Summary

-

- The roots of the conflict lie in the creation of the state of Israel in 1948 on historic Palestinian land, an event that led to a war and the displacement of over 750,000 Palestinians. The 1967 war further entrenched the conflict by beginning Israel’s military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza.

-

- While many Arab states have normalized relations with Israel since 1973, a resolution for Palestinian statehood remains elusive.

-

- Major peace frameworks, including the Oslo Accords, failed to halt the growth of Israeli settlements, which is as a primary obstacle to a viable two-state solution.

-

- The repeated collapse of high-stakes negotiations has often been a catalyst for widespread Palestinian uprisings, including the First and Second Intifadas.

-

- Successive Israeli governments have consistently rejected terms that would grant a Palestinian state full sovereignty, including control over its borders, airspace, and resources.

The Pre-1973 Context: From Nakba to Occupation

The modern Israeli-Palestinian conflict began with the creation of Israel in 1948 and the subsequent Arab-Israeli War. For Israelis, it was their War of Independence, for Palestinians, it was the Nakba, or “catastrophe,” which resulted in the displacement of over 750,000 Palestinians and the destruction of hundreds of their villages. The war concluded with armistice agreements but no permanent peace, leaving the newly established State of Israel in control of 78 percent of historic Palestine. The remaining 22 percent, the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and the Gaza Strip, fell under Jordanian and Egyptian control, respectively.

The geopolitical landscape was radically altered by the June 1967 Six-Day War. In a swift military victory, Israel captured the West Bank, Gaza, Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, and Syria’s Golan Heights, placing over a million Palestinians under military occupation. In response, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 242, which established the land for peace formula that would become the bedrock of future diplomacy.

However, the Arab world, meeting in Sudan, issued the Khartoum Resolution, famously known for its Three No’s:

1) No peace with Israel.

2) No recognition of Israel.

3) No negotiations with Israel.

This policy of total confrontation defined the period leading up to 1973. The era was characterized by a state of perpetual conflict, with the PLO, established in 1964, conducting armed operations against Israel, and Israel consolidating its military rule over the occupied territories.

The 1973 Yom Kippur War began with a surprise coordinated attack by Egypt and Syria, which inflicted heavy losses on the Israeli military in its initial days. Although Israel eventually repelled the assault and won a military victory, the war shattered the nation’s sense of invincibility that had prevailed since 1967. The high cost in lives and the initial military setbacks forced a profound strategic reassessment within Israel. This forced a strategic reassessment on all sides and opened the door, for the first time, to direct diplomacy.

Camp David Accords (1978)

The first major post-1973 peace initiative, the Camp David Accords of 1978, successfully established peace between Israel and Egypt. Brokered by US President Jimmy Carter, the accords proposed a five-year transitional period of full autonomy for Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza, to be followed by negotiations on the final status of the territories.

The plan ultimately failed due to conflicting interpretations of autonomy. The Israeli government, led by Prime Minister Menachem Begin, viewed it as a form of limited administrative self-rule, not as a step toward sovereignty. Israel insisted on retaining control over land, water, and airspace and continued to build settlements in the occupied territories. The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was not invited to the talks and rejected the accords, seeing them as a separate peace that legitimized continued Israeli control and failed to address core Palestinian national aspirations, such as the right of return for refugees. Egypt’s move marked the first major crack in the unified Arab front of no recognition, but the rest of the Arab world and the PLO remained committed to their rejectionist stance.

Oslo Accords (1993-95)

