bombings since January were carried out by Afghan nationals, attributing this to the Afghan Taliban providing safe harbor to militant groups. In October 2023, a high-level meeting announced an October 31 deadline for illegal foreign nationals to leave voluntarily or face deportation.

However, outside observers note significant political motivations behind the policy. The Pakistan Army may have hoped to pressure the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan into a more cooperative foreign policy regarding cross-border militancy.

The implementation process has been widespread and coercive. These forced returns have raised significant human rights concerns. Human Rights Watch and the UN Refugee Agency have documented that Pakistan’s coerced returns and deportations may violate international obligations, including the principle of non-refoulement, which prohibits forced return to a place where individuals face a genuine risk of persecution or irreparable harm. The UNHCR is particularly concerned for women and girls forced to return to Afghanistan, where their human rights are severely at risk under Taliban rule. The large-scale, hasty returns also pressure basic services and livelihoods in Afghanistan, worsening an already dire humanitarian crisis and risking regional instability.

The Return Journey

The return of Afghan refugees from Pakistan is creating a tough situation. Many returnees, especially the young people who have never lived there, are going back to a country with ongoing conflict, violence, and a struggling economy. They often lack social ties and face extreme poverty.

Reintegrating into Afghan society is proving difficult. Returnees struggle to find jobs, and the healthcare system is in crisis. Women, girls, journalists, and former government workers are at particular risk, facing a loss of rights and potential reprisals. On top of all this, many people are dealing with trauma.

While some organizations, like the UNHCR and IOM, are providing cash grants and humanitarian aid, these programs often focus on immediate needs rather than long-term solutions. They also face issues with limited resources and flawed beneficiary selection, making it hard to provide the comprehensive support that returnees desperately need. To break this cycle, coordinated policies are essential, combining sustainable livelihoods, education, healthcare, and legal protections for returnees. Without such a strategic approach, repatriation risks deepening instability in Afghanistan and the wider region.

This backgrounder has been produced by the SAT Research Desk.