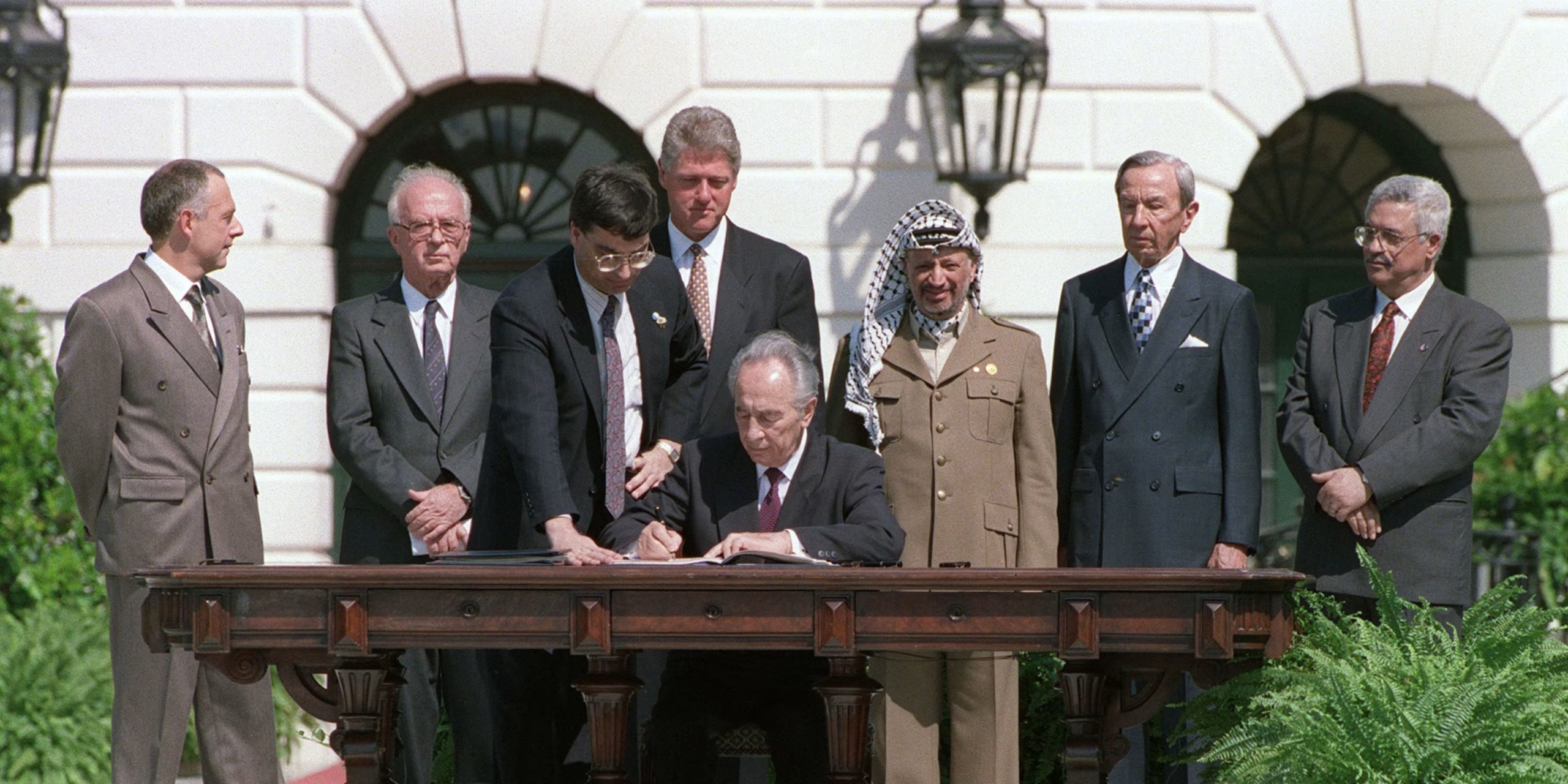

No, but they created a pathway for that possibility. Following the First Intifada, the 1991 Madrid Conference and subsequent secret negotiations produced the 1993 Oslo Accords. The accords established the Palestinian Authority (PA) and set a five-year timeline for negotiations on final status issues. This moment marked a monumental shift in the Palestinian position. In letters preceding the signing, PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat officially recognized the State of Israel, accepted UN Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338, and renounced armed struggle. This was the PLO’s formal acceptance of a two-state solution, a dramatic departure from its long-held goal of liberating all of historic Palestine.

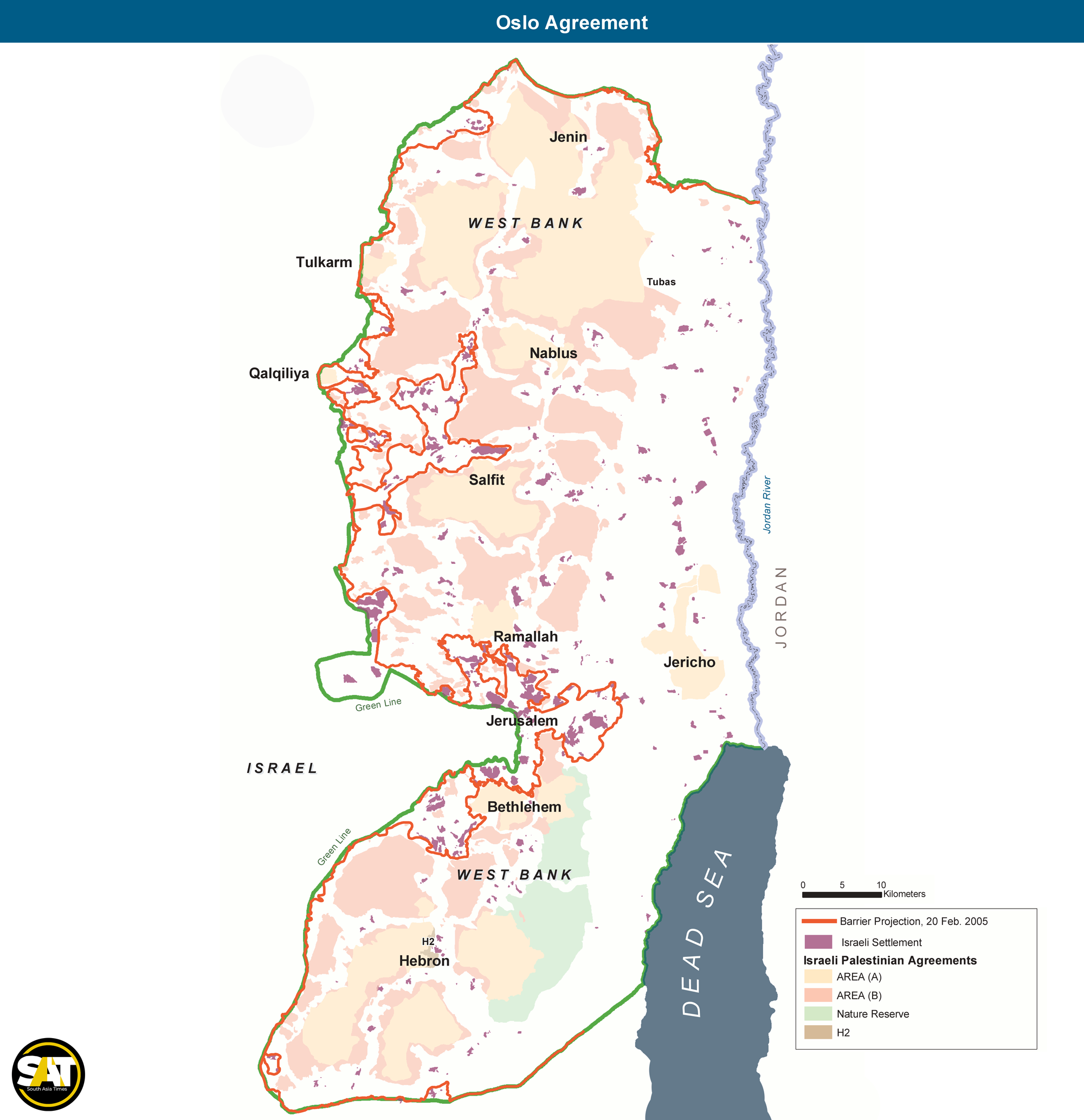

However, the accords were fundamentally flawed. The West Bank was divided into three zones:

Area A (full PA civil and security control)

Area B (PA civil control, joint Israeli-Palestinian security control)

Area C (full Israeli civil and security control).

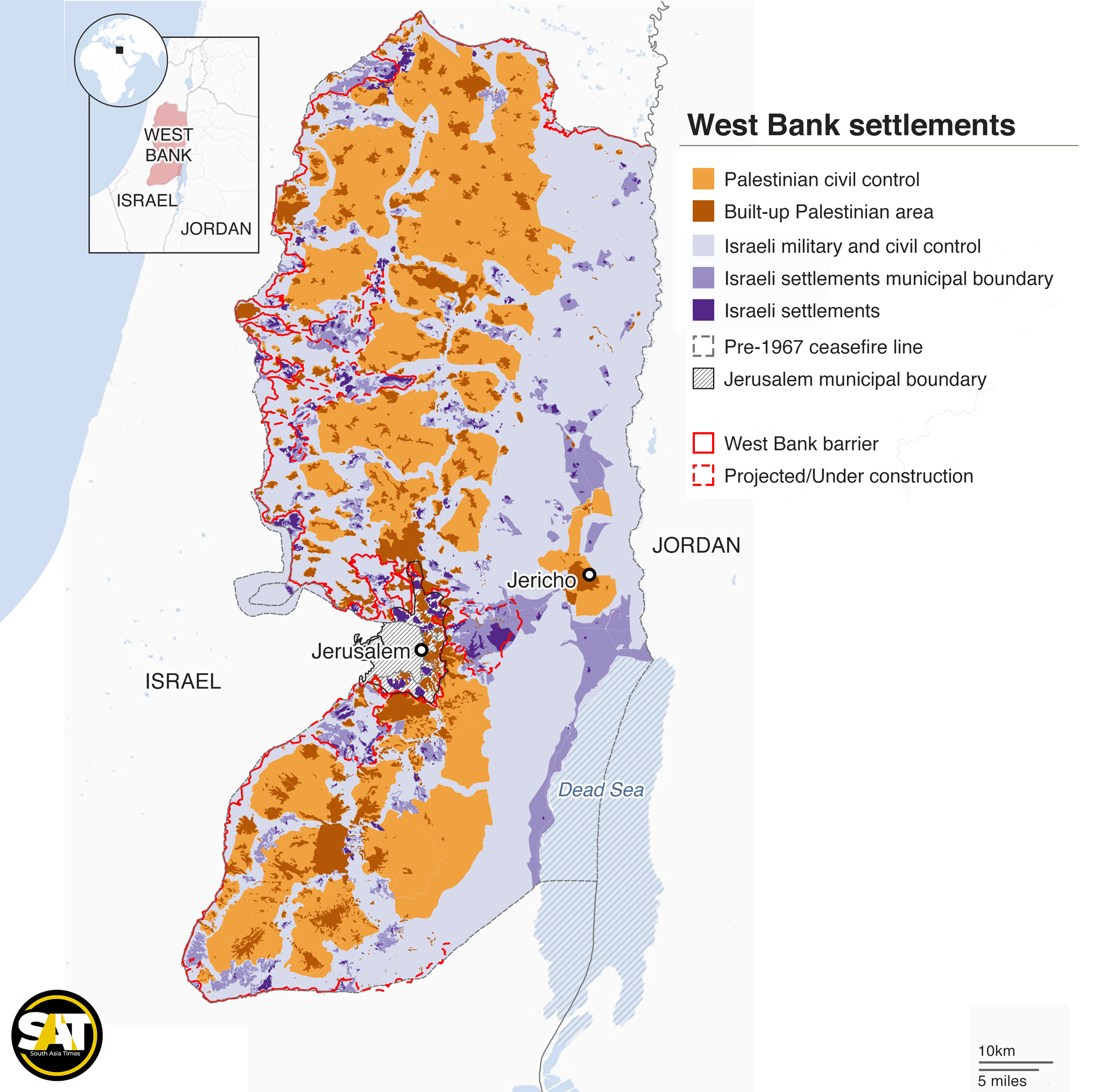

Area C, containing all Israeli settlements and constituting over 60% of the territory, was intended to be gradually transferred to PA control. This transfer never fully materialized.

The accords also did not require Israel to halt settlement expansion, which continued and even accelerated. After the assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in 1995 by a right-wing extremist, his successors were openly critical of the framework. This fragmentation of territory, coupled with settlement growth, eroded Palestinian hopes for a viable state and directly contributed to the frustrations that would later ignite the Second Intifada.

Camp David (2002)

By 2000, US President Bill Clinton convened a high-stakes summit at Camp David to broker a final deal. Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak made what was seen as an unprecedented offer: a Palestinian state on over 90% of the West Bank and all of the Gaza Strip, with a capital in East Jerusalem.

However, the offer came with conditions that fell short of full sovereignty. Israel sought to annex major settlement blocs, maintain long-term military control over the Jordan Valley, and retain authority over the proposed state’s borders and airspace. On Jerusalem, the proposal offered Palestinians sovereignty over Arab neighborhoods but kept Israeli sovereignty over the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif, a site of immense religious importance to both Muslims and Jews. It also rejected the Palestinian right of return for refugees, offering a fund for compensation instead. PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat rejected the offer. The summit’s collapse, followed by a provocative visit by Ariel Sharon to the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound, was a primary catalyst for the outbreak of the Second Intifada, a period of intense armed conflict.

Arab Peace Initiative (2002)

In 2002, the Arab world executed a complete reversal of its 1967 “Three No’s.” In the midst of the Second Intifada, the Arab League, led by Saudi Arabia, unanimously adopted the Arab Peace Initiative. This landmark proposal offered Israel full normalization of relations with the entire Arab world in exchange for:

- A full withdrawal from all territories occupied since 1967.

- The establishment of a sovereign Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital.

- A just solution to the Palestinian refugee issue based on UN Resolution 194.

This initiative represented a unified Arab consensus in favor of a two-state solution. The Israeli government under Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, however, immediately dismissed it, objecting to the call for a full withdrawal to the 1967 lines and the reference to the right of return. No Israeli government has ever accepted it as a basis for negotiations.

Decades of Diplomatic Stagnation

This period was marked by diplomatic stagnation and significant shifts in Palestinian politics. Following the death of Yasser Arafat and Israel’s unilateral disengagement from Gaza in 2005, Hamas won the 2006 Palestinian legislative elections. While its original charter called for the liberation of all of historic Palestine, since the mid-2000s the group’s leadership repeatedly signaled a pragmatic shift. Multiple Hamas leaders stated a willingness to accept a long-term truce, or hudna, and the establishment of a Palestinian state on the 1967 borders, even as they refused to formally recognize Israel. This was later codified in a 2017 policy document, marking a significant evolution from its rigid foundational position toward the international consensus on a two-state framework.

Despite this, diplomatic efforts faltered. The 2007 Annapolis Conference briefly revived talks, but they fizzled out. The most significant effort was the 2013–2014 initiative led by U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, which collapsed as Israel continued to approve new settlement construction. The subsequent decade saw a formal abandonment of negotiations in favor of managing the conflict.

Post 7th October 2023

The October 7, 2023, Hamas attack and ensuing war in Gaza renewed an international push for a long-term political solution, with multiple actors presenting comprehensive plans that were systematically rejected by Israel.

The US Framework: The Biden administration pushed for a day after plan centered on a revitalized Palestinian Authority and a time-bound, irreversible pathway to a Palestinian state, linked to normalization between Israel and Saudi Arabia. Israel scuttled this framework from the start. On January 18, 2024, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu publicly rejected the U.S. vision, stating he would not compromise on full Israeli security control over all the territory west of the Jordan River.

The Arab Plan: In early 2024, a consortium of five key Arab nations, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, Egypt, and Jordan, developed their own detailed proposal for an irreversible path to Palestinian statehood in return for normalization. Israeli officials dismissed this out of hand, with members of Netanyahu’s government labeling the idea a reward for terror.

The European Union Roadmap: In January 2024, foreign policy chief Josep Borrell presented a multi-stage roadmap that began with an international peace conference. This plan received little traction in Israel.

Israel’s rejection of this emerging international consensus was formalized on February 21, 2024, when the Israeli Knesset voted overwhelmingly (99-9) to formally oppose any “unilateral recognition” of a Palestinian state.

What are the core obstacles to peace in the region?

The history of failed negotiations points to several deeply entrenched obstacles that prevent a lasting and just peace in the region:

- Israeli Rejection of Full Palestinian Sovereignty: A consistent Israeli policy across various governments has been the refusal to grant a Palestinian state full control over its own borders, airspace, security, and resources. This position is framed by Israel as essential for its security, but it makes a genuinely independent state impossible from the Palestinian perspective.

- Unabated Settlement Expansion: The continuous growth of Israeli settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, which are illegal under international law, has created facts on the ground that fragment Palestinian territory and make a contiguous and viable state geographically difficult, if not impossible.

- The Question of Jerusalem and Refugees: The final status of Jerusalem, which both Israelis and Palestinians claim as their capital, and the right of return for Palestinian refugees displaced in 1948 and 1967, remain two of the most emotionally and politically charged issues with no compromise in sight.

The long history of failed negotiations reveals a clear pattern: peace efforts have repeatedly collapsed against Israel’s refusal to grant full Palestinian sovereignty, despite an enduring international consensus for a two-state solution. This core rejection underpins the other intractable issues of unabated settlement expansion, the status of Jerusalem, and the rights of refugees. Without a fundamental shift on this primary obstacle, the peace process appears destined to repeat the failures of its past.

This backgrounder has been produced by the SAT Research Desk.

![Prime Minister Narendra Modi with External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar at an official event. [Photo Courtesy: Praveen Jain via The Print].](https://southasiatimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/20-scaled-e1755601883425-1024x576-1-150x150.webp)